-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Remember to Forget – Insuring Cancer Survivors and the Right to be Forgotten

In February 2021, the European Commission (EC) published “Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan”, which sets out an action plan to fight cancer in the European Union (EU). In addition to steps for the prevention and treatment of cancer, this also includes ensuring the quality of life of cancer patients and survivors.

Part I: Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan & the Right to be Forgotten

Explicit reference is made to the access to financial services, which – in the case of Life insurance – is claimed to be made more difficult by declining coverage or by greatly increased insurance premiums for cancer survivors, even if the cancer has been in remission for a long time. The EC therefore introduced the “Right to be Forgotten” (RTBF), which is intended to ensure that former cancer patients who have successfully overcome their illness do not experience adversities when taking out necessary insurance policies.1

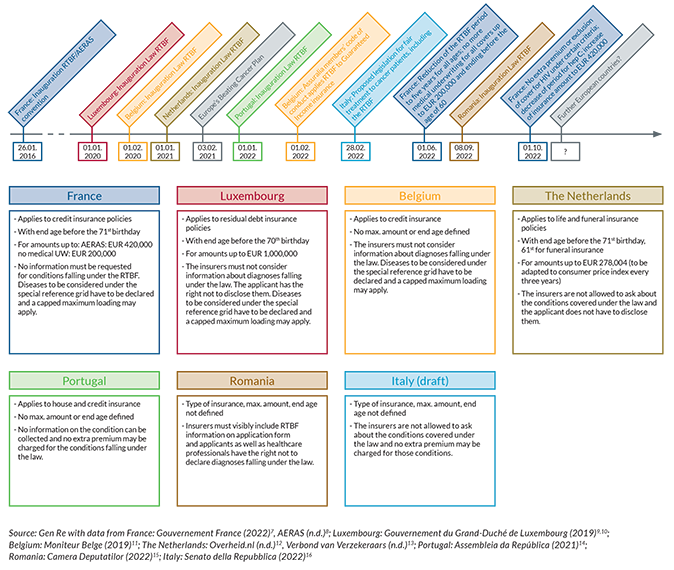

A few European countries have already implemented such a RTBF. In France it has been effective since 2016; in 2020 and 2021 it came into force in Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. In the beginning of 2022, Portugal implemented corresponding legislation; Romania has followed suit in September 2022 and in Italy a proposed legislation was presented to the senate that also includes adoption rights for cancer survivors.2 Figures 1 and 2 provide an overview on the RTBF legislations in different EU countries.

The EC’s action plan now calls on all EU countries to work together to implement the Beating Cancer Plan. We therefore expect that more (European) countries will be urged to consider such a RTBF and work on its implementation in a timely manner.

The RTBF states that insurers, when calculating insurance premiums, may not consider medical information on cancers that occurred more than a defined period, usually five or 10 years — not after diagnosis but after the completion of the therapeutic protocol without recurrence.

The law is intended to ensure the quality of life of a cancer survivor by ensuring access to necessary basic insurance services. While there is no legal obligation to secure Life insurance when taking out a loan, it is considered common practice for banks and credit providers to grant loans only when such insurance is obtained.3,4,5,6

To target the law to this particular population and essential financial services, the initial RTBF legislations had a narrow scope applying to certain types of Life insurance only, with additional restrictions addressing maximum insurance amounts and age ranges (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Right to be Forgotten across the EU

Types of insurance covers, sums assured and differences in declaration (last update 1 October 2022)

