-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

A Holistic Approach to Managing Depression Claims

November 08, 2021

Mary Enslin

English

Understanding depressive disorders

Depression is one of the most common mental health disorders seen in Disability claims worldwide. The principles of claims management remain the same for these types of claims. However, they have challenges specific to mental health, including distinguishing between depression versus acute or chronic stress, understanding the impact of reported symptoms, and determining the severity of the diagnosis. Mental health exists on a continuum and may change from being an acute situation to a mild or sub-clinical impairment or vice versa. Determining if or when this change occurs is a complex decision where engaging clinical experts is key.

The treatment of depression also varies by country and is not always initially done by mental health experts: General Practitioners are frequently the first point of contact with a healthcare provider. Additionally, depression is frequently used as a “catch-all” diagnosis for any kind of psychological distress and can be misdiagnosed without confirming the diagnostic criteria.1 As a result, claims for depression often lack appropriate sufficient medical evidence, which presents an additional level of complexity for claims assessors in the claims management process.

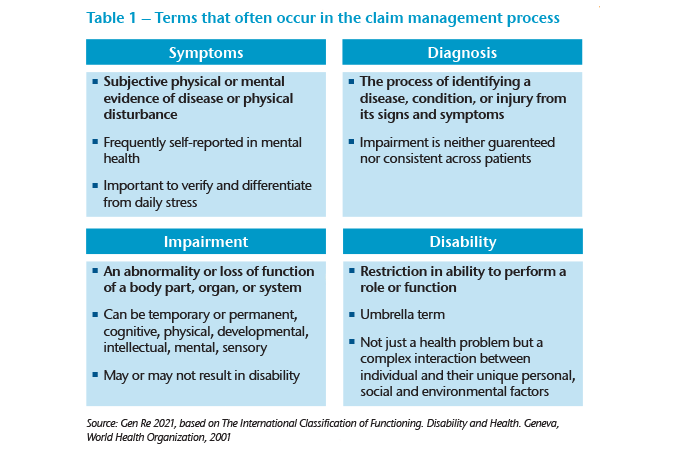

According to the World Health Organisation, diagnosis alone does not cause impairment or disability. Rather, disability results from the interaction between individuals who have a health condition and personal and environmental factors.2 It’s therefore essential to differentiate the various terms that can occur in the claim management process (Table 1).

This article explores different strategies that may be considered in the assessment and management of depression claims for Disability benefits. Each market and product is different and claims assessors need to take these differences into account. Assessment should include how the claimant’s reported psychological condition restricts or limits their ability to function in his or her occupation and daily routines within the confines of the policy terms and conditions.

Examining the diagnosis – Stress vs. depression

Depression is a common mental disorder, with an estimated 3.8% of the population affected worldwide. It affects the way people think, feel and act. It is characterized by a depressed mood (feeling sad, irritable, empty) or a loss of pleasure or interest in activities and can cause difficulty functioning in an array of emotional and physical areas ranging from poor concentration, to suicidal thoughts, to a loss of energy.3

Depression is different from usual mood fluctuations and short-lived emotional responses to challenges in everyday life. It is defined by a specific set of symptoms or diagnostic criteria and results in significant difficulty in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, and/or other important areas of functioning. Depending on the number and severity of symptoms, as well as the impact on an individual’s functioning, a depressive episode can be classified as mild, moderate or severe. Effective treatment is available for all severities of depression.4

It is therefore important to distinguish between a depressive episode and stress. Stress is a normal, human reaction that happens to everyone. It is a physical response usually triggered when one’s coping abilities are challenged by excessive pressures or other types of demands placed on them. Some stress can be a positive influence in our lives; for example, by helping to motivate certain behaviours. While chronic stress has been linked to many health risks, in and of itself it is not considered an illness or disability. An individual with mild symptoms or a tolerable stress reaction, while unpleasant, will usually not require treatment and may still be able to work in some capacity.5

Therefore, as part of the assessment of a depression claim, claims assessors should determine whether the reported symptoms and diagnosis meet the criteria of a medical illness (i.e. a clinical diagnosis of a mild, moderate, or severe depressive episode) and whether significant functional impairment is resulting from the reported symptoms and/or diagnosis.

