-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Insurers in Quest of the Perfect Heart Attack Definition

July 17, 2016

Andres Webersinke

Region: Australia

English

Earlier this year Australian life insurers were in the spotlight, allegedly using “out-dated” medical definitions in their Trauma (Critical Illness) policies. As a consequence, many insurers reviewed their medical definitions and claims management practices, with particular focus on the definition for “heart attack”.

The idea of Trauma insurance is simple. Insurers promise financial relief when the insured suffers a medical condition that is relatively common, generally recognised and dreaded (hence the earlier name of Dread Disease insurance), such as cancer or heart attack.

In the 1980s when Trauma insurance was first introduced, these conditions were easy to define. Cancer was either malignant and covered, or benign and excluded; cardiac biomarkers reliably assisted in the diagnosis of a heart attack. Grey areas were minimal.

This has changed dramatically in just a couple of decades. The goal of treating patients as early as possible resulted in ever-improving diagnostics, changing definitions and classifications of medical conditions. In some instances clinicians themselves discuss “over-diagnosis” – for example, the need to consider using the term “cancer” more sparingly.1

It is not surprising that insurers struggle to define conditions covered under a Trauma policy. These conditions need to be robust enough to offer sustainable premium rates and objective for claims assessment, but still offer transparency to customers and advisers concerning the level of cover.

Although medical definitions are part of an insurance contract, suggesting an absolute meaning, the insurer’s claims philosophy must address questions such as, “What is intended to be covered?” or “Is the condition covered even if not all claims criteria are fully met?”

In the case of heart attacks, it is tempting to follow the clinical definition. But this still requires interpretation, not only by insurers but also clinicians.

Clinical diagnosis and definition of myocardial infarction

Clinicians are challenged when a patient arrives at an emergency department with symptoms of an acute coronary syndrome (ACS – a range of disorders caused by the same underlying problem, including heart attacks) but may well turn out to be indigestion only. A quick diagnosis with the aim of providing the best treatment, and minimising waste of resources and waiting time for patients, is critical. This is often based on symptoms and more or less abnormal Electrocardiography (ECG) results.

To achieve this, clinicians need a reliable test that helps them to quickly rule out a possibly life-threatening condition, and cardiac troponin (cTn) has been recommended as the preferred biomarker for this purpose. Tests to detect the level of cTn in blood have evolved over the last 20 years. They have become increasingly sensitive, i.e. being able to detect smaller amounts of cTn. But this comes with a somewhat reduced specificity, i.e. where cTn is also detected in patients with other cardiac and non-cardiac conditions.

The key criterion of the clinical definition is the “detection of a rise and/or fall of cardiac biomarker values [preferably cardiac troponin (cTn)] with at least one value above the 99th percentile upper reference limit (URL)”.2

This requirement looks objective on the face of it. However, this seemingly simple requirement has limitations and the level of interpretation that is required before an MI can be finally diagnosed is not insignificant.

Globally, clinical experts agreed on a universal definition for the diagnosis of a myocardial infarction (MI), also known as heart attack. The third universal definition was published in 2012 and consists of 420 words. Life insurers covering heart attack under a Trauma policy primarily cover an acute (sudden onset versus prior or silent) MI but not all types of MI (e.g. MIs associated with a surgical procedure, such as an artery bypass grafting).

The most recent (fifth) generation of cTn assays (tests), also known as high sensitive cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) assays,3 have been in use since 2010 in a number of hospitals in Australia and New Zealand. Interestingly, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not yet cleared them for clinical use.

In patients with MI, levels of cTn rise rapidly. With an hs-cTn assay, troponin elevation can be detected earlier, usually within one hour after symptom onset instead of three to four hours with an earlier generation assay. An hs-cTn assay is classified “high sensitive” if it detects troponin in more than half of healthy individuals.

Key issues with troponin and the universal definition of heart attack

Changing levels of troponin is a critical criterion of the universal definition of heart attack. Several key issues that insurers need to keep in mind when relying on this biomarker for the assessment of a lump sum claim are listed below, and are further discussed in separate text boxes.

