-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

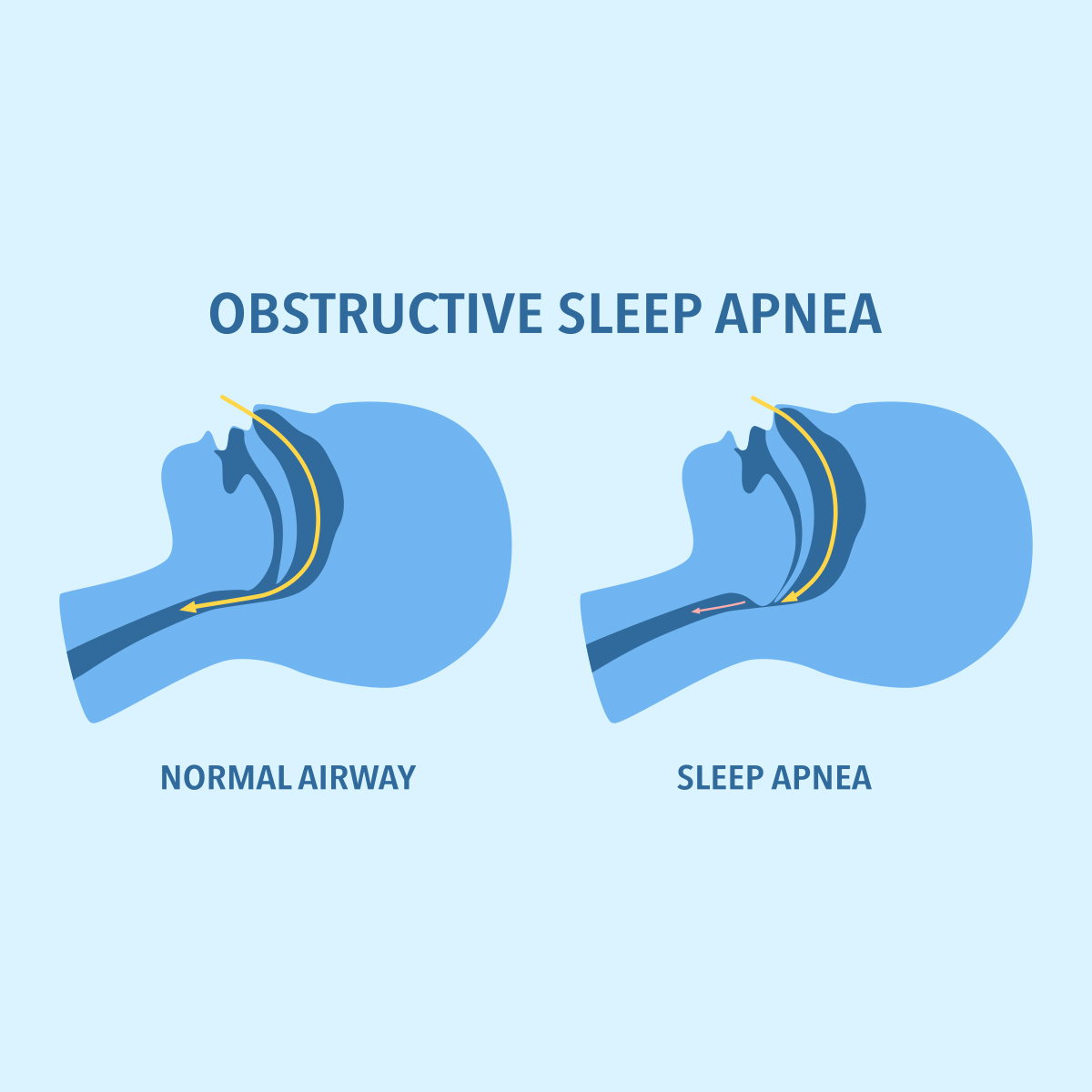

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Knife or Needle: Will the New Weight Loss Medication Replace Bariatric Surgery?

