-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

PFAS – Rougher Waters Ahead?

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

Did you Know? A Brief Reflection on La Niña and El Niño

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

Gen Re’s valuable insights and risk transfer solutions help clients improve their business results. With tailor-made reinsurance programs, clients can achieve their life & health risk management objectives.

UnderwritingTraining & Education

Publication

Fasting – A Tradition Across Civilizations

Publication

When Actuaries Meet Claims Managers – Data-Driven Disability Claims Review Business School

Business School

Publication

Chronic Pain and the Role of Insurers – A Multifactorial Perspective on Causes, Therapies and Prognosis

Publication

Simplicity, Interpretability, and Effective Variable Selection with LASSO Regression Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Alzheimer’s Disease Overview – Detection and New Treatments

October 15, 2024

Cecil Ramotar

English

Alzheimer’s disease is a brain disorder and the most common type of dementia, affecting and destroying memory and thinking skills as it progresses. The disease exacts an incredible emotional and financial toll on its sufferers and their families. In recent years, a new class of disease-modifying treatment has emerged that shows some promise in slowing the progression of Alzheimer’s.

Before getting into an overview of new Alzheimer’s treatments, let’s start with a brief overview of the disease.

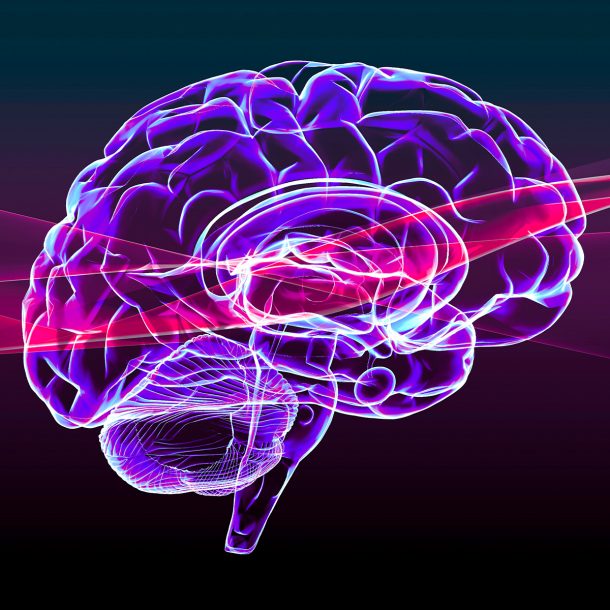

The Brain

The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) National Institute on Aging (NIA) expertly summarizes the complex workings of the human brain this way:

Brain cells, commonly called neurons, “have three basic parts: a cell body, multiple dendrites, and an axon. The cell body contains the nucleus, which houses the genetic blueprint that directs and regulates the cell’s activities. Dendrites are branch-like structures that extend from the cell body and collect information from other neurons. The axon is a cable-like structure at the end of the cell body opposite the dendrites that transmits messages to other neurons.”1

Several processes are essential for brain cells to function and survive over time, including the cells’ ability to communicate via electrical charges with other brain cells, metabolize cellular nutrients, and repair, remodel, and regenerate neurons.

Cognitive Decline and Mild Cognitive Impairment

Some degree of cognitive decline can be expected as part of the normal aging process. Between a normal loss of cognition associated with aging and definite dementia is a classification called Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI).

This table from the National Institute on Aging compares “healthy” age-related changes in memory to those observed in MCI versus dementia.2

Signs of Healthy Aging vs. Mild Cognitive Impairment vs. Dementia

|

|

Healthy Aging |

Mild Cognitive Impairment |

Dementia |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Sometimes forgetting which words to use |

✔ |

|

|

|

Losing things from time to time |

✔ |

|

|

|

Missing a monthly payment occasionally |

✔ |

|

|

|

Difficulty coming up with words |

|

✔ |

|

|

Losing things often |

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

Forgetting to go to important events |

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

Trouble having a conversation and/or reading and writing |

|

|

✔ |

|

Asking the same question or repeating the same story over and over |

|

|

✔ |

|

Difficulty with basic daily activities |

|

|

✔ |

|

Problems handling money and paying bills |

|

|

✔ |

|

Becoming lost in familiar places |

|

|

✔ |

|

Hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia |

|

|

✔ |

Source: National Institute on Aging: This is not a complete list of all symptoms associated with these conditions, but it is designed to show how the symptoms differ.