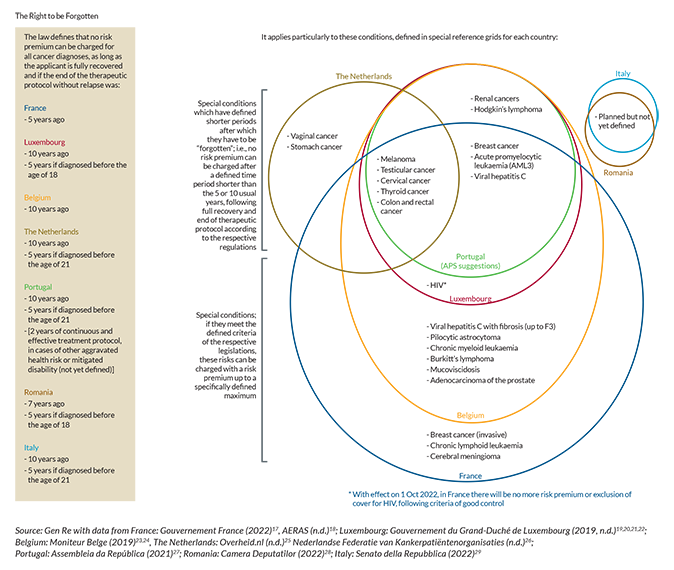

For certain cancers that have a particularly good prognosis and a low risk of recurrence, special shortened cut-off times apply. In addition, other chronic diseases are often listed that may not be considered or may be rated only with a fixed maximum additional premium. These include, above all, hepatitis C and HIV. These distinct conditions are defined in so-called reference grids that differ slightly in each country and legislation (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Comparison of the RTBF legislation in different EU countries

Time periods of RTBF application and diseases with special conditions (last update 1 October 2022)

Portugal is a special case

The other European countries that have implemented the RTBF have a reference grid showing special conditions that fall within the law. On one hand these include less severe cancers which have better prognoses and can therefore be considered resolved after a shorter period after the end of treatment. On the other hand, they also define criteria and maximum loadings for other chronic conditions, such as hepatitis C, HIV or leukaemia.

Even though the Portuguese law specifically includes chronic diseases (no information can be collected after two uninterrupted years of efficient treatment in case of aggravated health risk or mitigated disability), there is not yet such a reference grid to guide insurers in applying the law.

The Portuguese Association of Insurers (APS) has created a suggested table for the more benign cancers and viral hepatitis C, following the example of Luxembourg and Belgium, but it remains unclear how to treat other conditions such as diabetes and HIV, resulting in confusion for applicants and the insurance companies.

Recent developments

While the first initiations of the law have been relatively clear-cut and limited, recent advances have been more far-reaching. Even though it is not clearly defined how the law is to be applied, the Portuguese version includes the right to forget chronic illnesses following “effective and continuous treatment for two years”.

With effect of 1 October 2022, the French legislation treats HIV not with a restricted maximum loading, but rather includes it in the non-rateable conditions that will have to be forgotten entirely if the necessary criteria are met.30 Earlier this year, in France the period after which conditions have to be forgotten has been reduced to a maximum of five years for all ages; and medical underwriting for loan insurance with sums assured up to EUR 200,000 has been abolished altogether.31

The Belgian insurance association, Assuralia, has obliged its members to a code of conduct that additionally applies the RTBF to Guaranteed Income insurance, a Disability insurance that pays out in case of prolonged illness or disability to compensate for the difference between the normal salary and the public social security system.32

With these developments and the foreseeable implementation of the law in further countries, we want to comment and discuss the implications of the law for the insurance industry and create a basis for a joint dialogue between representatives from politics, patient groups and insurance that will make it possible to find consensual regulation in countries that are planning to implement the RTBF, or in countries that plan to extend the current legislation.

In order to estimate the risk that insurers will be exposed to with the RTBF, we will in the following provide an overview on cancer risk in general, with a focus on long-term mortality risk and on how the RTBF may affect an insurer’s portfolio.

Part II: Long-term risk of cancer

The number of cancer survivors is increasing

The number of people living after a cancer diagnosis (i. e. prevalent cases) has been increasing for the past 30 years, reaching around 5 % of the total population in several countries.33 This trend is driven by an increasing number of new cancer diagnoses (predominantly due to population ageing) and by improving cancer survival rates associated with better treatment and early diagnosis.

