-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Critical Illness Standardisation – The Asian Perspective

September 21, 2016

Pei Nee Yong,

and Dr. Wolfgang Droste

Region: Asia

English

Three decades have passed since the original Critical Illness (CI) insurance products were launched in South Africa – covering only four medical conditions, and defining them seemed straightforward. Now CI coverage typically extends to more than 50 defined conditions and products have complex proportional tiered benefits.

Diagnostic shifts and developments in medical treatment impact the definitions in CI products. This would not be problematic were CI sold as an annual or short-term health product with reviewable terms and conditions. Instead, it is mostly sold as life insurance and regulators therefore demand that the conditions, if not even the premiums, are guaranteed for the full term of any policy.

Asia is by far the most dominant CI insurance market, with sales from China alone exceeding 10 million policies per annum. Insurers all face the dual challenge of finding definitions that will not result in a drastically different number of admissible claims as diagnosis and treatment options change – and that price the product in a sustainable way. Standardised CI definitions, already used in many markets, might help the various Asian markets to address these issues.

The Asian perspective

In the UK definition standardisation was driven by the desire of intermediaries for more comparable products and reduced confusion amongst consumers and salespersons. In Asia the perspective has been different. This is because Asian markets are dominated by two sales channels, tied agents and bancassurance, with the latter hardly selling any protection.

Regulations in Asia are undergoing change, but when CI was introduced, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China operated as traditional “tariff markets” with strict pricing and reserving regulations, as well as detailed and often time-consuming product approval processes.

CI products were introduced to Hong Kong in 1986, soon after in Singapore and Malaysia and in Taiwan during 1989. In Taiwan the first standardisation occurred, not driven by distribution or consumer concerns, but simply because of the approval mechanism turning a once admitted policy wording into an industry standard. These same definitions held up until recently when, after a review process lasting more than six years, the Taiwan regulator agreed to a new set of standard definitions, which now encompass seven severe illnesses (starting 1 January 2016) and seven minor ones (tiered benefit – starting 1 April 2016).

Objective of standardisation

The over-arching objective is to improve clarity without changing the essence of the current definition. This can be achieved by defining the event and, where possible, specifying the cause(s) of the event and clearly listing any exclusions. A new definition should state specifically the claims admission criteria to ensure consistency among insurers and any review of wordings should be based on medical advancements.

Clear and consistent description of CI coverage across the industry enhances consumers’ confidence in products. It allows people to compare price and other value-added benefits instead of the technical merits of different definitions. Supervisors find it difficult to understand the differences between various definitions of the “same” disease or event. As supervisors move towards consumer protection and away from regulating companies, standard definitions make their task simpler. Common wordings also make life easier for sales agents who can now avoid contentious discussions about whose definitions are better.

Standard definitions bring industrywide consistency to claims assessment by reducing incidences where one insurer pays a CI claim while another rejects it due to wording differences. Standardisation helps build a platform from which the true incidence of CI conditions in the insured population can be accurately assessed. It aligns the key existing definitions with advances made in medical technology and clinical practice, and addresses areas of practical constraint based on insights gained from past experience.

Scope of standardisation

The scope varies from market to market. In 2002, for example, the Life Insurance Association of Malaysia introduced standardised definitions for 38 diseases. In 2003 the Life Insurance Association of Singapore (LIA) introduced standardised definitions for 37 diseases. In both markets the standardisation exercise came with a limitation of the maximum number of diseases to be covered: 30 in Singapore (which were selected from the list of 37 diseases) and 36 in Malaysia. When the LIA consulted with the Competition Commissioner of Singapore for its 2014 review of the definitions, however, the Commissioner ruled that the limitation of diseases was anti-competitive; thereby repealing the cap in the number of conditions an insurer can cover under its traditional CI product.

As it was, the industry had already started bypassing this element by offering tiered benefits outside the scope of the standard definitions. In April 2007 the China Insurance Regulatory Commission, in co-operation with the Life Insurance Association of China, introduced standardised definitions for 25 diseases. In 2009 the last to act was the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), which embarked on a standardisation project that resulted in standard definitions for 11 diseases promulgated by the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India in 2013. India has recently (as of July 2016) updated its set of standardised definitions, revising some of the existing 11 definitions (especially Cancer, Heart Attack and Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting), as well as expanding the standardised definitions by 11 additional diseases.

How does a review work?

This is a most critical issue. The LIA Singapore has embedded a review process in its guidelines, stipulating that “The industry will review the LIA’s common definitions for continued relevance once every three years.”1 As the Taiwan example shows, where there are standard definitions, reviews can be delayed. The same seems to be happening in China, where a significant increase in thyroid cancer claims gives evidence of a cancer definition with insufficient exclusion wording.

There has to be agreement on the review process, including:

- The project management (deadlines, correct briefing of participants about the aim of the exercise, guidelines for review process)

- Involvement of all risk takers, i.e. including reinsurers

- Involvement of various disciplines (not only clinicians but also actuaries, underwriters, claims assessors, etc.)

- Involvement of an experienced Insurance Medicine-trained medical doctor who is able to differentiate the clinical requirements of the definition as compared to the product requirement

- Focus on the core diseases but not neglecting the other definitions (which can be just as costly)

- Agreement on standard definitions and possibly on the maximum number of covered diseases/events (However, see the latest Singapore competition ruling.)

