-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

PFAS Regulation and Development at the European Level with Focus on Germany and France

Publication

The CrowdStrike Incident – A Wake-Up Call for Insurers?

Publication

Decision-Making in the Age of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Publication

Buildings Made of Wood – A Challenge For Insurers?

Publication

Cat Bonds – A Threat to Traditional Reinsurance? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

Gen Re’s valuable insights and risk transfer solutions help clients improve their business results. With tailor-made reinsurance programs, clients can achieve their life & health risk management objectives.

UnderwritingTraining & Education

Publication

Fasting – A Tradition Across Civilizations

Publication

When Actuaries Meet Claims Managers – Data-Driven Disability Claims Review Business School

Business School

Publication

Chronic Pain and the Role of Insurers – A Multifactorial Perspective on Causes, Therapies and Prognosis

Publication

Simplicity, Interpretability, and Effective Variable Selection with LASSO Regression Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Autonomous Vehicles – The Murky Road Ahead for Manufacturers, Insurers and Drivers

January 27, 2020

Timothy Fletcher

English

As driverless cars continue to be programmed to avoid accidents, who might be spared in an accident - a young girl, a male executive or an elderly woman crossing the road? This is just one of the moral and technological challenges facing developers before autonomous vehicles head to entrance ramps and onto our roads.

As the new decade dawns, a world with autonomous vehicles (AVs) seems both alluring and elusive. Imagine vehicles that efficiently navigate their way between destinations, unburdened by today’s congested highways. Or motorists, after years of lengthy and frustrating commutes, able to use that time to work, relax or enjoy social media. Automobile manufacturers, formerly selling to individual buyers, would instead manage fleets that users pay on a subscription-based model. And, for the insurance industry, imagine property damage and liability claims plummeting, all due to the decrease or even absence of human drivers on the road.

While significant technological impediments remain, the gap continues to narrow in solving the problems that have kept autonomous vehicles from going mainstream. If progress continues, and we see wide use of AVs within the next 10 to 20 years, what might the world look like? In other words, how would autonomous and human-operated vehicles interact with each other as well as pedestrians and cyclists? What unforeseen risks may be looming? In what ways would AVs be programmed to minimize harm when two unpalatable crash alternatives are presented?

Current State

Five years ago, AV developers forecasted that by 2021 large numbers of self-driving vehicles would be on public roads. Several noteworthy accidents - most notably the 2018 Tempe, Arizona pedestrian death caused by a self-driving Uber vehicle - prevented that dream from coming to fruition. Nevertheless, AV development has continued at a rapid pace, with each of the major manufacturers either building outright or partnering with others to build AV development centers. Here in the U.S., some 29 states have enacted AV legislation, with Arizona, Florida and Michigan establishing themselves as leading AV proving grounds.

AV testing remains ongoing in several American cities. In late 2019, an autonomous tractor-trailer journeyed across the U.S. without incident. This month Waymo, the self-driving technology development company, announced its AVs have covered 20 million miles, up from 10 million just one year ago. However, it should be noted such testing is tightly controlled, with AVs being monitored by either an on-board “safety driver” or by human monitoring from a central command center. Future development will focus on providing the remaining 10% of technology needed to bring AVs mainstream, including the geo-mapping, sensors, algorithms and programming needed to replicate human behavior and enable responses to the innumerable variables associated with everyday driving.

The Challenges Ahead

There are myriad challenges. How, for example, does one program an AV to respond to erratic human driving behavior, such as cutting across a lane to make a turn, driving at inconsistent speeds, or road rage? Other impediments come to mind as well, such as, in what way should other drivers or a pedestrian be made aware of AVs sharing their road? Beyond the technology lies another hurdle based on public perception. How do you convince the public that AVs are safe and reliable, considering the recent Brookings Institution survey that states only 21% of Americans would choose to ride in an autonomous vehicle?

The “Trolley Problem”

No one suggests that these hurdles are insurmountable. However, another ethical and algorithmic conundrum may perplex developers, regulators, and the AV-using public for quite some time. Assume for the moment the following scenario: An AV suddenly encounters a collision directly ahead on a busy residential street and cannot stop without avoiding contact or injury. A passenger in the AV is a highly regarded neurosurgeon using her commute to prepare for an upcoming procedure. Bordering the street is a sidewalk. On the left is an elderly woman struggling with her walker. To the right are two uniformed girls walking to a nearby private school.

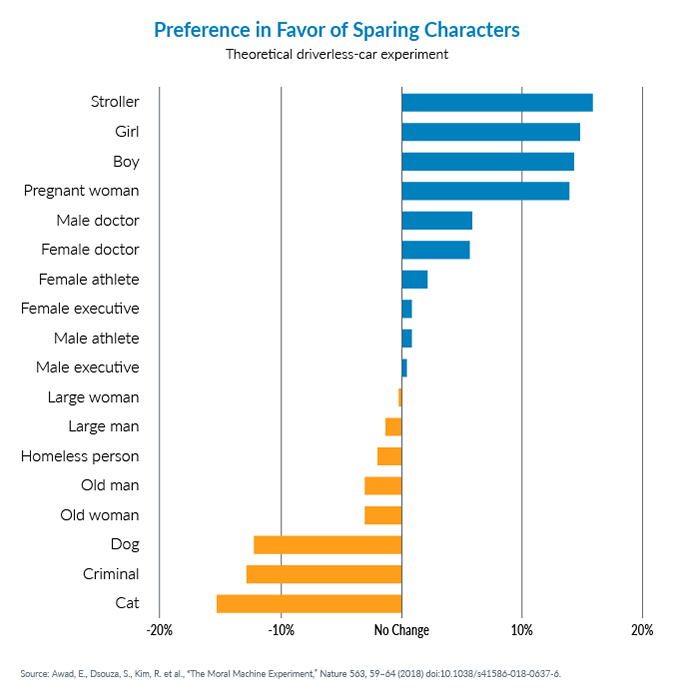

In this instance, collision is inevitable. How should the AV be programmed to respond? What guiding principles should be in play and how should an individual - or group of lives - be valued? Should the goal of an AV be to preserve an occupant’s life first, or spare as many lives as possible? Is the best alternative to veer to the left and kill the elderly woman? One study published in Nature magazine in October 2018 analyzed such a problem with the following results:

The graphic illustrates a modern take on the classic “trolley problem,” in which a hypothetical trolley barrels down the tracks. Ahead are five people tied to the tracks and unable to move. Standing some distance from the pending mishap, the operator can pull a lever that will shunt the trolley to a different set of tracks on which one person is standing unaware. Switching the trolley to this track will spare the five, but certainly kill the one person. Which is the more ethical choice? This is the intractable problem: How do we value and prioritize human life?

As AVs come closer to actuality, the trolley problem will move from thought experiment to reality. AV development will certainly include value judgments in those situations in which collisions - and possibly fatalities - are inevitable. How those judgments are made will be the product of an unprecedented confluence of technology, regulation and social discourse.