-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Long Term Care Reform in Germany – At Long Last

July 30, 2019

Sabrina Link

Region: Germany

English

In many countries, how to fund support for old age is a growing issue. At the start of 2017, the German compulsory Long Term Care (LTC) insurance scheme underwent comprehensive reform that reframed the definition of care. Besides introducing a new “in need of care” definition, the reform also added a new evaluation instrument for determining the need for care.

This paper gives background information on the German LTC social security system, presents the new definition and the new care assessment and points out the major changes. It focuses on lessons learned and first experience under the new system, which might be interesting and helpful for other countries. It concludes with the implications this reform has for the private insurance industry with respect to in-force policies, designing of new products and pricing.

Background

LTC insurance, be it public or private, is designed to protect against costs that arise from care needs. It provides cover against the risk of becoming too frail to care for oneself without physical assistance from another person even when using assistive devices.

Demographic and societal changes continue to put pressure on society with respect to elder care. In particular, increasing life expectancy and decreasing fertility rates mean that more people reach a care-relevant age with fewer people to support them. In 1980 life expectancy at age 65 was only 12.8 years for men and 16.3 years for women in Germany (12.6 for men and 16.6 for women in the United Kingdom). In 2015 it was already 17.9 years for men and 21.0 years for women (18.6 for men and 20.8 for women in the United Kingdom) – reflecting an increase of four to six years of life expectancy over a 35-year period.1 In most developed countries, the fertility rate has been below the replacement rate of 2.1 for decades now. It was only 1.5 in Germany (1.8 in the United Kingdom) in 2015 and has been this low since the early 1970s.2 An increased mobility of the younger generations, a higher labour participation by women, and the fact that families are getting smaller and less stable, imply that close relatives who have been the traditional choice in the past are now less likely to take on the role of caregivers.

In countries where a public system exists that encompasses elderly care, these demographic and societal changes exert pressure on the social system since they translate into a smaller share of the population that is of working age. A measure that puts a number on this phenomenon is the old-age dependency ratio. It sets the number of persons aged 65 and over (the age when they are generally economically inactive) in relation to the number of persons aged between 15 and 64 (working age). In the EU-28 countries, this ratio is projected to increase from 0.288 in 2015 to 0.503 in 2050, which indicates that only two persons of working age will be there to support one pensioner.3

The majority of people will need care support during a certain period before death. The experience from a German public health insurer reveals that more than half of all men and almost three out of four women require care at the end of their lives, and that more than 80% of them require it for more than three months.4 Finding solutions to fund the care of the elderly is therefore of key importance in ageing societies.

Germany

Germany is one of the few countries with an established public LTC system and where government and private solutions coexist. In 1995 the public LTC insurance scheme was introduced as the last of the five pillars of social insurance in Germany. Coverage is compulsory, and people are usually insured through their health insurer. The financing of the scheme is based on a pay-as-you-go system. The contribution rate has increased from 1% of gross income at the outset to the current 3.05%, and is shared equally between employee and employer. Those without children pay a surcharge of 0.25 percentage points. The principles of the system are, firstly, the partial nature of the scheme, which bears around half of the actual cost incurred by an individual in need of care. Secondly, home healthcare should take precedence over nursing home care. The benefits are not means-tested and do vary, depending on whether a cash benefit or the reimbursement of care costs is chosen and whether care is provided at home or in a nursing home.

When the compulsory LTC insurance scheme was introduced, it had three care levels. The assessment of the level of care took account of the frequency and duration of the assistance required to provide for personal hygiene, feeding, mobility and housekeeping needs. Other activities, such as measures to promote communication and general care, were explicitly not taken into account. In reaction to the criticism of the focus on physical abilities, a “level 0” was added later. Small levels of benefit were granted to individuals with limited daily living skills, including mainly those with cognitive impairments, such as dementia, but no physical care needs. In addition, the highest care level differentiated so-called hardship cases that manifested extremely high and intensive care needs and surpassed the usual extent in care level III.

The three care levels and hardship cases were defined by the following criteria:

- Persons in care level I require assistance for the basic activities (personal hygiene, feeding and mobility) at least once a day and several times a week for housekeeping.

- Persons in care level II require assistance for basic activities at least three times a day and several times a week for housekeeping.

- Persons in care level III require assistance daily and around the clock for basic activities and several times a week for housekeeping.