August 20, 2024

Dr. Sandra Mitic

English

Obesity is a highly prevalent, chronic, relapsing disease requiring long-term management. The clinical complications affect almost every organ system, and the impact of obesity on morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs is substantial.

The prevalence of obesity has risen globally in the past decades, a trend predicted to continue. Since 1990, worldwide obesity has more than doubled and even quadrupled in adolescents. The prevalence of adult obesity increased from 31% to 42% between 2000 and 2018 in the U.S.1 Among the 18 European countries with selfreported data available since around 2000, the average obesity rate increased from 11% in 2000 to 17% in 2018.2

In modern societies where food is available in abundance and culturally used as a reward or for comfort, eating has become a dangerous habit and a health threat. Accordingly, losing weight has turned into one of the most important topics in preventing people from obesity-related ill-health. Information about every new way of getting rid of dangerous weight spreads quickly, as do the successes and failures attached to each method. The apparently easier the weight loss, the bigger the hype.

When the glucagon-like peptide‑1 (GLP‑1) analogue semaglutide was approved as an official weight loss medication, it was celebrated on social media as the new game-changer: a simple and effective way to slim down using injections.

This article deals with the effects of GLP‑1 analogues and compares them to bariatric surgery. It explores the future of weight loss and the question of whether the new weight loss medication will replace surgical ways to reduce excess weight.

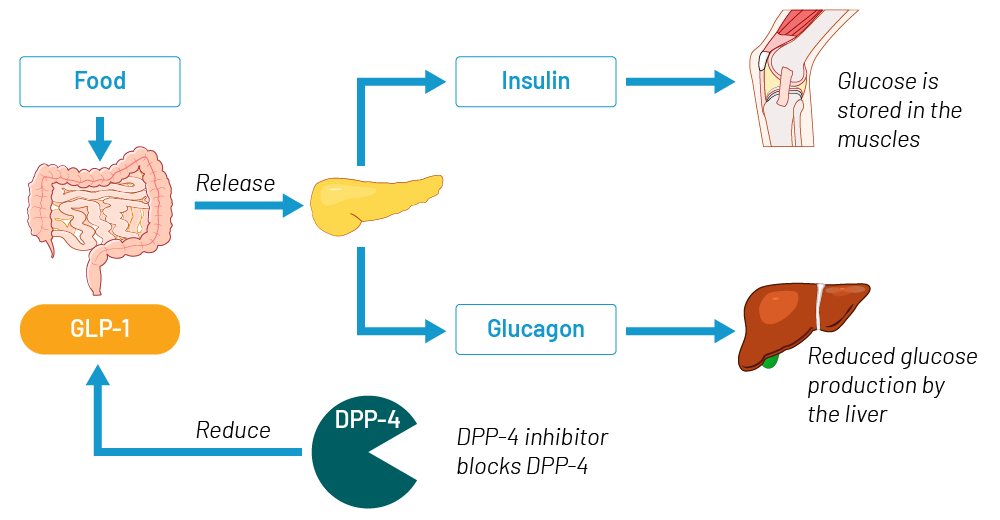

Figure 1 – Biological function of GLP‑1

Source: Gen Re

Glucagon-like peptide‑1 (GLP‑1) is a natural peptide hormone which is produced and secreted by intestinal endocrine cells upon food consumption. It is an incretin that has the ability to decrease blood sugar levels in a glucose-dependent manner by enhancing the secretion of insulin from the pancreas. Glucose is stored in the body muscles and blood levels drop.

GLP‑1 also lowers blood levels of glucagon, the natural antagonist of insulin. The role of glucagon is to increase blood sugar levels by breaking down glycogen in the liver. With lower glucagon levels less glycogen is broken down and less glucose is produced in the liver. When GLP‑1 is released into the bloodstream during food intake, it has a very short half-life: within a few minutes it is broken down by the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP 4) enzyme.