Alzheimer’s, a Dementia Subtype

Several types of memory loss fall under the general term “dementia” – the most common being Alzheimer’s, comprising 60%‑80% of all dementias. Other less common forms of dementia include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, Frontotemporal dementia, and Creutzfeldt‑Jakob disease.3

Risk Factors

Alzheimer’s

As the science around Alzheimer’s continues to evolve, so too does our understanding of risk factors that play a role in causing Alzheimer’s.

- The greatest known risk factor for “late-onset Alzheimer’s” is increasing age. Although Alzheimer’s is not caused by aging, getting older increases one’s chances of developing the disease.

- A family history of Alzheimer’s is also a risk factor: more specifically, someone is at higher risk of developing the disease if a first-degree relative (sibling, parent) has or had Alzheimer’s.4

- Another risk factor beyond individual control is genetics; some genetic factors increase one’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s.5

- Other risk factors are also closely linked to overall health and wellbeing, including chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease), lifestyle (e.g., alcohol consumption, sleep, exercise), and environmental surroundings (e.g., air pollution, exposure to cigarette smoke).

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, of Americans aged 65 and older, about 10.9% (or 6.9 million people) live with Alzheimer’s disease, with prevalence being skewed to older ages: 5.0% ages 65‑74, 13.2% ages 75‑84, and 33.4% for ages 85 and older.6

Mild Cognitive Impairment

There’s no single risk factor for MCI, although in some instances it may be due to early Alzheimer’s disease. There’s no single outcome for the disorder: Symptoms of MCI may remain stable for years, or MCI may progress to Alzheimer’s disease dementia or another type of dementia. In some cases, MCI may improve over time. Columbia University researchers estimate that 22% of those aged 65 and older within the U.S. have MCI.7

Patients with MCI may be assessed through several different diagnostic tools, including imaging and tests. In addition to physical and neurological exams, the diagnostic process may include lab tests and neuropsychological tests as well as brain imaging (MRI, CT scan, PET scan).

The Alzheimer’s Association website summarized MCI diagnosis this way:

“Mild cognitive impairment is a clinical diagnosis representing a doctor’s best professional judgment about the reason for a person’s symptoms. Individuals living with MCI who have an abnormal brain positron emission tomography (PET) scan or spinal fluid test for amyloid beta protein, which is the protein in amyloid plaques, are considered to have a diagnosis of MCI due to Alzheimer’s disease.”8

Alzheimer’s and the Amyloid Hypothesis

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive brain disorder hypothesized to be caused by amyloid deposits between neurons and abnormal accumulations of tau protein that form twisted threads called neurofibrillary tangles that collect inside neurons.9 This causes the brain to shrink and brain cells to eventually die. The loss of synaptic connections, reduction in glucose, and energy production within the brain lead to impaired memory, altered thinking processes, and changes in behavior and social skills – and possibly also include a reduction in neurogenesis.

Not surprisingly, these changes affect a person’s ability to function. The processes essential for brain health – cellular communication, metabolism, repair, remodeling, and regeneration – are disrupted, or deteriorate, in people with brain disorders. For example, an early loss of synaptic connections is characteristic in Alzheimer’s-related cognitive decline.10

Within the Alzheimer’s research community there have been two views on the amyloid hypothesis, which asserts “that abnormal accumulation and aggregation of β‑amyloid (Aβ) peptides (the main component of amyloid plaques) play a key role in triggering a cascade of pathological events that lead to the clinical syndrome of Alzheimer’s disease dementia.”11

- Opponents believe that amyloid deposition is not the direct cause of Alzheimer’s, and that the true reason remains unknown. In Alzheimer’s disease there is a complex relationship between amyloid pathology, neurological degeneration, and dementia. Comparative postmortem to living studies of axonal loss show that the severity of resulting cognitive impairment does not correlate well to the amount or distribution of amyloid plaque. This leads to the questioning of the validity of targeting amyloid for removal in symptomatic disease. In addition, there have been many clinical trials of anti-amyloid therapies for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s dementia over the past two decades that have failed – thus creating skepticism of the amyloid hypothesis in general.

