-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

PFAS Regulation and Development at the European Level with Focus on Germany and France

Publication

The CrowdStrike Incident – A Wake-Up Call for Insurers?

Publication

Decision-Making in the Age of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Publication

Buildings Made of Wood – A Challenge For Insurers?

Publication

Cat Bonds – A Threat to Traditional Reinsurance? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

Gen Re’s valuable insights and risk transfer solutions help clients improve their business results. With tailor-made reinsurance programs, clients can achieve their life & health risk management objectives.

UnderwritingTraining & Education

Publication

Fasting – A Tradition Across Civilizations

Publication

When Actuaries Meet Claims Managers – Data-Driven Disability Claims Review Business School

Business School

Publication

Chronic Pain and the Role of Insurers – A Multifactorial Perspective on Causes, Therapies and Prognosis

Publication

Simplicity, Interpretability, and Effective Variable Selection with LASSO Regression Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

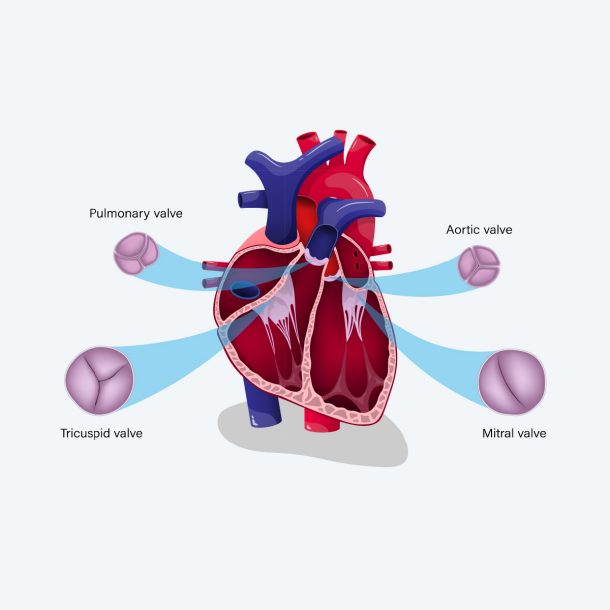

An Overview of Mitral Regurgitation Heart Valve Disorder – and Underwriting Considerations

Mitral regurgitation, or mitral insufficiency, is a common form of heart disease where the mitral valve doesn’t close properly as the heart pumps out blood during left ventricular systole (contraction), allowing a backflow of some blood into the left atrium (regurgitation). Mitral regurgitation (MR) is the second most common form of valvular heart disease after aortic stenosis (AS) with a similar prevalence in men and women.1

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is the most common cause of MR.2 MVP has a similar prevalence in men and women, with a greater risk of complication in men.3 Ischemic heart disease is the next most common cause. Ischemic MR results from papillary muscle dysfunction, regional left ventricular dysfunction and global left ventricular dilation resulting from infarcted myocardium.

The incidence of MR has increased over the past decades, likely partially due to the greater availability of echocardiography resulting in incidental findings of MR. Trivial MR (i.e., a finding of no concern) is detectable in up to 70% of healthy adults.4

Overview of Mitral Regurgitation

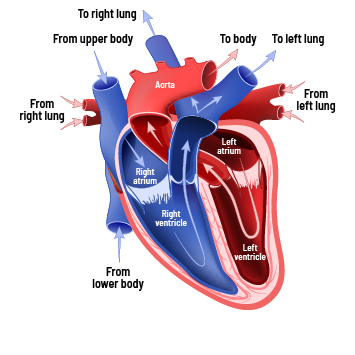

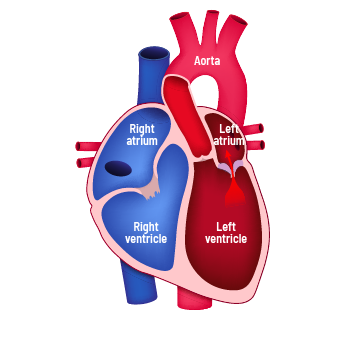

The left heart is composed of the left atrium, left ventricle, mitral valve and aortic valve. The function of the left heart is to collect oxygenated blood from the lungs and then pump this blood throughout the body. The left atrium receives oxygenated blood from the lungs during ventricular systole. With increasing volume in the left atrium, the pressure becomes higher than in the left ventricle that is moving blood forward into the aorta.