How does the new weight loss medication work?

GLP‑1 analogues work as inhibitors of the enzyme DPP4. The mechanism corresponds to an artificially changed GLP‑1 hormone by slower reduction of GLP‑1, which prolongs its natural glucose-lowering effect. Compared to natural GLP‑1, which has a half-life of only one or two minutes before it is broken down, GLP‑1 analogues have an active phase of several days.

GLP‑1 analogues were originally produced to treat type 2 diabetes. Their effect on weight loss was observed as a positive side-effect when treating people with diabetes. Weight loss is achieved through slower gastric emptying and an additional appetite-suppressing effect of GLP‑1 in the brain.

Other positive effects that were observed in treatment with GLP‑1 analogues were lowering of blood pressure and reduction of C‑reactive protein (CRP) levels. This effect results in the reduction of inflammatory activity, which also seems to have an effect on the atherosclerotic cascade: reduction of arterial inflammation and endothelial dysfunction resulting in reduced arterial stiffness as the main cause for the atherosclerosis.3

There also seem to be positive effects on lipid storage in the liver and a reduction of plasma lipid levels, lowering the risk of lipid storage in the vessels (another promoter of atherosclerosis). Their diuretic effect with excretion of additional fluids results in an improvement of myocardial contractility with positive effects on cardiovascular outcome.4

Not all of these positive cardiovascular effects are yet fully proven or understood. The various effects of GLP‑1 analogues are still under investigation in ongoing studies.

What positive effects of GLP‑1 analogues in obese people without diabetes have been proved so far?

Weight loss: GLP‑1 analogues cause significantly higher weight loss than previously available weight loss medication

This effect was proved in large clinical trials such as STEP, a prospective multi-center randomized controlled trial performed to monitor the semaglutide treatment effect in adults with obesity but without diabetes. Participants were randomly assigned to a group with the weekly application of semaglutide, or a placebo group, and monitored over a period of 104 weeks.

The mean change in body weight was significantly higher (‑15.2%) in the semaglutide group versus (‑2.6%) in the placebo group.5

Other studies have shown similar results in weight loss efficacy. SURMOUNT, an international, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial examined the efficacy and safety of the GLP‑1 analogue tirzepatide in a large group of obese adults without diabetes. Patients were assigned to a weekly subcutaneous application of tirzepatide at one of three doses (5mg, 10mg, or 15mg) or placebo over 72 weeks.

The weight reduction was significantly greater with all three doses of tirzepatide than with placebo (15% to 20.9% weight reduction in 72 weeks versus 3.1% in the placebo group).6

Cardiovascular effects: GLP‑1 analogues show positive effects on cardiovascular risk factors

Some studies focused on the cardiovascular effects of GLP‑1 analogues and on the question of whether a reduction of cardiovascular death could be achieved by treatment.

SELECT, a multi-center, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, event-driven trial enrolled 17,604 patients with pre-existing cardiovascular diseases and a body mass index of 27 or greater but no history of diabetes. Patients were randomly assigned into two group receiving semaglutide or placebo over a mean duration follow‑up of 39.8 ± 9.4 months.

The study showed a lower incidence of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke in the semaglutide group (6.5%) compared to patients treated with a placebo (8%).7

Similar effects were shown in the STEP trial, which observed other effects of semaglutide compared to placebo. The study compared changes in Hb1Ac levels, fasting plasma glucose and fasting insulin. Other factors were lipid levels such as the different forms of cholesterol, triglycerides, free fatty acids and CRP levels.

Improvement could be seen in blood pressure, HbA1c, fasting glucose, fasting serum insulin, CRP and blood lipids after treatment with semaglutide over 104 weeks compared to the placebo group.8

What negative effects of GLP‑1 analogues in obese people have been proved so far?