The length of time a non-professional spends on average per day caring for the dependent person has to amount to:

- At least 90 minutes, more than 45 minutes of which are for the basic activities in care level I

- At least three hours, at least two hours of which are for the basic activities in care level II

- At least five hours, at least four hours of which are for the basic activities in care level III

Persons in care level III counted as hardship cases if they either needed assistance for the basic activities for at least six hours daily, including at least three times at night, or if the assistance for the basic activities could only be rendered by several care persons together, including at night. Hardship cases were present especially for terminal cancer, terminal AIDS, high paraplegia and tetraplegia, vigil coma and severe manifestation of dementia amongst others.

The reform

From the outset, two features of the care assessment and definition were especially criticized: the insufficient consideration of cognitive aspects and the unsuitable counting of minutes as a criterion to assess the need for care. Over the years, various legal extensions were therefore instituted but never included a thorough reform of the system. Benefits were expanded, “level 0” was introduced (first only for those with a care level, later for all) and a provident fund was established.

Since 2013, a government initiative has promoted private insurance by subsidising (small) premiums, the so-called “Pflege-Bahr”. Nevertheless, a reform was concretely envisaged already in 2006 when an advisory committee to review the care definition was initialised. This committee accomplished much important groundwork, such as outlining a new definition and assessment after thorough research and pre-testing the proposed assessment instrument. Due to changing governments after elections and shifted priorities, further work was delayed, but not abolished. A second committee revised and concretised the new care definition and two larger studies were conducted to validate the new assessment process. Finally, in 2015 the Second Pflegestärkungsgesetz (PSG II) (i.e. the Second Strengthening-of-Care Act) was passed and took effect at the beginning of 2017, more than 10 years after its initialisation. It is embedded within the framework of the First Pflegestärkungsgesetz, which brought an expansion of benefits and the setup of the LTC fund in early 2015, and the Third Pflegestärkungsgesetz, which is to strengthen care counselling in the municipalities from 2017 onward. With the contribution rate increased by 0.2 percentage points, the financing of PSG II was deemed sufficient at the time. However, another increase by 0.5 percentage points from 2019 onward had to be realised.

The new care assessment and definition

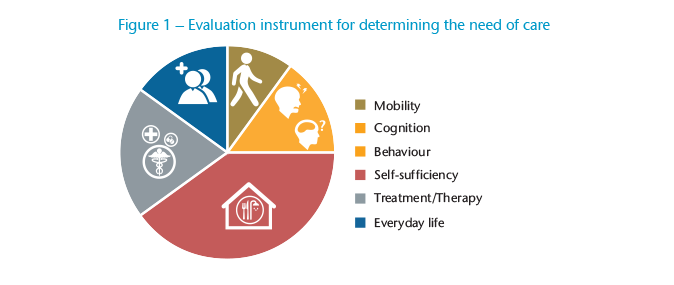

The new evaluation instrument for determining the need for care comprises six modules that are weighted differently in the final overall score (Figure 1):

- Mobility (10%)

- Cognitive and communicative abilities (higher value from module 2 and 3, in total 15%)

- Behaviour and psychiatric problems (higher value from module 2 and 3, in total 15%)

- Self-care (40%)

- Dealing with requirements due to illness or therapy (20%)

- Organisation of everyday life and social contacts (15%)

Each module consists of various items. For each item, the assessor records how independently the applicant can perform an activity, if or to what extent an ability is present or how often a certain behaviour occurs. The applicant receives one of the five care grades if the total score is above 12 points of a total of 100 points. For the highest care grade, a special rule applies, and is granted if the applicant has a score of at least 90 points or has lost the use of both arms and both legs.

The assessment philosophy is characterised by five fundamental changes:

- The allotment of time required for care was replaced by the degree of independence. Heretofore, the evaluation was based on how often and how long the dependent person needed assistance. To that end, the assessor drew on benchmarks as reference points, a complete takeover of the activities by a lay caregiver being assumed. For example, a full-body wash was graded with 20 to 25 minutes. From now on, the extent to which the applicant can shower or bathe independently will be captured.

- The former deficit orientation is replaced by a resource orientation. It is therefore not a question of what the person in need of care can no longer do, but rather what he or she is still able to do.

- Previously, the need for care in some activities of daily living was taken into account, consisting of personal hygiene, nutrition, mobility and household assistance. In the future, there will be a comprehensive consideration of the care need. Cognitive and psychiatric impairments will be considered especially in modules 2 and 3 and to some extent in modules 5 and 6. In modules 1 and 4, on the other hand, special emphasis is placed on physical impairments, which continue to be of great relevance due to the high weight of these modules in the total score.

- The earlier three care levels have been replaced by five care grades. The lowest care grade only serves as a type of preliminary level, though. It has an easy-to-achieve minimum score and relatively low cost reimbursement benefits that can only be used for their specified purpose.