- Agreement on other policy aspects (e.g. the LIA in Singapore includes an agreement on a 90-day waiting period for major diseases, as follows):2

- “To address the concern of anti-selection, insurers must adopt a 90-day waiting period for the severe stage of following five CIs:

- Major Cancers

- Coronary Artery By-Pass Surgery

- Heart Attack of Specified Severity

- Angioplasty and Other Invasive Treatments for Coronary Artery

- Other Serious Coronary Artery Disease”

Who should work on/review standard definitions?

The working committee should be kept to a minimum number of participants; however, there should be equal participation of all the direct insurance companies as well as all the reinsurers who are involved in covering this product. Equally important is the participation of the non-life companies that may sell similar products. It is also important to brief all involved parties (insurance association, regulator, etc.) regularly and properly about the project, as the final decision makers (e.g. CEOs) are typically not in a position to make an educated decision. Often the regulator is represented; in Singapore the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) makes the final decision.

How does it work with tiered definitions?

In South Africa standard definitions for tiered benefits were already introduced in 2008, while they have only been addressed fairly recently in Asia. As mentioned, since 1 April 2016 in Taiwan, there are now seven standard definitions for tiered benefits. In Singapore the LIA chose not to address this aspect at this time, saying, “The LIA’s common definitions describe the respective medical conditions at the ‘severe’ stage. With reference to the LIA framework, other than the ‘severe’ stage for 37 medical conditions, all other medical conditions and their stages of illness progression are not defined by LIA.”3

What was the impact on the CI market in regions where definitions were standardized?

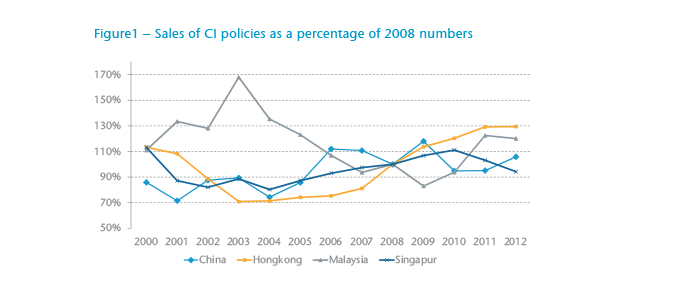

Sales – Figure 1 shows the number of new policies sold as percentage of 2008 numbers. Standardisation seems to have had little impact, as Hong Kong is holding up pretty well without standardised definitions.4

Customer retention – Persistency in most Asian markets has improved markedly in recent years: first-year persistency tends to be around 90%, increasing to 95% (Hong Kong), 96% (Malaysia), 97% (China) or even 98% (Singapore) after five years. This is largely driven by product design, almost all being level premium, often with a limited premium payment term.

Pricing – Standardisation has had no major impact on pricing. In markets such as Taiwan or China, where interest rates and other pricing parameters are prescribed, pricing differentiation has not been relevant. In other markets, the addition of minor benefits has diluted the standardisation effect.

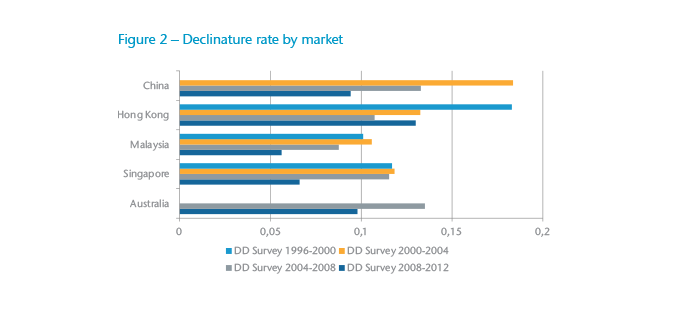

Claims – In markets with standardised definitions, the number of repudiated claims has decreased significantly. As previously suggested, standardised definitions help agents and consumers to have a better understanding of the coverage, and possibly play a role in reducing repudiated claims by reducing the number of claims requests that do not meet the definition.

In China the October 2009 introduction of a two-year incontestability clause (which already existed in Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore) may have added to the improvement.

Summary

The main points in favour of standardisation include:

- Scope of cover is the same across companies eliminating the need to go into details.

- Claim payments are consistent so industrywide incidence rates are more meaningful.

- Sales agents need not know the difference in medical definitions from one company to another.

- Consumers know where they stand and understand what is covered.

- Companies may abandon competing on multiple and rare diseases that are difficult to define and often misunderstood.

- Bad press coverage will be avoided.

Yet standardisation may restrict competitiveness and the response to advances in medical diagnostics/treatment could be slower. There is one further caveat – as confusion may still arise if a person is covered by different policy generations that use distinct wordings. The Singapore LIA addresses this in this way: “Each CI claim will be assessed fairly according to diagnosis of insured’s critical illness and CI definition stated in the contract. The insurer will pay the claim based on the policy contract that was issued at the time. If one has a few policies bought over different periods, the definition of the condition may be different and therefore the claim will be administered according to the individual policy.”5

Standardising CI definitions is largely helping the industry make a complex product more transparent and more acceptable to consumers. It is of vital importance, however, to agree on a regular review process that is conducted by experts from different areas and that takes into account actual experience and anticipates the impact of latest medical, legal and other developments to ensure sustainability of the product.