The following considerations can assist a claims assessor in making the above distinction:

- Verify the reported symptoms against the accepted diagnostic criteria required to make a diagnosis of depression. If the treating doctor has not provided a detailed assessment and rationale for his or her diagnosis, you may need to ask for a more comprehensive report.

- Distinguish between clinical depression and sub-clinical reactions to life events or stress. For example, in clinical depression the patient often has feelings of worthlessness or self-loathing, whereas in grief, self-esteem is usually maintained.

- Understand the typical clinical course (pattern) of depression. For example, depressive moods in bereaved individuals typically do not last continuously and can be positively influenced, whereas in clinical depression neither joy nor sadness can be felt.

- Evaluate the reported impact of the claimant’s symptoms on daily functioning. It is uncommon for depression to impact only one area of life and patients typically report impairment across many domains (e.g., self-care, social activities, work, childcare/family life, etc.). If the only area impacted is the ability to work, other non-medical factors might be at play. We will explore this in more detail later in this article.

- Examine the recommended treatment. People experiencing clinical depression can rarely free themselves from their depressed mood, listlessness, and negative thoughts without external help. Any claim where time off work is the only “treatment” prescribed needs further investigation. Depression, like any other disease, requires treatment.

Optimal treatment for depression

As mentioned, having symptoms or a diagnosis of depression will not necessarily impair one’s ability to work. Therefore, consideration of all aspects of the claim, not only medical, is important. This includes a good understanding of the claimant’s functional status, the material and substantial occupational duties performed just prior to any claimed date of loss, and any financial implications. Having said that, we recognize that many claimants do not receive optimal care in line with best practice and thus a detailed assessment of the medical aspects is required.

Although known, effective treatments for mental disorders exist, more than 75% of people in low- and middle-income countries receive no treatment.6 Barriers to effective care include a lack of resources, lack of trained health-care providers and social stigma associated with mental disorders. In countries of all income levels, people who experience depression are often not correctly diagnosed, and others who do not have the disorder are too often misdiagnosed and prescribed antidepressants.7 Those with suboptimal or incorrect treatment are likely to have a longer recovery period and poorer return-to-work outcomes. Thus, while claims assessors are not directly involved in the treatment of claimants and should never give medical or therapeutic advice, it is beneficial to understand the optimal treatment available.

A combination of medication and psychotherapy is the gold standard for most cases of moderate to severe depression. A vast array of medications is available and no magic formula for choosing the “right” medication exists – the choice is a clinical one that must always be adapted to the individual person and adjusted as necessary. The effect of antidepressants is not immediate. Most people begin to see benefits after two weeks at the therapeutic dose, but it can take longer. If no change occurs after six to twelve weeks then treatment options should be reviewed with the treating specialist.8

Studies show that the average length of antidepressant treatment is less than six months and that discontinuations (non-compliances) are high, especially in primary care patients. Discontinuations are most frequent during the first month of therapy, and approximately 25% of patients do not inform their physician about stopping their antidepressant medication. Many reasons for non-compliance can exist, including side effects, attitudes towards drugs, patient‐doctor alliance, poor psychoeducation, communication failures, and the feeling that symptoms improved without needing medication, to name a few.9 If the claimant does not respond to treatment as expected, it is important to enquire about compliance with the treating specialist.

Study results provide evidence that compliance with antidepressant drug therapy is higher if psychotherapy is also provided at the same time.10 A number of different psychotherapy modalities exist but all aim to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life through discussions and exercises with a psychotherapist. The specific therapeutic goal should be clearly defined and determined beforehand. The most used methods in treatment of depression are cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and in-depth psychology-based psychotherapy.11

Regardless of the specific treatment approach taken, collaboration between the general practitioner, psychiatrist, psychologist, and other treating professionals is crucial, as are regular medical reviews. Claims assessors should stay abreast of anticipated changes in the claimant’s symptoms and/or treatment by coordinating their follow-ups to correspond with medical reviews. Standards of care guidelines may also guide claims assessors on the timing and content of their follow-ups. Both the American Psychiatric Association and the British Psychological Society and Royal College of Psychiatrists have treatment guidelines on the clinical management of depression.

