-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

Gen Re’s valuable insights and risk transfer solutions help clients improve their business results. With tailor-made reinsurance programs, clients can achieve their life & health risk management objectives.

UnderwritingTraining & Education

Publication

The Key Elements of Critical Illness Definitions for Mental Health Disorders

Publication

What Are We to Make of Cannabis Use in The Insured Population? Business School

Business School

Publication

Knife or Needle: Will the New Weight Loss Medication Replace Bariatric Surgery?

Publication

Weight Loss Medication of the Future – Will We Soon Live in a Society Without Obesity? Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Understanding the Effect of Unemployment on Suicide – What Can We Learn From the Pandemic?

September 30, 2021

David Hatherell,

Thea Weyers

English

Death by suicide is sudden and often unexpected, leaving many who are close to the deceased with questions that are difficult and sometimes impossible to answer. They may have a strong need to understand the contributing factors that led to such event; however, it has been proposed that suicide may tell us more about the world in which the person lived, rather than their personal history and circumstances alone (so-called “coupled behaviour”).1

A perfect storm for suicide risk?

Early on in the COVID‑19 pandemic, concerns of a possible rise in suicide rates were expressed. Many surveys reported a negative impact on the mental health of the general population with increased levels of anxiety, stress and depression.2 We ask the question: Did the coronavirus pandemic create a perfect storm for suicide risk?

It’s possible to argue that the downsizing of the economy and the need for medical systems to focus their resources on tackling COVID‑19, added an additional threat or stress to people living with mental illness, a vulnerable group already at higher risk for suicide and self-harm. The pandemic may have exacerbated and accelerated the existential and complex issues that are already a precursor to suicidal behaviour.

These core stresses or threats come from various sources: anxiety about infection, isolation, disruption in critical mental health care services, domestic violence, and alcohol and substance abuse, as well as the effects of a recession such as unemployment.

To try to give clarity to these complex issues, we evaluated whether economic factors such as unemployment may aggravate existing challenges, resulting in higher suicide rates.3 It is also worth noting that the challenge becomes somewhat circular, as a strong link between increased substance abuse and suicide exacerbates the effect of economic challenges which could lead to higher levels of unemployment.4

What does the data tell us?

Suicide rates by country are published annually by the World Bank, along with unemployment rates and gross domestic product (GDP) figures. This data source includes indicators for 266 countries in total. In this investigation, unemployment rates are used to assess if a specific life event may have occurred, while GDP figures give us an indication of how suicide trends differ by the size of a given economy. Analytical techniques are used to help us understand how suicide, unemployment and GDP are related.

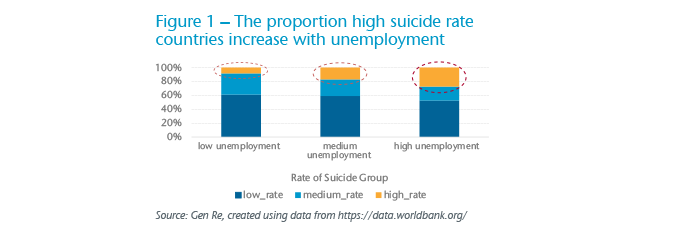

From this, we observe that both the level of unemployment and the annual change in unemployment rate are correlated with suicide rates. Figure 1 shows that split of suicide categories (low-medium-high rate) trends towards countries having a higher suicide rate as unemployment increases.

