-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Actuarial Insights on Heat-Related Mortality and Morbidity

July 16, 2024

Sarah Hogekamp

English

Hot weather extremes have increased globally since the 1950s and – with very few exceptions – have affected every region, as the AR6 Synthesis Report of the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) shows.1 Heat and high temperatures are direct contributors to increases in heat-related mortality and morbidity in North America, Europe, Africa, Australasia2 and some regions in Asia. Furthermore, they have caused negative health impacts indirectly through changes in vector- and water-borne diseases in several regions, including Central and South America and Asia.3

The impact of heat extremes on morbidity and mortality has been observed around the world in recent years: The 2003 heatwave in Europe caused an estimated 70,000 deaths.4 To put this into perspective, the flu causes between 15,000 and 70,000 deaths each year for European citizens.5 In 2022 Japan experienced nine extremely hot days (35°C or higher) in a row instead of a total of nine extremely hot days in a year. Consequently, more than 14,000 people required emergency care for heat stroke, and it is estimated that in a hot year, the excess deaths can reach up to 10,000 people.6 Several countries in South America experienced devastating wildfires in 2023 through a combination of long-term increases in temperatures and the recent El Niño, with the heat expected to be even worse in 2024.7

These events have a demonstrable impact on human health and mortality trends. Globally, 2023 was the hottest year on record.8

Health and Heatwaves

The heatwaves referenced were extreme weather events that created dents in health and mortality. In general, extreme heat has several adverse health effects, including but not limited to:

- Stress to the cardiovascular system, which actively works to regulate the body’s temperature. If the stress becomes too great, dizziness, a sudden drop in blood pressure or heat stroke can occur.

- Stress to the renal system, which is sensitive to dehydration. A higher outdoor temperature increases the body’s water consumption. If there is no adjustment in water intake, this can be detrimental to health, especially to the kidneys.

- Increased morbidity of several mental health conditions, including affective disorders, schizophrenia, neurotic and anxiety disorders. Mental health conditions are a major risk factor for heat-related mortality.9

- Reduced physical activity to avoid heat stress.

- In combination with low precipitation, extreme heat increases the risk of drought and wildfires. While the wildfires put peoples life’s in the affected region in imminent danger, the smoke from the wildfires can travel long distances and reduce air quality in far-away regions, putting many more people at risk of newly emerging or worsening respiratory illnesses.10

Studies show that in addition to the highest age bands, children, the chronically ill, outdoor workers, pregnant women, and people in socially and economically disadvantaged urban areas are particularly exposed to heat-related health risks.11