Left Heart Anatomy and Blood Flow

This pressure gradient pushes the mitral valve open. Early ventricular diastole (E) begins with blood flowing from the left atrium into the left ventricle. Late ventricular diastole (A) ends with left atrial contraction emptying as much blood as possible into the left ventricle. Increased pressure in the left ventricle during systole keeps the aortic valve open and pushes the mitral valve shut. The left ventricular contraction pumps oxygenated blood through the open aortic valve into the aorta.

Mitral Valve Function and Anatomy

The mitral valve acts as a one-way inlet for blood flow into the left ventricle and prevents the backward flow of blood into the left atrium. The ventricles fill during ventricular diastole. The atria fill during ventricular systole.

The mitral valve apparatus is composed of the mitral annulus (ring), two leaflets, the chordae tendineae and the papillary muscles. The mitral annulus surrounds the bicuspid valve and fits firmly in the opening between left atrium and left ventricle. Chordae tendineae run between the mitral leaflets and the papillary muscles that are attached to the lower walls of the left ventricle. The purpose of the chordae tendineae and papillary muscles is to help control proper mitral valve function by keeping the mitral valve anchored and well-centered. Contraction of the papillary muscles counteracts the high-pressure during systole and prevents the mitral leaflets from being pushed backward into the atrium. Impairment of any of these structures may lead to mitral regurgitation.

Causes for Mitral Valve Regurgitation

Primary MR is caused by any abnormalities of the mitral valve apparatus. Examples include mitral annulus calcification, mitral valve prolapse (MVP), mitral leaflets damaged by endocarditis or rheumatic heart disease, chordae tendineae elongation or rupture, papillary muscle fibrosis, calcification, or rupture. MVP, the most common cause, results from the bulging of one or both MV leaflets into the left atrium during ventricular systole.

MVR – Bulging of one or both MV leaflets into the left atrium during ventricular systole

Secondary causes of MR include damage to the left ventricular myocardium through ischemia, infarction, or cardiomyopathy. Dilated cardiomyopathy can cause the mitral annulus to dilate, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy can cause deformation of the mitral leaflets, chordae slack or displacement of the mitral apparatus. Other secondary causes of MR include collagen vascular diseases, trauma, carcinoid, and exposure to certain appetite suppressant drugs.

Clinical Phases

Symptoms of chronic MR include decreased exercise tolerance with dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, palpitations, and tachycardia. These symptoms correlate with clinical phases of chronic mitral regurgitation. The clinical phases include the:

- Compensation Phase

- Transitional Phase

- Decompensation Phase

During the Compensation Phase, there is a gradual development of volume overload in the left atrium and left ventricle (LV) without diminished LV function. The myocardium compensates for the increased burden caused by MR and the individual can be asymptomatic for years or decades. Symptoms may not manifest until the Transitional Phase when the heart can no longer keep pace with the persistent and increasing volume overload. Symptoms progress during the Decompensation Phase as LV function is decreasing. Eventually symptoms of congestive heart failure appear.

Acute Mitral Regurgitation

Acute MR will rarely be part of an underwriting assessment. It is secondary to an extraordinarily sudden event, such as trauma or myocardial infarction, resulting in significant myocardial damage. Some portion of the valve structure gets damaged, deformed, distorted, or even severed, causing sudden dysfunction of the valve. Symptoms will be severe with abrupt onset. Other causes for acute MR include papillary muscle or chordae tendineae rupture leading to cardiogenic shock. Without immediate medical intervention, death could result.