- Adherents to the amyloid hypothesis think that a key role in triggering the Alzheimer’s dementia symptoms are caused by abnormal accumulation and aggregation of amyloid plaques. There is strong evidence by way of human genetics data, biochemical, histological, and animal model evidence that point to amyloid accumulation as a critical player in Alzheimer’s disease. There can be up to 15 years of lead time where brain amyloid can be detected prior to the onset of reduced cognition of Alzheimer’s. Elevated amyloid is also associated with a substantially increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia in the ensuing decade, which supports the concept of a long asymptomatic stage of Alzheimer’s. Thus, for prevention of clinical disease removing amyloid is generally considered a highly promising target.

Revival of the Anti-Amyloid Strategy

As detailed in a recent journal article, two major advances revived the anti-amyloid strategy for symptomatic Alzheimer’s:12

- “Development of accurate human biomarkers…that can detect the presence of amyloid plaques and tau pathology in the brain in both preclinical and symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease.” These include PET imaging, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, and emerging blood tests for beta-amyloid and tau measurements. These new biomarkers permit evaluation for initial treatment, clinical trials, monitoring of patients, and are useful for evaluating target endpoints for amyloid/tau removal in patients undergoing treatment. At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference held in July 2024, a large study on the result for the blood test PrecivityAD2 showed that it was 90% accurate at identifying Alzheimer’s disease, compared to 63% and 73% diagnosis accuracy by primary care physicians and memory care clinics respectively.13

- “Development of a new generation of Anti-Amyloid Antibody Treatments that target aggregated forms of beta-amyloid… and all robustly reduce the burden of existing amyloid plaques in the human brain.”

Anti-Amyloid Antibody Treatments

Lecanemab (Leqembi®), which received traditional FDA approval July 2023, was the first monoclonal antibody therapy to target and remove beta-amyloid from the brain.14 Donanemab (Kisunla™), also a monoclonal antibody, was approved in July 2024.15 Both therapies are administered by intravenous infusion and are indicated to treat early Alzheimer’s disease, specifically people living with MCI or mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease who have confirmation of elevated beta-amyloid in the brain.16

Both Leqembi and Kisunla drugs are anti-amyloids, proteins engineered to adhere to and identify beta-amyloids, a biomarker associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Immune cells then target the identified amyloid for destruction. While both drugs are anti-amyloids, each works differently to slow disease progression: “Leqembi targets small chains of linked‑up beta-amyloid proteins called protofibrils. By preventing these protofibrils from emerging, the drug prevents amyloid plaques from forming. In addition, it also targets amyloid plaques. Meanwhile, Kisunla only targets the beta-amyloid plaques.”17

The drugs are further differentiated by their administration protocols: Although each requires intravenous infusion at medical facilities, Leqembi is meant to be administered biweekly for an indefinite period and is bodyweight dose dependent, whereas the Kisunla protocol dictates monthly infusions during the initial treatment period. Unlike Leqembi, Kisunla is not bodyweight dose dependent, and it is meant to be discontinued when target reduction end points of brain amyloid deposits are achieved (measured by PET scans during treatment period).

In May 2024, Eisai submitted for FDA approval a subcutaneous injectable form of Leqembi; if the autoinjector is approved, patients would have the convenience of using at home whilst still having the option for continued care at a medical facility.18

It is important to note that Kisunla and Leqembi are designed to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in early-stage patients; neither is a cure, and neither can reverse or repair existing damage in the brain.

In a Kisunla research study, deterioration in thinking and memory were slowed 4.5 to 7.5 months when compared to the placebo group.19 The best clinical response was in those younger than age 75, with lesser symptoms and brain amyloid buildup.

Like all medications, taking either of these drugs comes with risks. Those undergoing treatment with Leqembi or Kisunla need to be regularly monitored for side effects, including infusion-related reactions, allergic reactions, brain swelling, or brain bleeds known as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA).20

Costs

In the U.S., for a person of average weight, one year of Leqembi costs $26,500; Kisunla, which doesn’t factor body weight in dosing, costs $32,000 annually. Patients receiving Kisunla treatment can stop taking the drug when their beta-amyloid is cleared to a predetermined level, thereby potentially reducing overall costs. Duration of treatment with Kisunla varies by individual, with research studies showing ranges of 6‑18 months.21

Diagnostic PET scans, ongoing brain scans, and additional medical care to monitor patients or treat side effects add considerable expense over and above the cost of the actual drugs.