Like any available medication, GLP‑1 analogues may also have unwanted side-effects. The most common side-effects that can be observed are mild to moderate gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, abdominal pain or dyspepsia.

Other more severe effects occur rarely. Some smaller studies reported about severe to very severe side effects such as gastroparesis, acute pancreatitis, thyroid cancer or even an increased rate of self-harm. So far, no causality linked to the GLP‑1 medication has been proved in any larger studies.

The major risk that has been observed so far is regaining weight after stopping GLP‑1 injections.

STEP 4, a semaglutide withdrawal trial focused on the effects after stopping the weekly injections. All participants started on semaglutide for a period of 20 weeks, showing a mean weight change of ‑10.6%. After 20 weeks, the group was randomly split into a group (A) that continued on semaglutide and a second group (B) that received a placebo instead.

While group A continued losing weight up to a total weight change of ‑17.4% after 68 weeks, group B regained 5.6% of the formerly lost weight, resulting in a total weight loss of 5% after 68 weeks.9

Similar findings were presented in the SURMOUNT 4 trial upon withdrawal of tirzepatide after a treatment period of 36 weeks. The group that continued on tirzepatide for 88 weeks in total showed a mean total weight loss of 25.8%, while the withdrawal group showed a severe regain of weight after continuing on placebo injections.10

How does bariatric surgery work?

Bariatric or metabolic surgery procedures can be grouped into restrictive and malabsorptive surgical techniques. Restrictive techniques, such as gastric banding or sleeve gastrectomy, are based on a temporary or permanent stomach size reduction and restriction of food intake. Malabsorptive techniques reduce the length of the small intestines, leading to reduced absorption of nutrients. They are often combined with the restrictive technique of partial gastric resection to reduce the stomach size, e.g. Roux‑en‑Y gastric bypass, single-anastomosis gastric bypass and biliopancreatic diversion with/without duodenal switch.

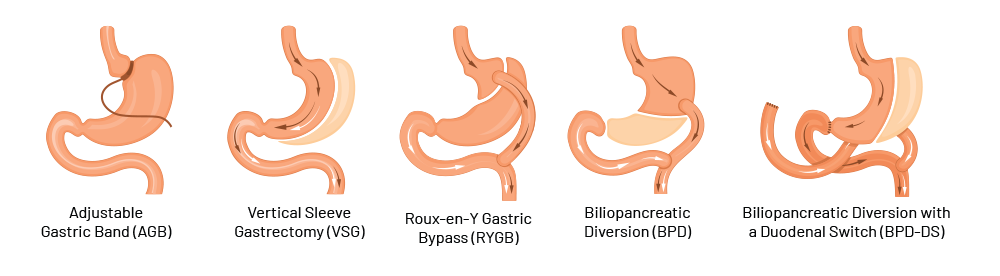

Figure 2 – Different types of bariatric surgery

- Adjustable gastric banding: Placed just below the gastro-esophageal junction and connected to a port that is implanted subcutaneously. By filling of the inner cushion of the gastric band, the inner diameter can be regulated from the outside

- Sleeve gastrectomy: Removal of 80‑90% of the stomach

- Roux‑en‑Y gastric bypass: Formation of a stomach pouch (volume of 20‑30 mL) and direct connection to the small intestine (Y‑Roux technique). Length of the alimentary loop is typically approx. 150 cm, biliopancreatic loop approx. 50 cm

- Biliopancreatic diversion (with duodenal switch): Gastric sleeve, post-pylorical separation of the duodenum, passage reconstruction in Roux‑Y-technique with individual loop lengths. Length of the alimentary loop approx. 250 cm, the common channel 75‑100 cm, biliopancreatic loop several meters

- Single-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB): Gastric pouch with small intestine connected as an omega-shaped loop. Biliopancreatic arm is typically 150‑250 cm long (no illustration)

What positive effects of bariatric surgery in obese people have been proved so far?