In 2020, there were around 20 million cancer survivors in Europe and about one-third of these are within working age and thus potential candidates to buy insurance cover.34 This growing group of people includes cancer patients who are currently in treatment, patients who are in remission, i. e. who have become cancer‐free but still have a measurable excess risk of recurrence or death, and patients who are considered to be “cured”, as they have reached the same mortality rates as the general population.35

Within the scope of the RTBF, all types of cancer will be accepted at standard rates five or 10 years after concluding treatment. How will the RTBF influence the insurer’s portfolio when risk adjustment measures are no longer possible or permitted only for certain types of insurance covers? Do cancer survivors have significant extra mortality if they have been cancer-free for 10 years and more?

In the following, we will try to give some answers to these questions. First, let us look into medical studies on cancer survival.

Cancer survival depends on different factors

An individual’s life expectancy and survival after a cancer diagnosis is dependent on the age at diagnosis, the type of cancer that was diagnosed, the stage at which the cancer was diagnosed and the type of treatment that the patient received. Consequently, there is a huge variability in cancer survival.

Not only the “cure fraction”, i. e. “the proportion of cancer cases expected to reach the same death rates of the general population” differs between cancer types, but also the “time-to-cure”, defined as the “number of years after cancer diagnosis necessary to eliminate or to make the excess mortality due to cancer negligible”.36

Cancers with a very good prognosis and a short time‑to‑cure

There are several cancer types that, when diagnosed at an early stage, have a particularly good prognosis and a short time-to-cure, for example testicular and thyroid cancers with a cure fraction of 94 % and 98 %, respectively, and a time-to-cure of less than one year after diagnosis.37

Cancers in this group can today be seen as chronic diseases rather than a death sentence and it is therefore legitimate to “forget” them at an earlier stage as defined in the RTBF’s medical grids.

Cancers with a negligible long-term risk

Another group of cancers has been identified, for which the cancer-related “excess mortality became negligible in less than 10 years for patients below 45 years of age with Hodgkin lymphoma, skin melanoma, and cervical cancer”.38 Furthermore, a “negligible excess risk of death within 10 years from diagnosis” has been reported for colorectal cancer patients and younger patients with stomach cancer.39

These cancers do not seem to have a significantly increased mortality after 10 years compared to the general population and it should therefore be legitimate to “forget” them 10 years after concluding treatment.

Cancers that come back many years after diagnosis

There are cancers which have a risk of late recurrence or death even 10 years after diagnosis, e. g. lung cancer with a time-to-cure of more than 10 years, breast cancer with a time-to-cure of 10 to 17 years, or bladder cancer with a time-to-cure of 18 to 20 years.40,41

This group of cancers is relevant for the insurers in the scope of the RTBF as the cancer-related mortality is still elevated 10 years after diagnosis.

Long-term risks of cancer treatment

Cancer treatment is getting more precise, resulting in higher survival rates and less severe long-term effects for cancer survivors. Despite this favourable development, cancer treatment can still be harmful to the body, and cancer survivors can, depending on their treatment, be more prone to develop second cancers and other chronic conditions, including defects of their thyroid gland, diabetes, neurological complications, liver failure, renal disease and heart failure.42

While in older adults (diagnosed at ages 60 to 70), the “negative long-term effects of cancer treatment could eventually be reduced to a minimum”43 long-term effects of cancer treatment seem relevant for childhood cancer survivors. A recent study examined late effects in children and young adults who had a cancer diagnosis before the age of 25 years and were followed for 20 years. The study summarises that “cancer survivors are a heterogeneous group where the extent of late effects differs across cancer subtypes, deprivation status, treatment exposures and chemotherapy drug classes. Compared with community controls, survivors notably had a higher risk of morbidity regardless of their primary cancer diagnosis and deprivation status.”44

This is relevant for the RTBF population as the 10 years will have passed when this age group reaches the typical age of applying for Life insurance in association with a mortgage. Late effects of cancer treatment can still be underwritten in the RTBF, but the original cancer cannot. This is a challenge that is present in underwriters’ daily work in countries where the RTBF already is in force.

