-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Biometric Information Privacy – Statutes, Claims and Litigation [Update]

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves?

Publication

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Illinois Changes Stance on Construction Defect Claims – The Trend Continues

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Four Aspects of the Current Debate

Publication

Battered Umbrella – A Market in Urgent Need of Fixing -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Underwriting High Net Worth Foreign Nationals – Considerations for U.S. Life Insurance Companies

Publication

Group Term Life Rate & Risk Management – Results of 2023 U.S. Survey

Publication

Trend Spotting on the Accelerated Underwriting Journey

Publication

All in a Day’s Work – The Impact of Non-Medical Factors in Disability Claims U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

Marginal Gains in the Medicare Supplement Market -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

How Using Behavioral Economics Can Improve Underwriting Results

January 12, 2017

Region: North America

English

It seems one cannot attend a conference or pick up a trade magazine these days without finding some mention of behavioral economics (BE). From policy development and healthcare to retail and now, insurance, many industries are finding interest in this area of study. What is yet to be fully appreciated, though, is just how significantly BE can improve business outcomes for insurers.

At Gen Re we have been studying how the principles of BE can be applied in life and health insurance, and we are excited by the possibilities. What is particularly appealing is the potential to influence positively the interactions insurers have with their customers. Effective use of BE concepts in the design of application form questions, for example, promises to help people make more accurate disclosures, which in turn means underwriters can make better and fairer decisions.

Our experiments, which are aimed at learning how to nudge (or influence) consumer behavior during the insurance purchasing process, have demonstrated the power of BE. We conclude that incorporating these ideas and concepts promises to deliver more effective risk management, improved sales and better customer retention.

Application form questions and BE

Behavioral economics is where psychology and economics intersect. It is a science that seeks to understand how and why individuals make decisions. Behavioral scientists believe that cognitive limitations affect most people’s ability to use and understand the information available to them. Through research by noted psychologists such as Daniel Kahneman, we know people have two systems of thinking: fast thinking, based on intuition and automatic processing; and slow thinking, which is deliberate and requires more work.

Forming a perception of a stranger encountered in the street, simply based on how the individual walks or what the person wears is an example of fast thinking. Even in situations more conducive to slow thinking, people favour fast thinking because the intuitive processing system is automatic and cannot be shut down. A better understanding of how people process information, and the mental shortcuts they use, can help us explore ways to nudge them to certain behaviors.

An example of how BE can be useful comes from our research into disclosure during the application process. The work was prompted by the thinking of Dan Ariely, a leading proponent of BE.1 One of Ariely’s main principles is that most people will “only be dishonest to the point they can still feel good about themselves.” How to help people disclose relevant risk data to an insurer is an issue that led us to review some of the questions on current application forms in the U.S. market and to consider how these might be improved.

If you are reading this and already thinking, “There is no way we can change our applications,” then it won’t matter how well we prove that there are issues with them, as you have thrown in the proverbial towel. However, the following discussion may change your mind and motivate you to review your questions. In fact, the hope is you will even consider sitting down with a customer and ask how they interpret the meaning of the questions, and then see if our findings hold true. The remainder of this article considers four main areas of difficulty that were uncovered and shares some examples from the applications that were reviewed.

Tobacco and drug questions

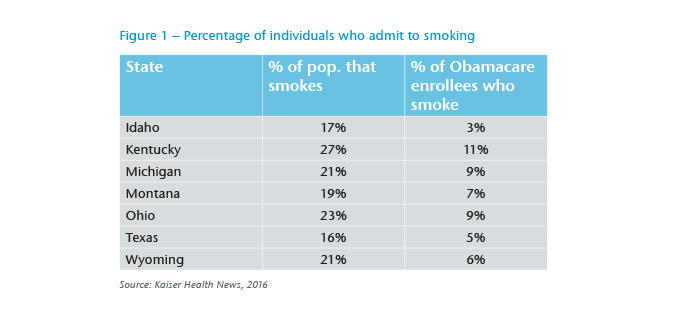

First, we will focus on the tobacco usage questions found on many applications. Underreported smoking has a direct impact on premiums and claims paid. An interesting trend arises by comparing the percentage of Americans who enrolled in health insurance schemes under the Affordable Care Act (colloquially known as Obamacare) and who disclosed smoking, versus the percentage of state residents who claimed to be smokers (see Figure 1). Although the figure is only showing the comparisons for a few states, the findings are consistent. In the majority of the states where tobacco use was tracked, the percentage for those who were enrolled and who disclosed smoking was significantly below that of the states’ average.

One explanation for the difference is the premium incentive (non-smokers are charged a lower rate than smokers), which may well be known to applicants. However, there is also an element of social stigma that comes with admitting being a smoker and addicted to nicotine. We can dig deeper into this aspect by considering a tobacco question taken from a current application form (see Example question 1 in the blue box below).