Heatwave Mortality Across Europe

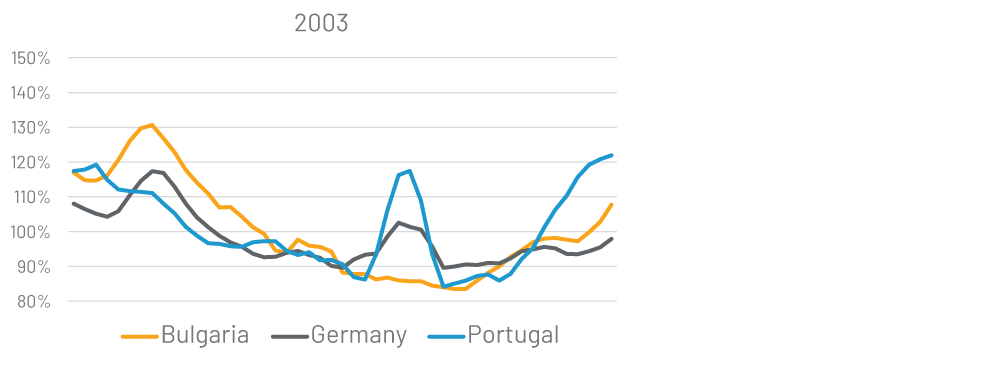

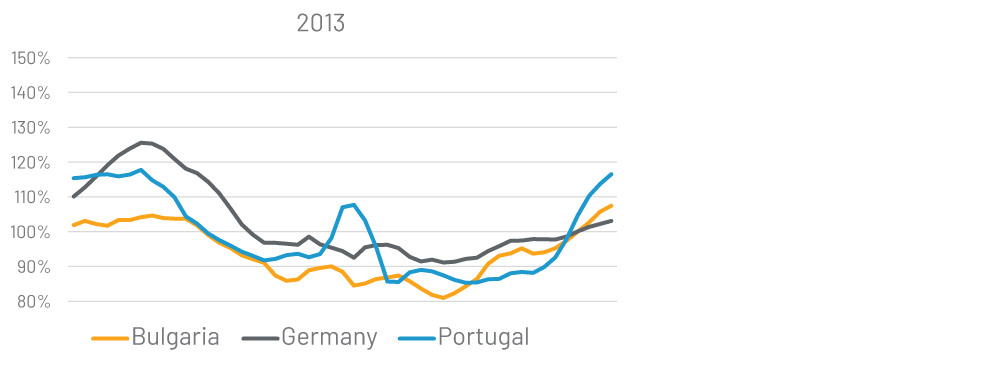

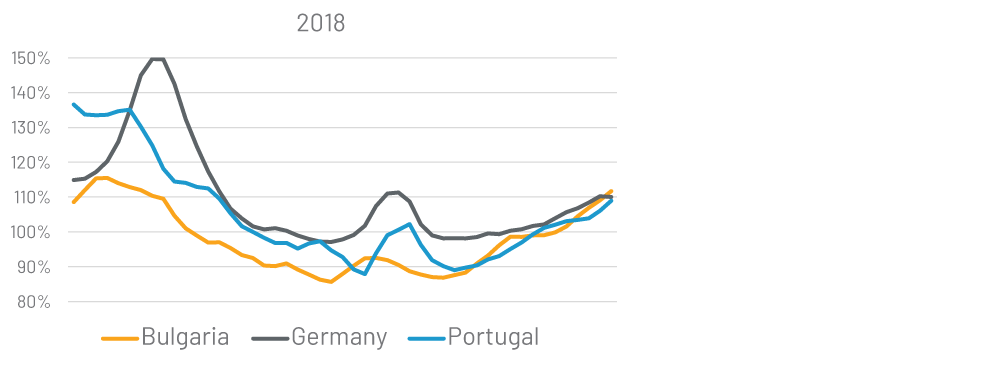

The significant mortality impacts of the aforementioned 2003 heatwave are not the only example of heat-related mortality that affected Europe in the recent past. Different health care systems, climate zones, population structures and other country-specific features can result in different mortality observations. Figure 1 shows the four-week moving average of deaths per week for the years 2003, 2013 and 2018 compared to the average of all weeks in a country from 2000‑2019 in Germany (central Europe), Bulgaria (southeast Europe) and Portugal (southwest Europe). During the selected years, summer mortality appears to be elevated in Germany and Portugal and – to a lesser extend – in Bulgaria.

Figure 1 – Four-week Moving Average Deaths per Week in 2003, 2013 and 2018 for Bulgaria, Germany and Portugal Compared to the Country-specific Average of All Weeks in 2000‑2019

Source: Data from Short-Term Mortality Fluctuations (STMF) data series; Human Mortality Database; Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany), University of California, Berkeley (USA) and French Institute for Demographic Studies (France). Available at www.mortality.org, retrieved April 2, 2024.

Influenza Influence

A logical next step after investigating rising temperatures and the resulting heat mortality is to look at the flipside: cold mortality. Can the increased mortality during heatwaves be offset by reduced cold mortality? To answer that question, we must distinguish between cold mortality and mortality during the cold season.

One major contributor to mortality during the cold season in Germany is influenza. While there is a correlation to cold temperature, it is not exclusive, and many additional factors ultimately determine the number of influenza cases. Although seasonal influenza occurs in winter in both the northern and southern hemispheres, factors such as seasonal variations in host immune response, changes in influenza strains and environmental factors such as humidity and UV radiation also influence influenza activity12 and, indirectly, influenza mortality. So even if the winters did become milder with climate change, influenza activity might still be significant.

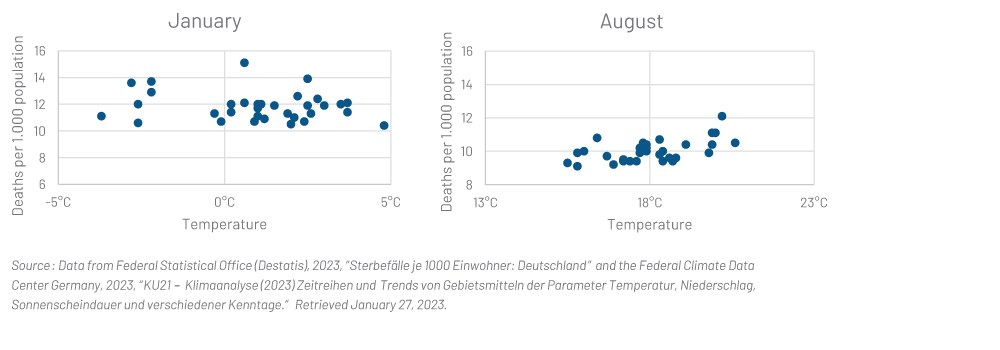

Figure 2 shows that overall mortality per 1,000 inhabitants in Germany is higher in winter (e.g., January), but the correlation between temperature and mortality appears much weaker than it does in summer (e.g., August). While the analysis lacks an age-standardization and should therefore be handled with care, it clearly hints toward a stronger relationship between summer and heat deaths compared to winter and cold deaths, where influenza activity might play a role in dispersing the picture.