Long-term mortality of all cancers combined

The RTBF will not distinguish between different cancer types or cancer stages after a certain time period following the treatment. What is the real long-term mortality risk when we look at all cancers combined?

a) Literature research

There are a few recent studies that evaluate “all cancer” survival or mortality. The authors of an Italian study on cancer patients aged 45 to 80 who were followed for 28 years after their diagnosis conclude that “cancer patients’ life expectancy in the long-term approaches, but seldom reaches, the general population’s life expectancy”.45

Another study on Swedish cancer patients diagnosed at age 60 and followed for 17 years after diagnosis, showed that cancer patients had increased mortality rates compared to the total population in the years after diagnosis. This converged towards the mortality level of the total population five to 10 years after diagnosis, but still did not reach the level of the total population 17 years after diagnosis.46

The elevated mortality of cancer survivors in the long term can be attributed to cancer relapse, second cancers and late effects of cancer treatment.47,48 Furthermore, when lifestyle behaviours that may have contributed to the development of cancer persist (such as smoking and unhealthy diet), these can continue to decrease a patient’s survival in the long term.49,50

However, the cancer-related extra mortality was not quantified in the publications, and to estimate the risk that insurers will be exposed to in the scope of the RTBF, we analysed data from the U. S. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Cancer Registries Program (2000–2018).51

b) Actuarial considerations: calculation of cancer patients’ relative mortality one to 18 years after diagnosis

In order to estimate the mortality risk of all cancers combined, we extracted mortality data from the SEER database for cancer patients diagnosed in the years 2000 to 2018.52 The relative mortality of cancer patients was calculated as the ratio of the “observed mortality” of cancer patients to the “expected mortality” of the general population, which provides a measure of the excess mortality experienced by cancer patients.

Statistical analysis was performed using the software “R” and a GLM framework with Tukey Test. A Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was applied to determine significances. More details on data extraction methods and statistical analyses are available upon request.

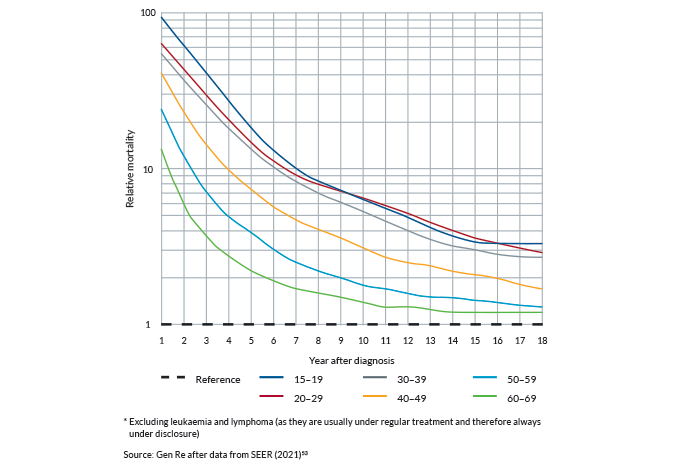

Relative mortalities for different age bands are shown in Figure 3, as per years after diagnosis. Please note that the x‑axis shows the years after diagnosis and not the years after the end of treatment (which applies to the RTBF). If we suppose that cancer treatment takes around two years, we have to look at the time points seven and 12 years after diagnosis to indicate the time points five and 10 years after finishing treatment, which are relevant for the RTBF.

Figure 3: Relative mortality of all cancer sites combined*

Log-normal y‑axis; 1‑18 years after diagnosis for different age bands. Relative mortality indicates the excess mortality of cancer patients as a factor to the population mortality (dashed line)

Relative mortality is decreasing one to 18 years after diagnosis

The SEER data in Figure 3 show that the relative mortality of cancer patients is highest in the first year after diagnosis and falls sharply thereafter but remains above population mortality.55 The highest decrease in relative mortality is observed one to five years after diagnosis and there is a continued decrease in the relative mortality five to 18 years after diagnosis.

