-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

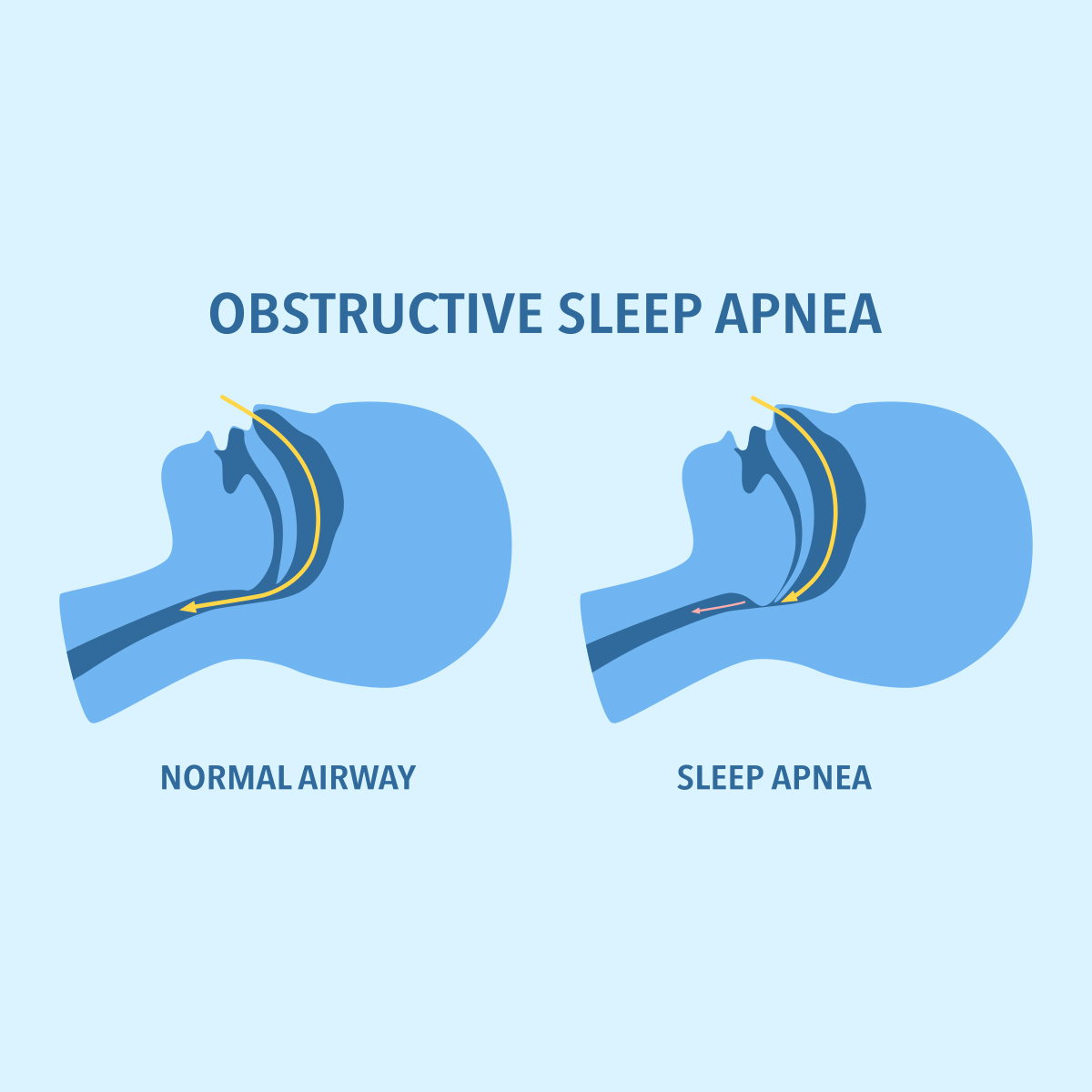

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

An Actuarial Obituary for the “Optimist”

June 22, 2022

Beata Puls,

Sara Goldberg

English

Deutsch

U.S.-born demographer James W. Vaupel passed away this spring. The field of gerontology may not be the liveliest of disciplines when it comes to celebrity, but Professor Vaupel is as much a household name as any.

Life expectancy is a lot about averages, and he was not an average man. He managed a multidimensional, spectacular career. His research delved into frailty models and the heterogeneity of longevity.1 First a public policy teacher at Duke University, known for being a charismatic and inspiring lecturer,2 and briefly consultant to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, he went on to become founding director of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in 1996.

One of his more recent contributions was to systematically collate oldest-old (105+) registry data internationally through the International Database on Longevity,3 where validation processes are undertaken to derive a data basis to estimate mortality trajectories at highest ages. Professor Vaupel was an advocate of open-sourcing demographic knowledge through projects such as MaxNetAging. He was awarded membership to the National Academy of Sciences and was a fellow of the American Academy of Sciences and of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina.