In addition to timing reviews, consider what questions to ask to ensure adequate information is gathered. Detailed reports are required to gain the needed insight to determine the impact of the disorder on the claimant’s functional status. Claim forms are still the most common source of information but may have certain limitations. Targeted questions may allow for richer, more detailed information compared to generic claim forms. Many insurers are finding telephonic assessment allows for more in-depth understanding of the claim. Regardless of the chosen method of communication, the key points to consider when evaluating treatment are summarised in Box 1.

Box 1 – Points to consider when evaluating treatment

- Is the claimant being treated by an appropriate specialist (psychiatrist and/or psychologist)?

- Have specific treatment goals been defined?

- What is the treating doctor’s attitude to work? Does the treatment plan include return-to-work goals?

- What is the duration since treatment commenced? How is improvement being measured?

- Has the claimant been started on medication?

- Is the medication appropriate? Is it recommended for the treatment of depression?

- Is the dosage adequate? Does it fall within the recommended oral dosage per day?

- Has the medication or dosage been adjusted or changed recently?

- What is the response? If poor, do plans to review the medication exist?

- Has the claimant started psychotherapy?

- What type of treatment is being performed? Is the chosen psychotherapy modality (i.e. CBT) appropriate? Is it recommended for the treatment of depression?

- Is the frequency/intensity of psychotherapy adequate? Does the frequency and duration of therapy fall within the recommended guidelines for depression?

- Is a structured treatment plan in place with measurable milestones?

- If no, would the claimant benefit from psychotherapy, CBT, mindfulness, other?

- Is the claimant compliant with treatment? How has this been established?

Lastly, explore the policy terms and conditions as a means to assist the insured with return-to-work efforts. Some policy features provide rehabilitative support and may require the insured’s active participation. Claimants should be well-informed of all available treatments, ensuring that they can make informed decisions and give informed consent. However, if a claimant refuses reasonable treatment, the reasons for this should be investigated and market-appropriate procedures should be in place for managing such situations.

The role of biopsychosocial risk factors

Depression results from a complex interaction of social, psychological, and biological factors. People who have gone through adverse life events (unemployment, bereavement, traumatic events) are more likely to develop depression. Depression can, in turn, lead to more stress and dysfunction and worsen the affected person’s life situation and the depression itself. In many countries, mental illness is one of the most frequent reasons for absenteeism.12 Despite this, studies have found little association between the type and severity of mental health symptoms and/or diagnosis, the ability to work, and the duration of recovery.13 If an individual’s symptoms are not the primary reason they stop working, it is important for us to consider what other risk factors might be influencing the claim.

Risk factors are those characteristics, variables, or hazards that, if present for a given individual, make it more likely that this individual, rather than someone selected at random from the general population, will develop a disability. Risk factors can also have an unfavorable impact on the prognosis, i.e., the duration of therapeutic measures, the severity of the disease, or the probability of recurrence. Secondary gain factors (e.g., a financial benefit resulting from disability such as receiving an insurance benefit) may also have an impact.14 These considerations mean it is important to identify all risk factors at play and develop a comprehensive claim management plan to address them.

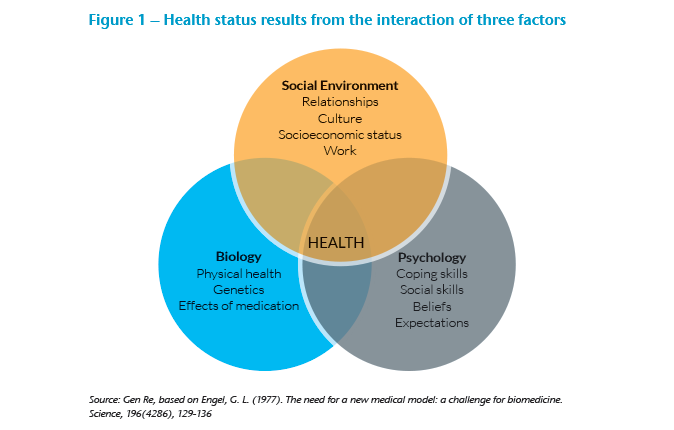

A common model for understanding the role of risk factors on mental health is the biopsychosocial (BPS) model, which Gen Re has explored in previous articles. In short, this model presents a holistic means of understanding the precipitating and perpetuating factors that may contribute to an individual’s health. The model proposes that a person’s health and well-being are not determined solely by biological characteristics. Rather, as shown in Figure 1, health status results from the interaction between biological (physical health, genetics, medication effects), psychological (coping skills, social skills, beliefs and expectations, mental health) and socio-environmental factors (relationships, culture, socioeconomic status, work).15