Younger ages have a higher relative mortality compared to older ages

The relative mortality is significantly higher in younger age groups compared to older age groups over the course of 18 years after diagnosis. Cancer patients aged < 30 years had a significantly higher relative mortality compared to patients aged 50 to 69 years; and cancer patients aged 30 to 39 years had a significantly higher relative mortality compared to patients aged 60 to 69 years.

Within 10 and 15 years after cancer diagnosis, the relative mortality gap between the different age groups becomes much smaller, as opposed to the earlier years after diagnosis, but is still significantly different between all age groups, except between age bands 50 to 59 and 60 to 69 years. The excess mortality that is observed in the age bands 15 to 20 years is particularly relevant for the RTBF, as for childhood cancer survivors, a previous cancer diagnosis is already “forgotten” within five years after treatment.

Cancer patients’ mortality is higher than the general population’s mortality even 10 to 18 years after diagnosis

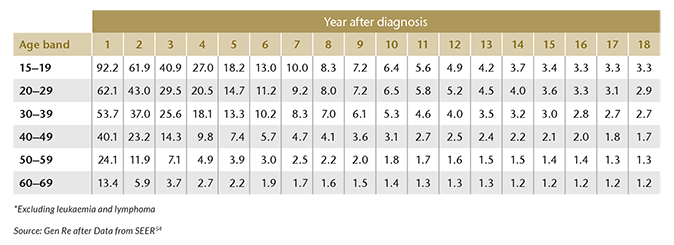

The SEER data show that mortality in cancer survivors is still higher compared to the general population 10 to 18 years after diagnosis. The corresponding numbers in Table 1 show the x‑fold increase in mortality of the cancer population, as compared to the general population.56

Table 1: Relative mortality of all cancer sites combined*

1‑18 years after diagnosis for different age bands. Relative mortality indicates the excess mortality of cancer patients as a factor to the population mortality.

For example, 12 years after diagnosis, cancer patients aged 30 to 39 years have a 4‑fold increased mortality compared to the general population, and a 2.7‑fold increase is still present 18 years after dignosis.

Older age bands (50 to 70 years) approach the population’s mortality more quickly than younger age bands: patients aged 60 to 69 years have only a 1.6‑fold increase in mortality already eight years after diagnosis, which decreases to a 1.2‑fold increase 14 years after diagnosis and remains at that level until 18 years after diagnosis.

It should be noted that the general population mortality level includes individuals who died due to cancer, and cancer is among the top two leading causes of death in the U.S. for both men and women aged 45+.

Conclusions

- There is still excess mortality in the cancer population 10 to 18 years after diagnosis, when the RTBF will apply for patients that are older than 25 years.

- The ages between 50 and 70 years approach the mortality of the total population more quickly than the ages between 15 and 50 years, but the mortality level of the total population is still not completely reached 18 years after diagnosis for either of the age bands.

- The excess mortality is higher in younger cancer patients compared to older cancer patients.

To get a European perspective, we compared the U.S. SEER data to mortality data derived from the German cancer registry57 and we observed a high level of consensus (data not shown, available upon request).

Part III: Considerations on the RTBF population

In countries where the RTBF is already in force, it is limited to mortgage and loan covers and additionally, there is often a limitation of the end age. Consequently, the group of people who can benefit from the RTBF at the current stage is very specific.

In the following, we will describe the RTBF population, based on the assumption that the RTBF is limited to mortgage and loan covers.

Which age groups are relevant for the RTBF population?