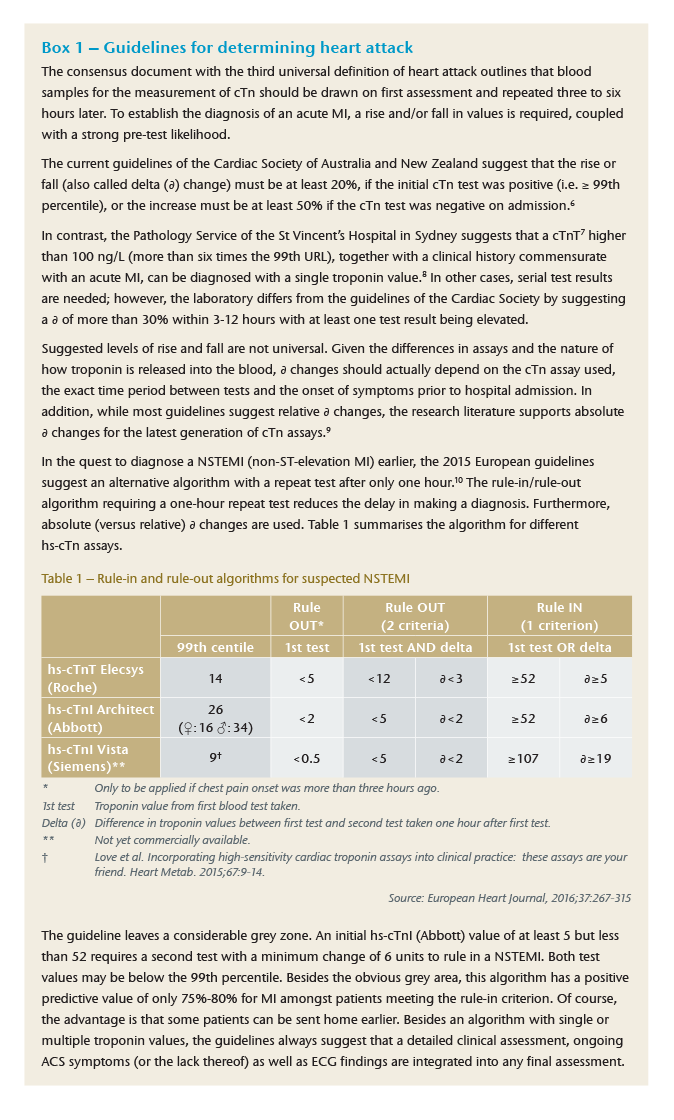

Guidelines

The universal definition of heart attack does not exist in isolation. Clinicians use guidelines to diagnose and utilise the right treatment option. Guidelines differ from region to region and include specific algorithms to assist clinicians in predicting with some certainty whether a patient suffers a heart attack or not. These algorithms change with new cTn assays and research findings. [See Box 1]

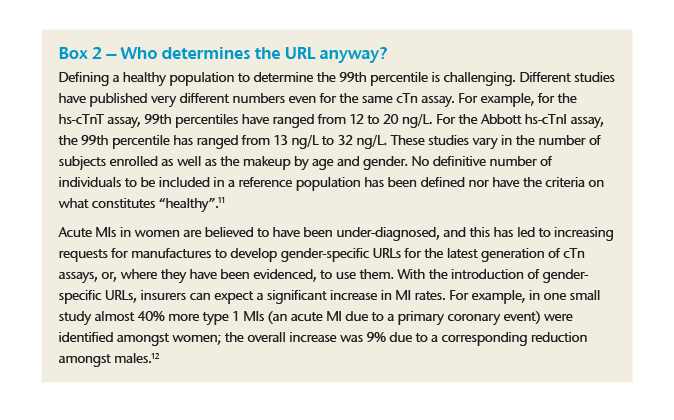

Upper reference limit

The 99th percentile of an upper reference limit (URL) depends on the chosen assay and depends on how the manufacturer of the assay defined the healthy reference population. Differences by gender and race may exist. Also, different studies recommend different URLs for the same assay. In other words, clinicians and insurers depend – to some degree – on the choice of the assay used and which study the laboratory applies at any one time. Simple cut-off levels may thus be difficult to justify in all cases. [See Box 2]

(In)significance of a troponin value

In some emergency scenarios (e.g. when a so-called ST-elevation MI (STEMI) is suspected) troponin values are less relevant or even required for a diagnosis. Some algorithms also suggest a single high troponin reading (instead of a rise and/or fall). In these cases where a clinician does not require a rise and/or fall of cTn in order to initiate treatment to prevent an acute MI from further damage, insurers have to consider the overall clinical presentation and treatment provided. [See Boxes 1, 3 and 4]

Pattern of rise and fall

Following a cardiac injury, cardiac troponin is released into the blood. Troponin levels increase within a few hours after the onset of damage, peak after 24-48 hours and return to normal over a period of several days. Consequently, the clinician and the insurance claims assessor should bear in mind such factors as time interval from symptom onset to hospital admission and first cTn test, time interval of further cTn tests and assay used. Even if an algorithm suggests a high predictive value, predictability can be influenced by late admission to hospital, old cTn assays or the use of point-at-care devices (versus laboratory analysis). Insurers using definitions requiring a minimum cTn elevation should include an alternative requirement or otherwise address the fact that cTn rises and falls in a particular pattern.