Marketing and Healthcare Coverage Approvals

Subsequent to their FDA approvals in the U.S., both Leqembi and Kisunla and supporting care costs are covered by Medicare Part B under a National Coverage Determination – the patient has to have a diagnosis of MCI or mild Alzheimer’s disease, documented evidence of beta-amyloid plaques in the brain, and have a physician and appropriate clinical team who will participate in a qualifying registry to gather data on the medical status of patient as they undergo treatment.22

The injectable form of Leqembi being reviewed by the FDA is intended to be self-administered, and as such will not fall under Medicare Part B, but would be covered under a prescription plan/Medicare part D.23

Along with Medicare, the Veteran’s Administration and some larger insurers will cover Leqembi, but some insurance companies have chosen to exclude it, considering it an experimental treatment.24

Leqembi is approved for use in the U.K., China, South Korea, Israel, Hong Kong, and Japan. The U.K. approval came with conditional support: Leqembi will not be covered for patients seeking treatment through the National Health Service due to concerns over efficacy and safety.25 The European Medicines Agency refused to grant a marketing authorization for similar reasons.26 Other countries are expected to make decisions on approval for both Leqembi and Kisunla in the future.

Slow Uptake of Anti-amyloid Treatment in Marketplace

Despite its initial projections that 10,000 patients would be taking Leqembi by March 2024, Leqembi’s maker, Japan’s Eisai, modified their projections while noting that sales are increasing.27

Some of the hurdles facing more widespread treatment include:

- Medical experts’ skepticism over the anti-amyloid hypothesis and concerns over side effects and cost-benefit of treatment.

- Difficulties in identifying suitable patients and initiating treatment before advancing cognitive decline.

- Patient population limitations due to contraindicated conditions or medications (e.g., anti-coagulation / blood thinners).

- Difficulties securing the care of a neurologist for diagnosis and administration of drug.

- Hospitals and health systems have longer-than-expected periods to set up the infusion and supporting care protocols. Some treatment centers have limited patients to a narrow geographical radius in order to have ready access to patients in the eventuality of complications.

- Health systems are still trying to understand how coverage for the drug and supporting care will be administered so patients are not overwhelmed with high costs.

Outlook

The two drugs discussed were successful in garnering FDA approval after development and meeting target results in clinical trials. As of early 2024, there were approximately 134 drugs in various stages of clinical trials, and 171 ongoing studies – all targeting MCI and early Alzheimer’s.28 This is a rapidly emerging sector, and we look forward to the development of increasingly effective treatments in the future.

- “What Happens to the Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease?”, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging, Jan. 19, 2024, https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-causes-and-risk-factors/what-happens-brain-alzheimers-disease.

- “Signs of Health Aging vs. Mild Cognitive Impairment vs. Dementia”, Alzheimers.gov, https://www.alzheimers.gov/alzheimers-dementias/mild-cognitive-impairment.

- Alzheimer’s Association, “Types of Dementia,” https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia/types-of-dementia.

- “Alzheimer’s disease,” Mayo Clinic, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20350447.

- Ibid.

- Alzheimer’s Association, “2024 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures, Special Report, Mapping a Better Future for Dementia Care Navigation,” https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf.

- Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Oct. 24, 2022, https://www.cuimc.columbia.edu/news/one-10-older-americans-has-dementia.

- “Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)”, Alzheimer’s Association, https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia/related_conditions/mild-cognitive-impairment.

- “Alzheimer’s disease”, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20350447, and “What Happens to the Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease?”, https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-causes-and-risk-factors/what-happens-brain-alzheimers-disease

- “What Happens to the Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease?”, https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-causes-and-risk-factors/what-happens-brain-alzheimers-disease.

- Erik S. Musiek, Teresa Gomez‑Isla, David M. Holtzman, “Aducanumab for Alzheimer disease: the amyloid hypothesis moves from bench to bedside”, Journal of Clinical Investigation, Oct. 15, 2021, https://www.jci.org/articles/view/154889.

- Ibid.

- Alzheimer’s Association Press Release, “Alzheimer’s Disease Blood Tests Could Improve Diagnosis in Primary Care, Speed Recruiting for Research and Reduce Wait Times,” https://aaic.alz.org/releases-2024/blood-tests-alzheimers-biomarkers.asp.