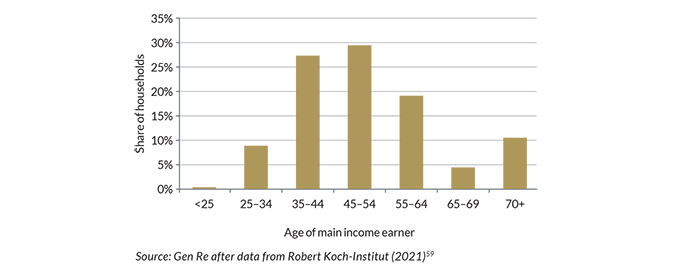

To answer this question, it is worthwhile to investigate at which ages people take out mortgage loans. Figure 4 shows the share of private households with a residual mortgage debt by the age of the main income earner as of 2013.58 Note that the data indicate the residual mortgage debt, so the application for the mortgage loan happened a few or many years earlier.

Figure 4: Share of private households with a residual mortgage debt by the age of the main income earner as of 2013

Assuming similar behaviour of the consumers of mortgage covers, the dominant age group for the RTBF would roughly be between 25 and 65 years with a peak between 35 and 50 years. The RTBF is not applicable from age 70 onwards in many countries, so the ages between 60 and 70 will be under disclosure within the RTBF.

In conclusion, we assume that the age group of interest for the RTBF applicants lies between 25 and 60 years.

So, the next question is:

How many people within the relevant age group may have had a cancer diagnosis?

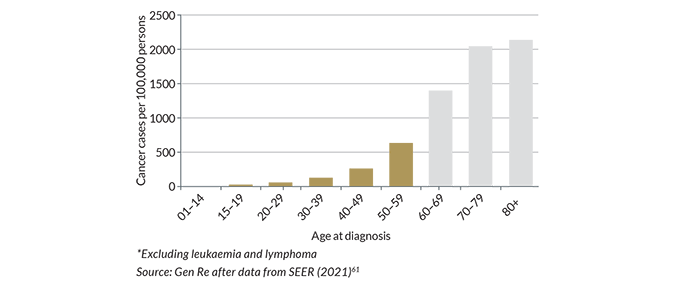

In order to answer this question, we need to look at the “incidence rate”, which provides the number of people that are diagnosed with cancer at a certain age. In Figure 5, we can see the “all cancer” incidence rate from the SEER data60 with the relevant age group for the RTBF highlighted in grey.

Figure 5: Cancer incidence rate of all cancer sites combined*

The relevant age group for the RTBF highlighted in olive. By age at diagnosis, diagnosed in 2000‑2018

Cancer incidence rates increase with age, especially steeply in people that are older than 60 years. In the age groups of interest for the RTBF (people < 60 years), cancer diagnoses account for only 16 % of all cancer cases.

As a conclusion, the RTBF will affect only a small proportion of all cancer cases.

Conclusion on cancer mortality, cancer incidence and the RTBF population

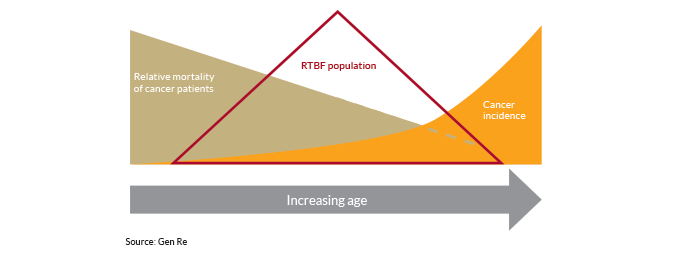

The findings from above can be visualised in Figure 6, a model that combines the three aspects: relative mortality, cancer incidence and the identified RTBF population in relation to increasing age.

Figure 6: The effect of increasing age on relative mortality of cancer patients (beige), cancer incidence rates (orange) and the identified RTBF population (red)

Younger individuals (aged < 25 years) have a higher relative mortality after a cancer diagnosis, but will be accepted at standard rates already five years after the end of treatment. At the same time, very few cancers are diagnosed at these very young ages so the population with this high risk that is likely to apply for insurance cover is rather small.