Weight loss: different bariatric surgery techniques show significant weight loss compared to previously available non-surgical methods

Bariatric surgery is an established and by multiple large studies approved, effective treatment for morbid obesity. The different procedure results in rapid, pronounced, and sustained weight loss with improved quality of life, and prolonged life expectancy.11

The majority of surgical techniques halve the excess weight or produce a total weight loss of more than 20%. Evidence reports higher weight loss (up to 31% loss of baseline weight) in the first year after surgery, compared to non-surgical matches (1.1% loss of baseline weight). Weight loss is substantial in most patients undergoing surgery.

Ten years after surgery, patients maintain significantly greater weight loss (21.3%) than non-surgical matches (7.3%). In mean excess body weight loss from baseline this is more than 50% compared to non-surgical treatment (8%).12

Malabsorptive bypass techniques seem to be more effective in the long term than single restrictive techniques, which are typically associated with weight regain in around 20% of patients. This effect has been reported by randomized controlled trials comparing outcomes after sleeve gastrectomy and Roux‑Y-gastric bypass operations13,14,15 or in evidence comparing bypass surgery to gastric banding outcomes.16

Cardiovascular effects: bariatric surgery shows positive effects on cardiovascular risk factors

It is widely recognized and evidence-based that any type of bariatric surgery has positive effects on the development of different cardiovascular risk factors. Gastric banding shows a smaller effect on remission of type 2 diabetes than sleeve gastrectomy or bypass surgical procedures.

But all surgical interventions show stronger effects on cardiovascular comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia compared to non-surgical treatment methods of obesity.17

What negative effects of bariatric surgery in obese people have been proved so far?

Surgical procedures have a higher rate of mortality than medication, although the mortality rate in bariatric surgery has declined. Well-established international guidelines with detailed recommendations on pre‑, intra- and postsurgical monitoring of patients have helped to reduce surgical morbidity and mortality rates.

However, bariatric surgery still presents a risk for developing different types of complications, distinguished between early and late onset of complications.

- Early complications of bariatric surgery: the most frequent complications are anastomotic leaks, stenoses or loop kinking, postsurgical bleeding or thromboembolic events.

An anastomotic leak is the most dreaded complication of any bariatric procedure because it increases overall morbidity to 61% and mortality to 15%. Failure of anastomosis can result in gastroenteric fistulae, which may take months to resolve. Patients with a body mass index of >50 kg/m², and those with dysmetabolic syndrome are most at risk for leaks.

The incidence of stenosis, kinking or twisted intestinal loops is especially high in surgical procedures with gastroenteric anastomoses, such as in Roux‑Y gastric bypass surgery where it is up to 19%.

Postsurgical bleeding that requires intervention occurs in up to 11% of cases in both bypass or sleeve gastrectomy; 85% of bleeds are likely to stop without surgical intervention.

The risk of a venous thromboembolism after bariatric operation is low, but a pulmonary embolism is still the most common cause of mortality after these procedures.

Slippage is considered the most common complication after laparoscopic adjustable gastric band and occurs in 8% of patients.18,19 - Late complications of bariatric surgery: a considerable proportion of patients experience side-effects, which often manifest many years after the procedure, including various gastrointestinal disorders and need for endoscopic or surgical reinterventions, e.g. because of internal hernias and anastomotic ulcers.

Malabsorption of nutrients or endocrine dysregulation can cause health problems after bariatric surgery.

In gastric bypass surgery, most of the stomach and the first portion of the small bowel are disconnected from the passage of food, frequently resulting in malabsorption of essential substances absorbed in these parts of the gastrointestinal tract, including iron, calcium, folic acid, vitamin A, vitamin B1, vitamin B12, and vitamin D.

Although many patients are routinely put on supplements in order to avoid deficiencies after surgery, nutritional disorders are five times more common in patients who have undergone bariatric surgery than in patients following non-surgical weight-loss methods.