- In the past, a person had to actually be dependent on assistance for the respective activity. In the future, it will be irrelevant whether the activity in question actually occurs. For example, independence when climbing stairs will be assessed even if there are no stairs in the applicant’s individual living environment.

It is noteworthy that with regard to inpatient care, the contribution to be paid by the person will no longer be dependent on the care grade (except for the lowest care grade). A transition to a higher care grade will therefore not lead to higher contributions, which often led to conflicting interests between nursing home operators and the person in need of care or their relatives. It should be noted, however, that the exact amounts of the deductible and additional costs for investments, board and lodging differ from nursing home to nursing home.

For those who already received benefits from the public LTC insurance system before the reform in 2017, the protection of the status quo is politically intended. Those people are automatically transferred into the new care grades and continue receiving at least the former benefits. A former categorisation into care level x is transferred to care grade x+1. If the dependent person also has limited daily living skills, he or she is transferred to care grade x+2. For example, an individual with care level II before 2017 will be re-categorised into care grade 3. If limited daily living skills were observed in addition to care level II, the person will be categorised into care grade 4.

Implications for private insurance

Additional private LTC insurance policies are available from both the Health and Life insurance line – sometimes with considerable differences. Health insurers offer daily allowances, subsidised LTC insurance policies and the increasingly less important cost reimbursement policies, while life insurers offer annuities. Due to the possibilities to adjust premiums in daily care allowances, the higher guarantee level (including a surrender value) in care annuities and varying interest rates, the price-performance ratios of the policies cannot be compared directly. The initial premium for daily care allowances may appear less expensive when looked at in isolation. This may be one of the most important reasons why the number of in-force policies for health insurers is much higher, amounting to 3.7 million at the end of 2017.5 Even though life insurers managed a portfolio of only 220,000 policies, at the same time they enjoyed a strong growth in recent years.6 Between 2005 and 2017 the number of policies has increased by 24% on average per year, compared to an average annual increase of 13% for Health insurance products.

For LTC insurance policies offered by health insurers, Germany’s PSG II provides for a special adjustment right for conditions and premiums, and even provides a duty to adjust the tariffs in compulsory private LTC insurance and nationally subsidised additional LTC insurance policies. Additional private policies follow the procedure in the compulsory private LTC insurance. For one, this means that the new definition of “in need of care” will be used in new business. It also means benefits offered under existing policies have been adapted based on the new definition of “in need of care”.

Products available from the Life insurance line previously used three definitions – the legal definition of “in need of care”, a definition based on activities of daily living (ADL), and an independent definition of dementia – as benefit triggers. The legal definition was typically copied into the contract wording at a certain point in time with a commentary that changes in the public definition would not lead automatically to changes of the tariff, implying that claims management retained the right to do their own assessment. Because the need for financial support typically increases with the level of dependency, tiered benefits were very popular. This means that the benefit amount depends on the care level or the number of failed ADLs. For example, the insured person receives a partial benefit when failing four out of six ADLs, fulfilling the requirements for care level II or when suffering from dementia and the full benefit in the highest category.

In future claims assessments involving pre-existing policies, two situations are possible: Either those three benefit triggers will have to be taken into consideration, which does not seem impossible since the assessment report based on the new evaluation guidelines will be available; or the insured person will have opted to switch to a new policy, an option that most recent tariffs offer. No new underwriting is required, but the change of tariff must not lead to an extension of the cover, which can lead to a changed (usually lower) benefit than before, due to the more generous nature of the new care definition. Switching to a new tariff can have advantages for the policyholder, even though some specifics, such as the gender-differentiated calculation and higher guaranteed interest rates in earlier product generations, have to be dealt with adequately.

Due to the legal definition, one must ask how a new policy should look. Sticking to the old care levels would do no favour to either the carrier’s public image or its claims management. On the other hand, life insurers have been engaged predominantly with other issues, such as regulatory requirements or the reorientation of private pension products, with the result that only a little capacity is available for revising the LTC product. Thus, there are currently providers that, for the time being, are continuing to use the old care levels or are not using the legal definition at all, favouring the definitions of ADLs and dementia instead.

It is worth considering whether to use the new legal definition exclusively, which covers both physical and psychological disabilities. A separate definition of dementia would then no longer be necessary. On the other hand, a parallel definition of ADLs could at least provide a fallback option in case of future reforms of the public LTC system, even though this might seem unlikely at the moment with the flaws of the old definition appearing to have been corrected. Aside from that, such a parallelism would follow the former market standard. Both variants are currently to be found on the market; some carriers have opted to use only the new social security definition going forward, while others combine it with an ADL definition complemented by a cognitive element to imitate the legal definition.