At higher ages (> 50 years), the relative mortality after a cancer diagnosis is lower compared to younger ages, but in this group, the cancer incidence is already rising. So, the relatively low mortality will be relevant for the insurers’ portfolios because of the larger number of cancer cases. What mitigates this risk is that the above identified RTBF population lies within the age group below 60 years and therefore, the effect of the rising cancer incidence and the associated risk for insurers will be limited.

Part IV: Underwriting of cancer today

The current underwriting practice for cancer does not differ methodologically from the assessment of other diseases. Differences in treatment between cancer patients and applicants without a history of cancer will be applied only when these differences can be justified as is required by anti-discrimination legislation across the globe. This means there needs to be medical evidence of an extra mortality or morbidity associated with the condition, and recognised principles of actuarial calculations must have been applied to generate an underwriting decision that is commensurate with the level of risk.

To underwrite cancer, well-established clinical parameters are therefore taken into account. Decisions do not differ exclusively according to the type of cancer. Besides the location and prognosis of the cancer, other parameters are also considered for a finer differentiation. This is the case if there is sufficient evidence for the relevance of such parameters, for example:

- Age of the patient at diagnosis.

- Type of treatment carried out, e.g. surgical, chemotherapeutic, medicinal.

- Further clinical parameters individual to certain types of cancers, e.g. hormone receptor status in breast cancer, PSA value in prostate cancer.

- Current treatment status.

- Occurrence of concomitant diseases.

- Amount of time passed since diagnosis/end of treatment.

The underwriting decision will reflect the risk identified as accurately as possible, i.e.:

- The extra premium will be as high as the determined excess mortality.

- The loading is charged only for as long as significant excess mortality is expected.

- This means that some risk loadings are only applied temporarily or, should the application be made at a time when increased mortality is no longer observed, no risk loading will be applied.

- If a cancer has no (significant) excess mortality, standard rates will be applied.

This means that today a medical history of cancer – while not ignored – will not inevitably have any unfavourable impact on the underwriting decision. If no extra mortality persists, an applicant with a history of cancer will be accepted at standard rates even before 10 years since the end of treatment have passed.

Considerations on insured population mortality vs general population mortality

The cure fraction refers to the general population. Any suggestion that a mortality level or a remaining life expectancy that is equal or similar to the general population is indicative for not charging a loading on an insurance premium is inappropriate. Such comparisons ignore the differences by age and ignore the fact that “standard” insured lives have a significantly lower mortality compared to the general population due to socio-economic differences but also because the general population includes both standard and sub-standard risks.

Part V: Further considerations

The acceptance of substandard risks without a commensurate extra premium leads – at best – to higher premiums for all and – in the worst case – reduces the ability to offer voluntary insurance. To maintain an effective and affordable voluntary insurance system, the positive discrimination of some sub-standard risks should be offered in only very few circumstances that are in the general interest of society, i. e. for essential covers only and below average sums assured. For this reason:

- The insurance industry could support the RTBF only for essential Life insurance needs (mortality cover only), such as mortgage protection for, say, the first residence or own company, for the purpose of earning an income.

- The maximum sum insured should not exceed the average mortgage level in the respective country.

This will limit anti-selection and ensure access to the most important basic financial services and thereby tackle the issue of financial discrimination of cancer survivors. The experience gained in such way can be applied to any future extension of the right.

How many years after diagnosis should the RTBF apply?

We consider an uninterrupted 10 years, that is already applied in some EU countries, to be reasonable, since after 10 years of complete remission, the risk of recurrence in many cancers drops sharply or remains roughly constant from this point on.

Shortened time periods for cancers with a particularly good prognosis are reasonable, as cancer prognosis is advancing and there are more and more cancers that can be considered as “cured” even a short time after diagnosis, meaning that the extra mortality of the cancer survivors becomes negligible. Cancers with a particularly good prognosis should be defined in a medical refence grid and should be updated at least every two years.