Long-term data from a recent observational study indicate that the risk of manifest anemia owing to iron or vitamin B12 deficiency is increased almost three-fold after bariatric surgery.

Rapid weight loss and malabsorption of calcium and vitamin D can lead to reductions in bone mineral density, which might result in osteoporosis and increased risk of bone fractures.20,21

A very specific complication of bypass surgery is the “dumping” syndrome. Bariatric bypass surgeries lead to unphysiologically rapid transit of recently ingested food to the small bowel. Undigested carbohydrates might cause late dumping effects, characterized by symptoms of low blood sugar levels (hypoglycemia) one to three hours after a meal. Late dumping occurs in more than 20% of patients after gastric bypass. Dumping effects rarely develop earlier than six months after surgery.

Late dumping can often be managed with dietary changes, such as a diet low in carbohydrates and rich in protein and fiber, reduced portion sizes, and lying down after a meal to slow down the initial food passage. Patients with refractory late dumping might require longstanding medication or, as a last resort, reversal of the gastric bypass.22,23

Will GLP‑1 analogues replace bariatric surgery in the future?

Based on currently available evidence, bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for severe obesity, with the risk of (post‑)surgical complications. The weight loss effect of GLP‑1 analogues without having to undergo surgery and with the possibility of immediate cessation of treatment if side-effects occur, seems like a promising alternative. But it remains unclear which treatment has better effectiveness in terms of sustainable weight loss and reduction of cardiovascular risks.

Single studies are comparing bariatric surgery results to GLP‑1 analogues. Some report that surgery is associated with greater weight loss and greater reduction of mortality. One study showed a lower mortality risk in people with an underlying diabetes diagnosis duration of 10 years or less and underwent bariatric surgery compared to a group that was treated with GLP‑1 analogues. No differences in mortality risk or major adverse cardiovascular events could be observed among individuals with a longer duration of diabetes.24 However large studies comparing positive effects on weight loss or cardiovascular risk factors with the new generation of GLP‑1 analogues such as semaglutide or tirzepatide to bariatric surgery are lacking.

Combining the new weight loss medication with bariatric surgery seems like a possible treatment option for obesity. According to the American Society for Metabolic or Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) in its 2024 annual scientific meeting, the risk of complications from metabolic surgery for very obese people may be reduced by taking GLP‑1 drugs before bariatric surgery.25 Currently no evidence from large trails on this hypothesis is available.

It is conceivable that the new medication could reach people who would not consider surgical treatment. It remains to be seen whether the trend of presumably lifelong medication with GLP‑1 analogues to maintain the effect of weight loss will prevail over surgical interventions, which could possibly have a lifelong effect but with the risk of complications.

It can be assumed that both types of treatment will probably continue and co‑exist. In the spirit of personalized medicine and depending on the conditions of the existing healthcare system, both options will be used successfully and individually in the future.

The insurance industry should be aware that new weight loss treatments are available and monitor the long-term effects and sustainability of the different treatments reported in medical evidence. For the different types of weight loss, different risk assessments may have to be assumed at the time of underwriting.

- World Health Organization, Obesity and overweight, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- OECD/European Union (2020), Health at a Glance: Europe 2020: State of Health in the EU Cycle, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/82129230-en

- Boyle JG, Livingstone R, Petrie JR. Cardiovascular benefits of GLP‑1 agonists in type 2 diabetes: a comparative review. Clin Sci (Lond). 2018 Aug 16;132(15):1699–1709. doi: 10.1042/CS20171299. PMID: 30115742

- Ibid

- Garvey WT, Batterham RL, et al. Two-year effects of semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity: The STEP 5 trial. Nature Medicine. Vol 28; Oct 29222; 2083‑2091

- Jastreboff AM, et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:205‑216. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206038. VOL. 387 NO. 3

- Lincoff AM, et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:2221–2232. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2307563. VOL. 389 NO. 24