Diagnosis

Auscultation with a stethoscope will reveal MR as a high-pitched holosystolic murmur at the apex radiating to the back or clavicular area. Loudness of the murmur does not correlate well with the severity of regurgitation. Also, a third heart sound is commonly heard. MVP with MR will be heard as a mid-systolic click with a late systolic murmur, heard best at the apex. It is characteristic for this murmur to be accentuated by standing or Valsalva maneuver and diminished with squatting.

Echocardiography is the preferred method for diagnosing, monitoring and quantifying MR. Echocardiography, in 2‑D and M‑Mode, reveals the anatomic basis for MR, such as mitral annular calcification or degenerative mitral leaflets. Findings of left atrial enlargement (LAE), left ventricular dilation, and left ventricular hyperkinesia, and evidence of pulmonary hypertension, help to determine the appropriate disease phase.

Additionally, more specific parameters that may be found on echocardiography reports include measurements for Color Flow Doppler regurgitant jet, Regurgitant Fraction (RF) and Effective Regurgitant Orifice area (ERO). These measurements can help to assess the degree of MR more accurately.

- Color Flow Doppler regurgitant jet measurements assess the area of regurgitant jet relative to size of the left atrium.

- Regurgitant Fraction (RF) measures the percentage of left ventricular stroke volume that regurgitates into the left atrium.

- Effective Regurgitant Orifice area (ERO) measures the area of regurgitant flow at the level of the mitral valve.

(See the table below showing how these measurements can be used to assess severity and clinical phases of MR.)

Cardiac catheterization is invasive but allows for more accurate assessment of MR, left ventricular function and pulmonary artery pressure.

Treatment

Patients with asymptomatic MR with normal heart and valve anatomy do not require treatment. Preventive antibiotic treatment for infective endocarditis before dental or surgical procedures was a common protocol in the past. These guidelines were updated in 2006. People with MR, who have not undergone heart valve surgery, no longer require preventative antibiotic treatment.

Mild to moderate MR in the elderly, caused by annular calcification, does not require surgical intervention. Symptomatic moderate-to-severe MR is treated with vasodilators, such as ACE inhibitors, over the short-term. These drugs act to reduce left ventricular volumes and improve symptoms.

Symptomatic moderate-to-severe MR with heart enlargement will require surgery to repair or replace the mitral valve. A bioprosthetic valve or mechanical valve may be used. A mechanical valve replacement will require long-term anticoagulation therapy.

Complications

Over time, chronic MR will cause changes to the heart muscle (myocardial remodeling) and the vascular system. Initially the heart can compensate for the gradual development of volume overload caused by MR. Left atrial enlargement is the first response to significant MR volume increase. Elevated ejection fraction (EF) occurs as an adaptive response to maintain adequate cardiac output, compensating for the volume loss by regurgitant flow into the left atrium. There usually are no symptoms during this Compensation Phase. These adaptive changes provide for normal left ventricular function with normal heart rhythm. Any remodeling changes at this stage are reversible.

Myocardial remodeling progresses during the Transitional Phase. As volume overload persists, dilation of the left ventricle will be seen in addition to the previous findings of LAE. EF decreases in the Transitional Phase. Since the EF is declining from the elevated EF found during the Compensation Phase, it may appear to be normal during the early Transitional Phase. Don’t be fooled! As LV function diminishes, the EF will drop further and become unmistakably low and abnormal. Symptoms likely to develop during this phase include decreased ability to exercise or be active, shortness of breath and palpitations. Also, as the left atrium enlarges, atrial fibrillation may develop. Not all people will experience symptoms. In the transitional phase, remodeling becomes irreversible. Surgical treatment may be considered at this point.

As mitral valve regurgitation worsens, myocardial remodeling increases, and proper LV function becomes severely inhibited. The heart muscle begins to fail. This is known as the Decompensation Phase or end-stage MR. During this phase, the left ventricle can no longer compensate for the regurgitation and its cascade of alterations. The EF declines to lower and lower levels during this phase. Both the left atrium and left ventricle become pathologically enlarged and heart function becomes inefficient. Abnormal heart rhythms can occur. Pulmonary hypertension develops due to flow reversal from the left atrium into the pulmonary veins. Over time all these irreversible changes lead to congestive heart failure (CHF).