The BPS model can be a useful tool for claims professionals wishing to deepen their understanding of the various medical and non-medical factors contributing to a workplace absence. Claims assessors may wish to evaluate their claims forms and other methods of evidence-gathering to determine if these are sufficient for understanding all domains of the claim. For example, an individual may receive excellent medical care and engage well with prescribed treatment, but if serious, unresolved conflict exists in the workplace, it may present a significant barrier to recovery and return to work. You can read more about the role of biopsychosocial factors in claims management in the article The Role of Resilience and Self-Efficacy in Mental Health Claims Management.

Since depression is usually accompanied by a feeling of overtaxing and exhaustion, work is often mistaken for the cause of depression. In fact, conversely, work is usually a protective factor, as the regular daily structure, productivity, social interaction, and acknowledgement required for most jobs provide support. Many clinical and rehabilitation best practice guides now acknowledge the protective and positive effects of work and recommend keeping those experiencing a depressive episode in work at almost all costs. Only those with severely debilitating symptoms should be prescribed time off work for any lengthy period.16

Having established a detailed understanding of the occupational and workplace dynamics, claims assessors have several tools at their disposal to address any barriers preventing a return to work. These will vary from market to market and are influenced by local labor legislation and the specific details of each claim. Work-directed treatment, combined with medication and psychotherapy, has been found to be successful in many common mental health diagnoses, especially depression. Early intervention is key. The longer an individual is absent from work, the lower their chances are of returning to work. It follows that a supported return to work following a medical absence should be initiated as soon as possible.17 Claims assessors should consider whether any of the following are appropriate:

- Develop a personalised claims management plan that identifies key barriers, strengths, and milestones. Included in this should be clear expectations regarding frequency of communication, expected recovery (if known) and anticipated milestones in the claims process (e.g. evidence due dates, payment dates if valid, review dates, etc.).

- Proactively manage the claim and monitor progress with regular reviews at appropriately timed intervals, adjusting the management plan as needed. For example, if treatment was only recently started or an adjustment has been made, it may be appropriate to allow some time for treatment to take effect before scheduling the next case review. On the other hand, doubtful cases may need to be reviewed more frequently.

- If appropriate, educate both claimants and treating doctors on the benefits of "good work" by sharing research or brochures. Some initiatives encourage doctors to “prescribe work” as part of treatment.

- Consider an Independent Medical Examination (IME) or a Functional Capacity Evaluation (or similar assessment) by a suitably qualified specialist.

- Understand what reasonable accommodations exist and are supported by legislation in your market. These may include: a graded return to work, a flexible work schedule, adjusted duties (temporarily or permanently), appointing a mentor, allowing work from home, introducing more frequent rest breaks, making available a rest area or private space, identifying and reducing triggers, and many more.

- Use regular positive communication and behavioural economics to develop self-efficacy, resilience, and positive coping strategies. For more information on communication, the use of behavioural economics, or any of the above topics please contact the author.

Conclusion

While the average duration of a depressive episode is four to eight months, the average absence from work is even shorter at two to three months.18 Therefore, the prognosis for most cases should be promising, as long as adequate treatment is provided and any biopsychosocial risk factors are addressed. Claims assessors should manage the claim proactively using the recommendations above to avoid any delays.

It is critical to differentiate between acute stress and clinical depression. To assess the degree of functional impairment against the policy terms and conditions, it is necessary to make a detailed exploration of all symptoms, the response to treatment, the impact of biopsychosocial factors, and the overall effects on the claimant’s ability to work. By understanding the typical presentation of depression, keeping abreast with the current recommended treatments, developing clear claim management plans, and knowing what resources are available to address any biopsychosocial risk factors, claims assessors will be equipped to manage these complex claims.