Note that a “Yes” answer to this broad question, “Have you used tobacco or nicotine delivery products in any form in the past 12 months? Yes or No?”, is an admission that the respondent is a tobacco user. This might seem subtle but it is very powerful in terms the social stigma attached to the label “tobacco user” and the need to feel good about oneself.

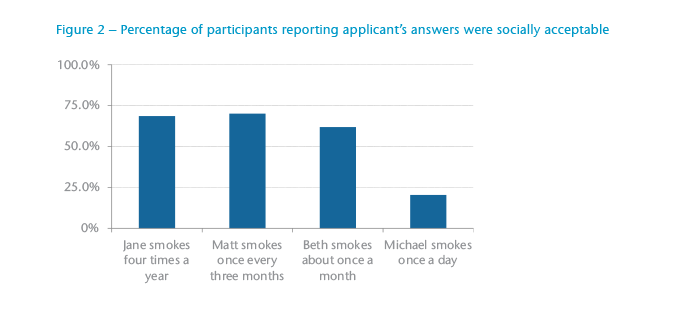

For further evidence of the power of social acceptability, we conducted an online survey of individuals (age 18 or older) that included the following scenario: Four people were applying for individual life insurance. As part of their life insurance applications, each was asked if he or she has smoked in the past 12 months.

The results reveal that the participants were generally content with classifying a person as a social smoker if the person answered “No” to using tobacco in the past 12 months (see Figure 2). Much of the participants’ response was due to how a tobacco user is perceived. For example, which of these is a “tobacco user”: someone who smokes on a regular basis – most likely once or more a day – someone who needs the nicotine, or someone who smokes only when around friends?

Another problem area for insurance applications involves questions about drug use. Many of the applications we reviewed included Example question 2.

The primary drawback of this question is that it combines enquiry on multiple substances, including a number that are illegal. While marijuana may not be as much of an issue in some markets, the other drugs listed likely are, and the question is so broad that it isn’t clear specifically as to what drugs have been used. While many applicants can honestly answer they have never used any of the drugs listed, some who have only tried or used marijuana in the past may hesitate to disclose it in the context of this question. Thus, the wording of the question could garner a less-than-truthful response because people do not want to admit socially unacceptable behavior.

Example question 1

Have you used tobacco or nicotine delivery products in any form in the past 12 months?

Yes or No?

Example question 2

Are you currently using or have you EVER used ecstasy, marijuana, cocaine, amphetamines, hallucinogens, heroin, or any other drug except those prescribed by a medical professional?

Yes or No?

Example question 3

Have you had or ever been diagnosed, treated, or received medical advice by a member of the medical profession for any of the following (listed medical conditions)?

Yes or No?

Example question 4

Have you ever consulted a physician or received treatment or advice or been hospitalized because of your alcohol use? If YES, provide dates, hospitals, treatment centers and physicians’ names and addresses.

Example question 5

To qualify for preferred rates you must be able to answer “No” to the following question; have you used tobacco in the past 12 months?

Example question 6

To qualify for this insurance you must be able to answer “No” to questions 2-10.

Multi-part questions

Another issue we uncovered in our research concerns some of the approaches to asking medical questions. Many of the applications we reviewed ask multiple medical questions within the context of one question (see Example question 3).

This example actually asks three different questions an applicant must consider when reviewing the list of conditions: “Have I been diagnosed?” “Have I been treated?” “Have I received medical advice?” Handling this type of question requires work. It is challenging for the applicant to think through answers to each subquestion. We know individuals do not want to work that hard and are programmed to use “fast thinking”. Consequently they are also likely to generate a fast response that may not be the most accurate.

Complex, multi-part questions like these often occur in the middle of an application form process. An applicant must answer them after having spent considerable time responding to questions about the products and levels of coverage they need, and even how they want to pay premiums. No wonder an applicant might slip into fast thinking to get through the question.

Incentive questions

We also found that some current application form questions actually provide individuals with incentives to misrepresent their situation (see Example question 4).

This might not seem obvious, but if there is one thing that BE teaches us, it’s that people don’t want to do more work than is necessary. Consequently, the idea of answering “No” to avoid answering the second question is appealing enough to be considered an incentive. While insurers need to obtain the additional information, our recommendation is to avoid asking for it until later in the form.

Finally, consider two further examples (see Example questions 5 and 6).

Would it be surprising if many people answered “No” in example 5? Instead of encouraging honest answers to these questions, insurers are motivating the applicants to offer answers that will give the applicants the best advantage.

In closing

While the goal of our research was to test how BE can be utilized to improve disclosure rates, we began by identifying potential problem areas. The above are just a few examples of how current applications encourage fast thinking, resulting in people providing less accurate information in applications for insurance. Our research has shown, however, that using a BE approach to constructing application questions can improve the quality of the questions asked, as well as the risk information received.

Endnote

- Ariely, D., The (honest) truth about dishonesty: how we lie to everyone – especially ourselves. HarperCollins, New York, (2012).