Underwriting Mitral Regurgitation

Underwriting chronic mitral regurgitation requires the use of clinical criteria and measurable data to assess the severity of the valve disorder. Clinical criteria may include heart murmur and mid-systolic click heard on auscultation, chest pain, palpitations, arrhythmia, or an ECG with notched P‑waves (consistent with any atrial enlargement). Heart murmur intensity heard on auscultation correlates poorly with the severity of MR.

Measurable data concerning the severity of MR is obtained from echocardiography, cardiac MRI, and cardiac catheterization. The Echocardiogram with Doppler measurements is the most prevalent source of measurable data for MR and shows the anatomic basis for the disease. Measurable data includes left atrial and left ventricle dimensions, degree of regurgitation, left ventricular EF, Regurgitant Fraction (RF), Color Flow Doppler Regurgitant Jet, and Effective Regurgitant Orifice area (ERO).

Understanding the Measurable Data – Severity of MR

Trace to Mild (1+) MR

Clinical findings of mild MR include possible heart murmur with an absence of other clinical criteria. Echocardiography findings show normal left atrial and left ventricular dimensions, Color Flow Doppler regurgitant jet of <20% of LA area, an RF of <20%, ERO area of <20 mm2 and an EF of 55% or less. Mild MR may never progress, and in a heart with normal structure and function, may be assessed at standard rates. MR becomes significant in the presence of MV abnormalities, such as leaflet prolapse, vegetation or calcification as well as left atrial enlargement and left ventricular dilatation. In this context, mild MR will require a low to moderate substandard rating. Note trivial MR is an insignificant physiologic finding.

Moderate (2+) MR

Moderate MR is likely clinically asymptomatic with a possible murmur and/or notched P‑waves on an ECG. This characterizes the Compensation Phase of MR. Echocardiography findings include mild left atrial enlargement, Color Flow Doppler regurgitant jet of <20% of LA area, an RF between 20‑30%, ERO area of 20‑24 mm2, and EF of >60%. Cases in this category will require mild to moderately substandard rates.

Moderately severe (3+) MR

Moderately severe MR represents the Transitional Phase of mitral regurgitation. Symptom onset may begin here as well as findings of murmur, ECG changes and enlarged heart on CXR. Echocardiography will show normal to moderate left atrial and left ventricular dilation, left atrial dimension will be greater than right atrial dimension, Color Flow Doppler regurgitant jet of 20‑40% of LA area, RF between 30‑49%, ERO area of 25‑39 mm2, and EF between 50‑59%. Cases in this category will range between high substandard and declination.

Severe (4+) MR

Severe MR represents the Decompensation Phase or end stage of mitral regurgitation. This stage is characterized by clinical symptoms, murmur, ECG changes, ventricular tachycardia and/or atrial fibrillation and cardiomegaly. Echocardiography shows moderate to severe left atrial and left ventricular dilatation, Color Flow regurgitant flow jet of >40% of LA area, RF of >50%, ERO area of 40 mm2 or more and EF <50%. These cases are uninsurable.

Tabular overview of various parameters for assessing phase and severity grade of mitral regurgitation