The onset of the RTBF should be the point in time when the treating physician certifies “complete remission”, i. e. as soon as there are no longer any signs of active cancer. This can be, for example, confirmation by an imaging procedure that the cancer has been cured after completion of an appropriate chemotherapy, radiation or immunotherapy. Further control examinations to confirm continued remission in the years thereafter no longer fall under the therapy protocol, i. e. do not interrupt the period of the RTBF.

Disclosure

How does disclosure work within the RTBF? Who is supposed to “forget” a previous cancer diagnosis – the applicant or the insurer? Let us have a look at the situation in the different countries where the RTBF is already in force.

France, The Netherlands, Luxembourg and Portugal

In these markets it is up to the insurance applicant to determine whether a prior cancer diagnosis should be reported to the insurer. So, the insurance company does not get any information about a previous cancer diagnosis for which the RTBF applies.

This approach is in favour of promoting equal treatment of applicants with and without a prior cancer diagnosis. However, long-term effects of cancer treatment still need to be declared and it may be difficult for the insurance underwriter to interpret the long-term effects if a prior cancer diagnosis (and its treatment) is unknown.

It may be complicated for insurance applicants who do not have a medical background to understand the requirements of the RTBF. The applicant needs to be able to correctly define the date when the cancer was successfully treated and the respective time that needs to have passed since then, bearing in mind that some cancers can be forgotten after a shorter period of time.

- Putting the responsibility on the applicant may bear a risk of accidental non-disclosure, if the applicant interprets the RTBF in his/her favour in cases where the cancer diagnosis should have been declared, with the eventual risk of the cover being voided.

Belgium

In Belgium, disclosure works differently: the applicant makes full disclosure, and it is up to the insurer to determine whether this information should be “forgotten” or not.

- Putting the responsibility on the insurer may be the favoured approach as it prevents the risk of accidental non-disclosure; the applicant has the certainty that his/her cancer is rightfully “forgotten” in the event of a claim.

In view of the above it seems preferable from both the customer’s and the insurer’s perspective that questions on cancer should generally remain permissible. The insurers are best positioned to evaluate whether medical information is relevant and whether the information disclosed falls under the RTBF and thus must be ignored when determining the individual’s risk level. This ensures legal certainty, as:

- The periods of the RTBF differ for adolescents and adults, but the questionnaires usually do not.

- For some cancers, shorter time periods apply.

- The questions are otherwise complicated to explain the conditions including the time in remission, which can make understanding difficult.

- Questions relating to current symptoms and existing sequelae should be permissible, as they relate to the individual and current state of health of the applicant and not a blanket rating of the cancer.

If the applicant has the right not to disclose his or her cancers that meet the conditions of the RTBF, a corresponding clarification sheet must accompany the application that clearly explains the framework conditions in order to protect the policyholder and the insurer from a breach of the pre-contractual duty of disclosure.

Other chronic diseases

Chronic diseases do not fit well into the RTBF concept as they cannot be “forgotten”. Therefore, it seems preferrable not to apply the same principles to these. However, assessments for diseases that can be cured like cancer, but are nevertheless associated with a long-term increase in risk, would also have to be put to the test in the long term for reasons of equal treatment. Since the assessment practice does not differ, cancer patients would otherwise be explicitly placed in a better position than people with other diseases.

RTBF code of conduct

The industry has proved that underwriting manuals evolve over time and are aligned with medical advances and the availability of statistical evidence. It is in the industry’s own interest to insure as many lives as possible – at fair premium levels commensurate with the individual’s risk level. Existing legislation provides sufficient regulations.

The industry is advised to share more about how underwriting is conducted and that insurers have different risk appetite and that using different distribution channels allows differently sophisticated levels or depth of underwriting and thus outcomes. Instead of using legislation, an industry code of conduct may provide sufficient information to customers instead of legislation that is fraught with risk for both applicants and insurers.