- “FDA Converts Novel Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment to Traditional Approval”, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), July 6, 2023, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-converts-novel-alzheimers-disease-treatment-traditional-approval.

- “FDA approves treatment for adults with Alzheimer’s disease”, FDA, July 2, 2024, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-treatment-adults-alzheimers-disease.

- “Lecanemab Approved for Treatment of Early Alzheimer’s Disease”, Alzheimer’s Association, https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/treatments/lecanemab-leqembi; Fraiser Kansteiner, “After filing hitch, Eisai and Biogen begin rolling FDA submission for subcutaneous Leqembi”, 14 May 2024, https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/eisai-and-biogens-quest-subcutaneous-leqembi-back-track-thanks-fda-fast-track-tag; and Simon Spichak, “Leqembi Vs. Kisunla: An Alzheimer’s Drug Point-by-Point Comparison”, Being Patient, https://www.beingpatient.com/leqembi-vs-kisunla-for-alzheimers.

- Simon Spichak, “Leqembi Vs. Kisunla: An Alzheimer’s Drug Point-by-Point Comparison”, Aug. 28, 2024, https://www.beingpatient.com/leqembi-vs-kisunla-for-alzheimers.

- “Eisai Initiates Rolling Biologics License Application to FDA for LEQEMBI® (lecanemab-irmb) for Subcutaneous Maintenance Dosing for the Treatment of Early Alzheimer’s Disease Under the Fast Track Status”, Eisai Global, 15 May 2024, https://www.eisai.com/news/2024/news202430.html; Fraiser Kansteiner, https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/eisai-and-biogens-quest-subcutaneous-leqembi-back-track-thanks-fda-fast-track-tag.

- “5 Things to Know About Kisunla, The New Alzheimer’s Drug”, Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Research Foundation, July 3, 2024, https://www.alzinfo.org/articles/treatment/5-things-to-know-about-kisunla-the-new-alzheimers-drug.

- “FDA Approves Kisunla, A New Drug for Alzheimer’s Treatment,” Alzheimer’s New Jersey, https://www.alznj.org/fda-approves-kisunla-a-new-drug-for-alzheimers-treatment.

- Id. at note 18.

- “CMS announces new details of plan to cover new Alzheimer’s drugs”, CMS Newsroom, June 22, 2023, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/cms-announces-new-details-plan-cover-new-alzheimers-drugs; “What is lecanemab?”, Alzheimer’s Society, Aug. 22, 2024, https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/blog/what-lecanemab.

- “Statement: Broader Medicare Coverage of Leqembi Available Following FDA Traditional Approval,” CMS Newsroom, July 6, 2023, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/statement-broader-medicare-coverage-leqembi-available-following-fda-traditional-approval.

- Healthline, “Some Insurers May Not Cover New FDA-Approved Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment,” https://www.healthline.com/health-news/some-insurers-may-not-cover-new-fda-approved-alzheimers-disease-treatment-report-finds.

- “Alzheimer’s Association Commends United Kingdom’s Approval of Leqembi, But Condemns Decision to Deny NHS Access”, Alzheimer’s Association, Aug. 22, 2024, https://www.alz.org/news/2024/uk-approves-leqembi-denies-nhs-access; “What is lecanemab?”, https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/blog/what-lecanemab.

- European Medicines Agency, “Leqembi”, Aug. 5, 2024, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/leqembi.

- Tom Murphy, “It’s the first drug shown to slow Alzheimer’s. Why is it off to a slow start?”, AP News, April 13, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/alzheimer-leqembi-slow-start-f9022b85b16cc6de4491594ce875657b; Julie Steenhuysen, “Alzheimer’s drug adoption in US slowed by doctors’ skepticism”, Reuters, April 23, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/alzheimers-drug-adoption-us-slowed-by-doctors-skepticism-2024-04-23/; Ben Adams, “Neurologists paint bleak Leqembi launch picture as Alzheimer’s drug trips up on a host of challenges”, Fierce Pharma, Feb. 27, 2024, https://www.fiercepharma.com/marketing/neurologists-paint-bleak-leqembi-launch-picture-alzheimers-drug-trips-host-challenges.

- BrightFocus Foundation, “What’s Next for Alzheimer’s Disease Treatments: A 2024 Forecast,” March 26, 2024, https://www.brightfocus.org/alzheimers/article/whats-next-alzheimers-disease-treatments-2024-forecast#.