|

Clinical Phase |

Grade 1 |

Compensation Grade 2 |

Transitional Grade 3 |

Decompensation Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

LV Size |

|

Normal |

Normal or dilated |

Dilated, except acute MR |

|

EF |

>55% |

<60% |

50-59% |

<50% |

|

Mitral regurgitation |

1+ |

2+ |

3+ |

4+ |

|

Color Doppler regurgitant jet |

<20% of LA area |

<20% of LA area |

20-40% of LA area |

>40% of LA area |

|

Regurgitant orifice area (ERO) |

<20 mm2 |

20-24 mm2 |

25-39 mm2 |

40 mm2 and above |

|

Regurgitant faction (RF) |

<20% |

20-30% |

30-49% |

>50% |

Left Atrial Enlargement

|

|

|

Normal |

Mild |

Moderate |

Severe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diameter in cm |

Men |

<4.1 |

4.1-4.6 |

4.7-5.1 |

>5.2 |

|

Diameter in cm |

Women |

<3.9 |

3.9-4.2 |

4.3-4.6 |

>4.7 |

Sources: Bonow: Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Texbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, 9th ed., Chapter 66‑Vascular Heart Disease; and Goldman: Goldman’s Cecil Medicine, 24th ed., Chapter 75‑Vascular Heart Disease.

Other Underwriting Considerations

- Age is also an important aspect in the risk selection of mitral regurgitation.

MR is a progressive disorder. The earlier the onset of MR, the more time there is for progression. Therefore, younger ages may require a higher rating than older ages. - There are multiple factors that impact progression of MR.

Chronic MR is a slowly progressive disease that usually remains asymptomatic and stable for many years. MR progresses more rapidly in patients with connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan syndrome. MR from rheumatic heart disease may take decades to develop after a bout of acute rheumatic fever. Rheumatic heart disease was considered a major cause of isolated MR in the U.S. when rheumatic fever was a major health hazard, and this remains the predominate valvular sequela today in countries where rheumatic fever is still prevalent.5 - Specific left atrial sizes are not aligned with specific mitral regurgitation levels.

There are, however, estimates for general severity of enlargement. Parameters can be found in the American Society of Echocardiography.

Conclusion

Underwriting mitral valve regurgitation is a complex process requiring an understanding of left heart anatomy and circulatory function. Clinical symptoms and measured data need to be evaluated to correctly classify the phase and stage of the disease.

In some cases, the delineation of disease phases may not be clear due to incongruence of clinical symptoms and/or measured data. Lack of current data or inconsistent data makes assessment a challenge.

Keep the following points in mind when underwriting MVR:

- Echo assessment takes precedence over murmur assessment.

- Combine echo parameters and clinical criteria to assign impairment grade.

- Beware of deceptively high EF in known progressive disease as an indication of the compensation phase.

- When parameters overlap different grades of regurgitation, look for the best overall fit or apply an intermediate classification. Consult a Medical Director when in doubt.

- After surgical intervention, use the current valve assessment in addition to type of valve surgery to complete MR risk assessment.

I hope this overview was helpful in improving your understanding of underwriting considerations for this complex but common condition. It may be helpful to review your underwriting practices to ensure a rewarding conclusion when assessing Mitral Regurgitation. Gen Re is available for assistance.

Endnotes

- Jones EC, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, et al., “Prevalence and Correlates of Mitral Regurgitation in a Population-based Sample (the Strong Heart study)”. Am J Cardiol. 2001, 87: 298‑304. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11165964.

- Stanford Medicine, “What Are Mitral Valve Stenosis and Regurgitation?”, https://stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-conditions/blood-heart-circulation/mitral-valve-stenosis-regurgitation/causes.html#:~:text=Mitral%20valve%20prolapse%3A%20Prolapse%20is,syndrome%2C%20and%20floppy%20valve%20syndrome.

- Freed LA, Levy D, Levine RA, et al., “Prevalence and Clinical Outcome of Mitral-valve Prolapse”. N Engl J Med 1999,341: 1‑7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10387935.

- Singh JP, Evans JC, Levy D, et al., “Prevalence and Clinical Determinants of Mitral, Tricuspid, and Aortic Regurgitation (the Framingham Heart Study)”. Am J Cardiol 1999; 83:897. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10190406.

- Lembo, Nicholas J, et al., “Mitral Valve Prolapse in Patients With Prior Rheumatic Fever”. Circulation 77, No. 4, 830‑836, 1988. www.ahajournals.org.

Gary Kranich

Sr. Underwriting Specialist