He remained active in his research and mentoring other researchers until, after a short illness, he passed away suddenly, having attained 76.9 years. Although he led a relatively private life, his excellent professional contributions have led to a wall of gratitude, one gleans from comments left behind.4 Descriptions centre around his generosity, magnetic personality, and a good laugh, according to the remembrances – as they say, laughter is the best medicine (and a predictor of longevity: we give a strong sense of humour a +3.14159 on our longevity tables to the extent we are able to underwrite for that).5

“Everyone” knows that the life expectancy of American men is just about 77, and in Denmark (where Professor Vaupel lived for a significant time and whose Queen knighted him for his research contributions to the University of Southern Denmark), it is higher, at 80. So arguably he fell a bit short, having attained 76.9 years. How did this happen?

First of all, “every” actuary knows to look at periodic tables to look at historical life expectancy. So when one combines period tables – and this is where this contribution waxes a bit nerdy – we can estimate his population-based life expectancy a bit more accurately. Merging period life tables to create a generational life table for American men born in 1945 would yield a life expectancy of a more modest 72.0.

This raises an interesting question – which tables to use? Danish, German, or American? Does one’s ethnicity account for national differences in life expectancy, or the environment?6

A U.S. population is arguably arbitrary for a man with European roots generations ago who then returned to Europe. Born in New York, Professor Vaupel travelled and resided in northern Germany from the 1990s and “periodically” in Denmark, finally resettling there at age 68. The diligent longeval registries kept in Denmark and other Nordic countries attracted him to Denmark and kept him there, ultimately settling with his wife and two children.7

In the cases of the U.S., Denmark, and Germany, this is a matter of splitting hairs, since the period life tables are similar at the relevant ages, but nonetheless applying a blend of those residences yields an individual cohort life expectancy of 71.9.8

Prospective life tables accounting for mortality improvements in forecast years would have yielded 72.2, still materially lower than the actual achieved 76.9.

An individual life

It’s a somewhat more subjective argument, but how should one think about individual life expectancy? Why may it come as a shock that someone such as Professor Vaupel does not make it to his 80s? The “whole community of demographers [were left] stunned.”9

Perhaps it is because time starts “ticking” only once a public figure is on the map – meaning having entered the international public sphere, which for Professor Vaupel was at latest the news of international prizes streamed in during the early 2000s, including admission as a regular scientific member to the National Academy of Sciences in 2004. This would have put his conditional projected life expectancy just to over 82.

Also, genetics should count for something: his father and mother lived to an impressive 90 and 96 respectively, yet his sister passed away at 64 of cancer.10 In fact, Professor Vaupel had something to say about the genetic contribution to longevity, having been a trailblazer in separated twin studies in Nordic countries. According to his own study of Danish twins he put the genetic contribution to one’s predicted life span at 25%.11

Known to actuaries as the optimist sky’s-the-limit in future life expectancy, Professor Vaupel was publicly pitted against Professor Jay Olshansky – a founding director of Lapetus Solutions Inc., University of Chicago professor, as well as known historically for arguing towards a fixed life expectancy – in arguing against senescence. The truth may be somewhere in between, where a plethora of studies and data points serve to support both rectangularisation and life extension at the oldest-old.12

While we have had a global life expectancy setback with COVID-19, perhaps the latest developments tilt in Professor Vaupel’s favour, where science and technology will continue to deliver efforts from mRNA technology to safer stem cell research in mice at Harvard Medical School and many other laboratories.13

Coincidentally, optimism per se should also increase life expectancy.14, 15

What else should we consider in squaring Professor Vaupel’s actual life span against our default mortality tables?

- Socioeconomically advantaged, having a doctorate from Harvard: +5

- Working three jobs, stress factor: -1

- Do spousal habits of Danish women, known prevalent smokers, rub off? -0 (unproven)

- Mortality expert, presumably with knowledge of life-extending behaviours and awareness of healthy habits: +5

Of course, such post-mortem adjustments are symbolic and not accurately derived, but in sum, we do not arrive at 76.9. The adjusted life expectancy should perhaps have been longer than the life he led, but as we know – mortality is full of volatility and injustice.

Whatever the appropriate post-mortem calculations are is moot, but the world of longevity and demography will miss Professor Vaupel’s wisdom and voice, and his legacy to the field will surely last (forgive our optimism) into supercentenarian territory.16 Hence we say: long live optimism.

Endnotes

- http://www.nasonline.org/member-directory/members/3006987.html

- https://sanford.duke.edu/story/remembering-james-vaupel-one-dukes-first-public-policy-professors/

- https://www.supercentenarians.org/en/

- https://remembering-james-vaupel.org/

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/laugh-lots-live-longer/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4029590/

- https://www.sdu.dk/en/forskning/forskningsenheder/samf/cpop/remembering_james_vaupel/obituary_kristensen_holm_jeune

- Derived from mortality tables from Human Mortality Database, https://www.mortality.org/

- https://genus.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41118-022-00163-9

- https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Vaupel-66 and https://www.demogr.mpg.de/mediacms/1347_main_Trauerrede_Nancy_Vaupel_15112011.pdf

- https://user.demogr.mpg.de/jwv/pdf/Vaupel-HG-97-1996-3.pdf

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1047279716300072#fig2

- https://edition.cnn.com/2022/06/02/health/reverse-aging-life-itself-scn-wellness/index.html

- https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/press-releases/optimism-longevity-women/

- https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/working-paper-117_optimism-and-life-expectancy_oconnor_graham.pdf

- IDL, ibid.

All endnotes last accessed on 21 June 2022.