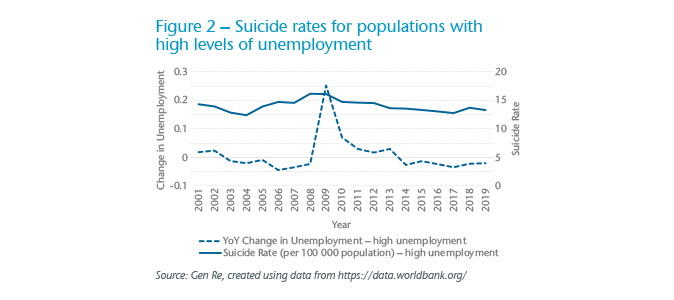

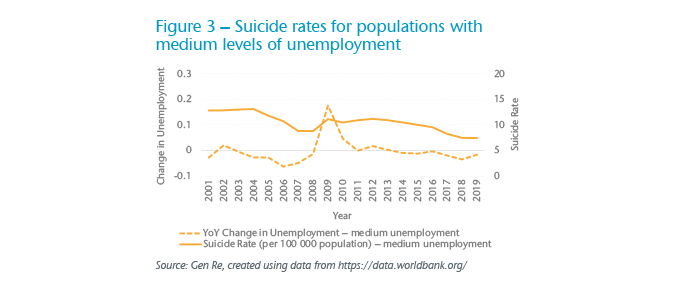

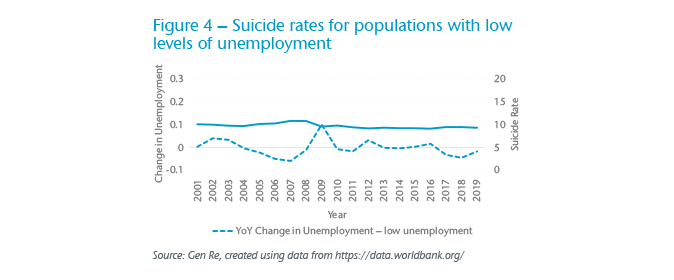

The figures below show some correlation between suicide rates and the year-on-year change in unemployment. It is, however, important to note that the suicide rate (per 100,000 population) in countries with high unemployment levels was already rising before the 2008 global financial crisis. The suicide rate also appears higher and more volatile in populations with higher unemployment levels.

With the above in mind, we see there is a relationship between suicide rates and unemployment. However, the link between suicide rates and pandemic events remains uncertain. Populations with high levels of unemployment showed an increase in suicide rates from 2003, which is associated with the SARS global outbreak. This could indicate that a pandemic may aggravate existing challenges, resulting in potential long-term effects. On the other hand, the relationship observed may be a matter of correlation and not causation.

Weighing increased risks against protective factors

Most studies to date have shown that suicide rates have not been affected by the COVID‑19 pandemic.5 A recent investigation found no significant evidence of an increase in suicide rates during the pandemic when observing data from 21 countries,6 despite World Bank data showing that unemployment levels in these countries had increased during this time. However, multiple surveys tell us that the demand for mental health care during the pandemic has increased, and a widespread disruption in many kinds of critical health services has ensued.7 With mental illness being one of the main risk factors for suicide, how can both be true?8

Counterintuitive as it may be, the pandemic that brought along increased risks, also brought about certain protections and a shift in risk factors. Most people had to adapt their lifestyle to new work and social environments. With a greater sense of community and shared identity came widespread outpourings of charity, empathy and support for others and a mutual goal to get through the pandemic together.9 For some, it may have been the belief that it will soon be over that prevented extreme feelings of despair, often associated with suicide attempts.10 One difference to previous recessions is that countries had provided financial relief to eligible individuals.11 This may have prevented the breadwinner from feeling hopelessness.

Possible longer-term impact

Although most studies have shown little impact of the pandemic on suicide rates, some countries have reported varying patterns and question the impact of the pandemic over the long run.

Historically, the adverse mental health effects of previous pandemics affected more people in the long run and lasted longer than the acute health effects. For example, the SARS global outbreak in 2003 was associated with a 30% increase in suicides in people over the age of 65.12 The long-term effect on mental health needs and possible impact on suicide rates may continue long after the infectious outbreak resolves.

While we cannot see a direct correlation between a pandemic and rising suicide rates, we can certainly observe that it aggravates factors that we know have a direct impact. We can also observe a distinct increase in activity around mental health issues, and demand for them to be addressed.

With that in mind, perhaps the real learning to focus on is not the statistics, but rather the possibility that COVID‑19 gave greater permission for us all to talk more freely about mental health, to express our concerns without fear of stigma, and to enable people at risk to reach out to those nearby. It is possible that COVID‑19 may have narrowed observed generational differences with openness to mental health-related discussions.

However, the longer-term correlation between pandemics and suicide is concerning. It suggests that society is not taking enough advantage of the very narrow window presented to step in and build on the channel that has opened. Just like life after a pandemic, normality returns, and as the core, direct threats impact the mentally vulnerable as before, society shifts them to the uncomfortable margin once again.

Summary

It’s vital for insurers to ensure that their underwriting and claims practices are geared toward identifying and managing the potential tail of increased mental health needs that may continue long after the infectious outbreak resolves. Now more than ever, practices should focus on holistic assessment and early intervention to better manage the risks associated with mental illness.

September is National Suicide Prevention Awareness Month. Useful information and resources can be found at: https://www.nami.org/get-involved/awareness-events/suicide-prevention-awareness-month.