- Garvey WT, Batterham RL, et al. Two-year effects of semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity: The STEP 5 trial. Nature Medicine. Vol 28; Oct 29222; 2083‑2091

- Rubino et al. & STEP 4 Investigators (2021). Effect of Continued Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo on Weight Loss Maintenance in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 325(14), 1414‑1425. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.3224

- Aronne et al. & SURMOUNT‑4 Investigators (2024). Continued Treatment With Tirzepatide for Maintenance of Weight Reduction in Adults With Obesity: The SURMOUNT‑4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 331(1), 38‑48. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.24945

- Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes 12 years after gastric bypass. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1143‑1155

- Maciejewski ML, et al. Bariatric Surgery and Long-term Durability of Weight Loss. JAMA Surg. 2016 November 1; 151(11): 1046‑1055. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2317

- Wölnerhanssen BK, Peterli R, Hurme S, et al. Laparoscopic Roux‑en‑Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: 5‑year outcomes of merged data from two randomized clinical trials (SLEEVEPASS and SM‑BOSS). Br J Surg. 2021 Jan 27;108(1):49‑57. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znaa011. PMID: 33640917

- Sharples AJ, Mahawar K. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials Comparing Long-Term Outcomes of Roux‑En‑Y Gastric Bypass and Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2020 Feb;30(2):664‑672. doi: 10.1007/s11695‑019‑04235‑2. PMID: 31724116

- Grönroos S, Helmiö M, Juuti A, et al. Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Roux‑en‑Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss and Quality of Life at 7 Years in Patients With Morbid Obesity: The SLEEVEPASS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2021 Feb 1;156(2):137‑146. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5666. PMID: 33295955; PMCID: PMC7726698

- Nguyen NT, Kim E, Vu S, et al. Ten-year Outcomes of a Prospective Randomized Trial of Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass Versus Laparoscopic Gastric Banding. Ann Surg. 2018 Jul;268(1):106‑113. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002348. PMID: 28692476; PMCID: PMC5867269

- Ding L, Fan Y, Li H, et al. Comparative effectiveness of bariatric surgeries in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2020 Aug;21(8):e13030. doi: 10.1111/obr.13030. Epub 2020 Apr 14. PMID: 32286011; PMCID: PMC7379237

- Lim R, Beekley A, Johnson DC, et al. Early and late complications of bariatric operation. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018 Oct 9;3(1):e000219. doi: 10.1136/tsaco‑2018‑000219. PMID: 30402562; PMCID: PMC6203132

- National Library of Medicine, Skogar ML, Sundbom M. Early complications, long-term adverse events, and quality of life after duodenal switch and gastric bypass in a matched national cohort. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32156633/

- Parrott J, Frank L, Rabena R, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery integrated health nutritional guidelines for the surgical weight loss patient 2016 update: micronutrients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017; 13: 727‑41

- Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, et al. Weight and Metabolic Outcomes 12 Years after Gastric Bypass. N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 21, 377:1143‑1155

- Fayad L, Schweitzer M, Raad M, et al. A real-world, insurance-based algorithm using the two-fold running suture technique for transoral outlet reduction for weight regain and dumping syndrome after Roux‑En‑Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2019; 29: 2225‑32

- Lassailly G, et al. Bariatric Surgery Reduces Features of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Morbidly Obese Patients. Baillières Clin Gastroenterol. 2015, 149:379‑388

- Dicker D, Sagy YW, Ramot N, et al. Bariatric Metabolic Surgery vs Glucagon-Like Peptide‑1 Receptor Agonists and Mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6):e2415392. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15392

- ASMBS 2024, Pre-operative use Of GLP‑1s May Reduce Complications After Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery in Patients with Extreme Obesity https://asmbs.org/news_releases/pre-operative-use-of-glp-1s-may-reduce-complications-after-metabolic-and-bariatric-surgery-in-patients-with-extreme-obesity

All endnotes last accessed on 2 August 2024.