-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Florida Property Tort Reforms – Evolving Conditions

Publication

Is Human Trafficking the Next Big Liability Exposure for Insurers?

Publication

When Likes Turn to Lawsuits – Social Media Addiction and the Insurance Fallout

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance

Publication

Engineered Stone – A Real Emergence of Silicosis

Publication

Who’s Really Behind That Lawsuit? – Claims Handling Challenges From Third-Party Litigation Funding -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Understanding Physician Contracts When Underwriting Disability Insurance

Publication

Voice Analytics – Insurance Industry Applications [Webinar]

Publication

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists – From Evolution to Revolution U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

Always On: Understanding New Age Addictions and Their Implications for Disability Insurance

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

How Insurers Can Prepare for the Impact of Digitisation on Employment

July 03, 2018

Roman Hannig

English

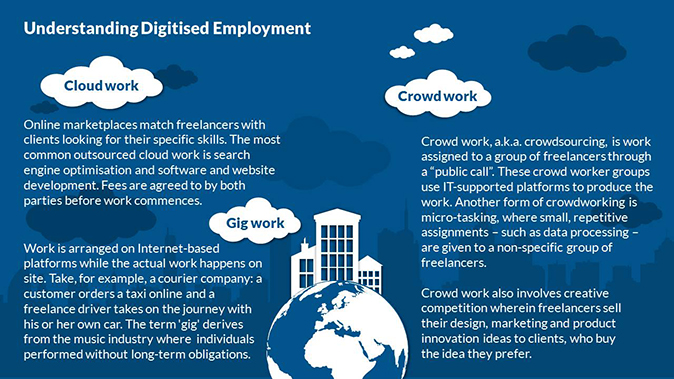

The way we all work is being shaped by digitisation. The employment lexicon, for example, includes new terms - gig, cloud and crowd working. The effect of digitisation on traditional jobs and workers prompted the German Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs to publish a white paper, entitled “Work 4.0”. Here in Germany, policymakers present a future of quality jobs in a digital era - a vision for employment that builds on the German social and economic model.

Many people see flexible and self-directed working as positive changes, despite the higher demands for the personal organisation and efficiency it demands. One drawback of the new models described here is that social protection is reduced;1 employment status may also be less clear and remuneration mechanisms are more precarious.2

Digitisation is making work tasks flexible in terms of time and place. Cloud work and crowdsourcing offer much more elastic working hours, at least partially. For a number of years in Germany, for instance, workers’ demands for less rigid work patterns have been met with flexitime, trust-based working hours and telecommuting. The question remains if this free time is actually, well, free.

Being available for work during “free time”, coupled with atypical hours, threatens work-life balance. Working from home may muddle the distinction between business hours and leisure time, placing stress on individuals’ physical health and mental wellbeing.

Working overtime routinely is also known to impact health: one survey found 50% of workers had occasional back pain and muscle tension regardless of whether they worked 30, 40 or over 50 hours per week.3 In contrast, exhaustion and burnout became more frequent as the number of working hours increased.

People who consistently work too long are at a known risk of high blood pressure, cardiac arrhythmia and heart attack. Their risk of suffering gastrointestinal disease also increases.4

In data from the German Federal Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs, 17% of workers - 29% at management level - complained of increasingly blurred lines between their professional and private lives.5 In the same survey, just 14% of respondents who reported working in relatively poor conditions considered their health to be very good.

As new models for work often go hand-in-hand with less social protection and sometimes with relatively poor remuneration, pressures on these workers could increase, leading to increased incidence of physical illness in future.

Disability income insurers should closely watch these developments in regard to Disability insurance. As old established work tasks evolve and new ones emerge, the following factors might also have an influence on the assessment of claims.

New roles and work patterns are shaping the world of work with increasing significance, while the line between work and free time is blurring.

Claimants may be inclined to report longer and longer working hours, which would have a negative effect on the results of an assessment where 50% impairment means receiving the sum insured.

Trust-based working hour models could increase the discrepancy between actual and contractually agreed working hours. In crowdsourcing, long working hours can mean poor remuneration. The difference between employed work and self-employment is becoming distorted.

In some cases, new ways of working cause greater stress. The new “freedom” does not mean that a person has to work less in order to earn a living - quite the opposite: overwork, worries for the future and physical problems could be the result. Insurers should be aware that the risk of people trying to take recourse in occupational disability due to a lack of economic success might increase.

Endnotes

- Hans Böckler Foundation, Böckler Schule: “Crowdworker - selbstbestimmt oder ausgebeutet?” and Christine Gerber, Martin Krzywdzinski: “Schöne neue Arbeitswelt? Durch Crowdworking werden Aufgaben global verteilt”, WBZ Mitteilungen, Heft 155, 03/2017.

- Wolfram Brehmer, Hartmut Seifert: “Sind atypische Beschäftigungsverhältnisse prekär? Eine empirische Analyse sozialer Risiken”, source: http://doku.iab.de/zaf/2008/2008_4_zaf_Brehmer_Seifert.pdf.

- Statista survey 12-18 2017; 1,039 respondents aged 18 and over, German-speaking resident population.

- “Flexible Arbeitszeitmodelle für eine neue Zeit der Arbeit”, Dr. Guido Birkner, Health Manager, Edition 4, 11/2017.

- “Was sich Arbeitnehmer wünschen”. Study by the German Federal Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs, 2015.