Figure 2 – Monthly Mortality per 1,000 Inhabitants by Mean Monthly Temperature in Germany, 1990‑2019

Temperature-related Mortality in the United States

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reported between 1 and 3.5 heat-related deaths per 1 million people between 1999 and 2018 in 50 states and the District of Columbia.13 These figures include all deaths where heat is reported as an underlying or contributing cause on the death certificate. However, the agency notes that this official number likely underestimates the actual number of heat-related deaths.

A study on excess mortality during extreme heat events in the United States found generally decreasing vulnerability over time on a national level that has recently slowed down. On the one hand, this hints toward improvements in adaption to heat; on the other hand, the slowdown is being attributed to an uptake in the frequency of extreme heat events and an aging population. The decreasing trend is also not uniform across regions. Most notably, there has been an increase in mortality during extreme heat events in Florida, and the Pacific region has experienced high year-to-year variability.14

In a scenario without future demographic changes and adaption to a changing environment, the U.S. Global Change Research Program finds a net increase in projected future mortality. Based on this scenario, the increased mortality from heat is higher than the offset through reductions in cold-related mortality.15

Inevitable Adaptation

This being said, it’s not all bad news. If we look at the temperature with the lowest mortality, we clearly see the optimal temperature varies by region and appears to be much higher in warmer regions than in cold ones. Often, the warmer a country is, the higher the optimal temperature.16 In addition to temperature, regions may differ in their demographics, socioeconomics and other environmental factors, such as precipitation. These observations clearly support the assumption that adjustments to our behavior and environment can mitigate excess heat-related mortality in the future.

The data shows us that climate change is real, and it is increasingly noticeable in Europe. The medical data also shows us that a higher temperature leads to additional stresses on the body. It stands to reason that this additional stress results in a potential burden for life insurance companies.

Factors other than extreme heat’s direct effects, such as severe weather or spread of disease vectors, merit a deep dive into the role they may play. The evident complexity calls for further research on this topic, including by actuaries. It is clear to me that in addition to efforts to address climate change, adaptations to limit overall risk are urgently required.

This article was initially published by the Society of Actuaries in The Actuary Magazine, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/actuarial-insights-on-heat-related-mortality-and-morbidity/

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). “AR6 Synthesis Report: WGI Figure SPM.3, Table TS.5, Interactive Atlas; WGII Figure SPM.2, WGII SMTS.1, WGII 8.3.1, Figure 8.5; WGIII 2.2.3.” 2023.

- Britannica, Australasia, https://www.britannica.com/place/Australasia

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Sixth Assessment Report, Working Group II – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, “Fact Sheet – Africa,” “Fact Sheet – Asia,” “Fact Sheet – Australasia,” “Fact Sheet – Central and South America,” “Fact Sheet – Europe” and “Fact Sheet – North America.” October 2022. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/about/factsheets/

- World Health Organization (WHO). “Heatwaves.”

- European Center for Disease Prevention and Control. “Factsheet About Seasonal Influenza.” April 12, 2022.

- Ro, Christine. 2022. “Can Japan Really Reach ‘Zero Deaths’ From Heat Stroke?” BMJ 378, no. 2107.

- World Meteorological Organization. “Wildfires Cause Huge Loss of Life in Chile Amid Heatwaves in South America.” February 5, 2024.

- Wiese, Patrick. “Actuarial Weather Extremes Series: 2023 Was the Hottest Year on Record.” Society of Actuaries Research Institute, January 2024.

- Walinski, A., J. Sander, et al. 2023. “The Effects of Climate Change on Mental Health.” Dtsch Arztebl Int 120, Heft 8:120.

- Suran, Melissa. 2023. “Raging Wildfires Are Exposing More People to Smoky Air – Here’s What That Means for Health.” JAMA. Volume 330, Number 14:1311‑1314.

- European Climate and Health Observatory. “Heat.” March 5, 2024.

- Lowen, A.C., S. Mubareka, J. Steel, and P. Palese. 2007. “Influenza Virus Transmission Is Dependent on Relative Humidity and Temperature.” PLoS Pathog 3, no. 10:e151.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). “Climate Change Indicators: Heat-Related Deaths.” November 1, 2023.

- Sheridan, S. C., P. G. Dixon, A.J. Kalkstein, and M. J. Allen. 2021. “Recent Trends in Heat-Related Mortality in the United States: An Update through 2018”. Wea. Climate Soc. 13: 95‑106.

- Sarofim, M.C., S. Saha, M.D. Hawkins, D.M. Mills, J. Hess, R. Horton, P. Kinney, J. Schwartz, and A. St. Juliana. 2016. “Ch. 2: Temperature-Related Death and Illness” in The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, D.C., p. 53. https://health2016.globalchange.gov/low/ClimateHealth2016_02_Temperature_small.pdf

- Gasparrini, Antonio, et al. “Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study.” The lancet 386.9991 (2015): 369‑375.

All endnotes last accessed on 18 June 2024.