Tiered benefits still make sense for home healthcare, since the need for financial support continues to be different for each care grade. For nursing home care, this is no longer the case due to the above-mentioned new regulation that the contribution to be paid is no longer dependent on the care grade. However, no one will be able to tell whether potential care will be delivered at home or in a nursing home when taking out LTC insurance. Most products on the market offer an individual fixing of the benefit amount per care grade.

As mentioned above, the lowest care grade (care grade 1) serves as a type of preliminary level with an easy-to-achieve minimum score and relatively low mandatory benefits. The calculation of this care grade involves a number of uncertainties as the assumption regarding the number of additional benefit recipients to expect has a major impact. It therefore seems wise to offer no cover – or only very low cover for care grade 1; for example, in the form of a lump sum benefit. Even a waiver of premiums for reaching care grade 1 could jeopardize the profitability of the tariff because the insurer might not gain enough premiums to pay out later benefits. Therefore, for most products on the market, care annuities can only be paid, and premiums only waived, from care grade 2 upwards.

Differentiating between care grades 4 and 5 is fraught with higher uncertainties than when looking at the other care grades. For the most part, cases with the former care level III can be expected in both care grades. Since further progressed cases with care level III were underrepresented in the studies prior to the reform, differentiating between these two care grades in the calculation is very risky. Furthermore, the average time needed to provide care is nearly the same in care grades 4 and 5. Thus, it is recommended to allow for the same or at least very similar benefit amounts in these care grades. Some products on the market combine the highest two care grades at the outset. Products with fixed levels of benefits offer a high percentage of benefits in care grade 4.

One must also consider whether the assessment of risks in medical underwriting has to change. Dementia-related or mental illnesses affecting behaviour and conditions that involve the patient in the monitoring and/or treatment processes are weighted more heavily than in the past. Fundamental changes in the previous assessments are unnecessary. For example, due to the predictability of care dependency, it was normally impossible to obtain insurance for psychotic schizophrenia, especially when dementia represented an independent benefit trigger.

Another major question is how pricing rates can be derived for the new definition when there has been no actual experience at all. The former relatively robust rates for care levels can be transferred to the new definition using, for one thing, contingency tables of care levels and care grades. These can be obtained from the studies prior to the reform, during which applicants were assessed simultaneously with regard to the former and the new assessment system. Various adjustments might be necessary, like taking into account the effect of “lifting-over-the-threshold”: When assessing claimants with real benefits resulting from it, a gap in the distribution of the scores at the threshold to the next higher care level can be observed. This means that almost no claimant receives a result close to the next higher care level, but clusters receive a score just over it. Scores close to the next higher care level would only lead to objections and, due to the worsening state of health of almost all care recipients, a reassessment only a short time later would confirm the justification of the higher care level. In a study setting, however, this gap cannot be observed, but will probably occur for care grades as well.

Additionally, assumptions about the number of additional benefit recipients are necessary. These are the people that were not care-dependent with regard to the old system, but will be granted a care grade in the new system. One approach is to estimate the number of those who applied but were rejected in the care level system and those who never claimed but are likely to do so in the care grade system. Since the new system has been in place for over two years, first numbers have been published. Public sickness funds, which account for approximately 94% of care recipients, have stated that by the end of 2017 around 304,000 people will have been granted a care grade, but would not have received benefits in the old system.7

Conclusion

The objective of providing more appropriate care grading through the LTC reform appears to have been achieved. In future, people with cognitive and mental health problems will be shown the same recognition for their limitations as people with purely physical impediments. Resource orientation and a focus on the degree of independence replace deficit orientation and the focus on the length of time required for care.

The design of the new care definition and assessment may serve as an inspiration for public LTC schemes elsewhere, be it for schemes to be newly introduced or existing ones to be adjusted. Linking the benefit trigger of a private LTC product to the public definition entails a lot of questions that have to be solved in advance in case of a reform. The challenges for the private insurance industry pointed out above may help private insurers in other countries weigh whether to use the local definition in their products or to use an independent benefit trigger like one based on ADLs. The first has the advantage of a high recognition value for the potential policyholders, but the example of Germany shows that dealing with a reform is a complex and effortful task.

Even though many questions had to be clarified for the practical implementation, some German providers of private LTC insurance have already integrated the new definition of “in need of care” into their products. It remains to be seen how the private insurance market will develop in light of the reform. Insurers will have to maintain a balance between comprehensive insurance cover and payable premiums, as private LTC insurance will remain one of the fastest-growing and future-proof products on the German insurance market, not least due to the demographic trend.