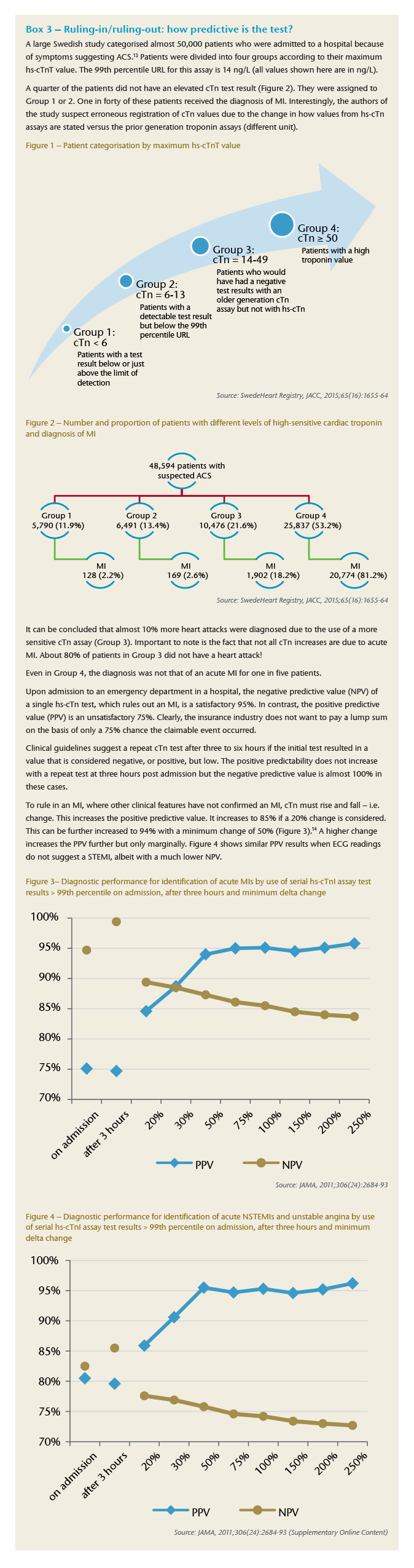

Test accuracy

Every test has a particular sensitivity (identifying a condition amongst diseased people) and a particular specificity (producing a negative test result in a healthy person). The fifth generation cTn assay is particularly sensitive and thus useful in an uncertain emergency situation where the focus is in ruling out a heart attack as soon as possible – i.e. achieving a high negative predictability. Insurers, however, want to rely on a test result that has a high positive predictability. [See Box 3]

No troponin information

Besides the universal definition, the WHO has also weighed in with a definition of heart attack. It suggests that whenever there is incomplete information on cardiac biomarkers and other diagnostic criteria needed, the term MI should be used if both of the following criteria are present: a) symptoms of ischaemia and b) development of unequivocal pathological Q-waves (on the ECG).4 This part of the WHO definition could be considered alongside the third universal definition if biomarker results are not available or valid.

How to solve this conundrum?

In an earlier issue of Risk Matters Oceania, Gen Re addressed the question of when is a heart attack a heart attack, and the fact that most insurance policies are likely to be out of step with the clinical heart attack definition.5 However, this article highlighted that the clinical definition is not the silver bullet answer in terms of objectivity and transparency. The purpose of the universal definition is to make the right decision in an emergency situation.

A Trauma product, on the other hand, intends to offer a single lump sum benefit when the customer’s health has been compromised and permanently impaired, reducing the insured’s life expectancy or the ability to work or demanding significant lifestyle changes. Consequently, the heart attack definition for insurance purposes should not be based solely on a diagnosis made during an emergency situation. In both Australia and New Zealand, the maximum sum assured under a Trauma policy can be in excess of AUD 2 million (respectively NZD 2 million) or an equivalent USD 1.5 million. Large benefit amounts should be based on the underlying medical condition and damage this has produced. This would be more consistent with other Trauma conditions.

Furthermore, the advances in diagnostics have resulted in more minor heart attacks being diagnosed. This trend can be expected to continue.

To offer affordable Trauma policies, insurers should consider paying significantly less than the full sum assured for heart attacks based on diagnosis alone.

Additional benefits can be considered when the insured is required to undergo further medical treatment, such as angioplasty or bypass grafting surgery as it approximates the extent of the underlying disease. This can be further differentiated by the number of coronary vessels treated and, in the case of an angioplasty, whether a stent is placed or not.

Alternatively or additionally, the benefit level could be tiered depending on the impact the heart attack has had on the heart’s capacity to pump blood through the circulatory system (using the ejection fraction).

While the idea of Trauma insurance is simple, the underlying benefit trigger is complex. Insurers cannot make simple what is complex in nature. There are individual situations for which a definition may not be perfect. Insurers require a claims team that can understand the clinical presentation of a heart attack, knows local guidelines, communicates well with the Chief Medical Officer and the treating clinician, is prepared to go beyond the absolute meaning of a definition and uses all information presented in a holistic approach.

Product actuaries, too, need to appreciate weaknesses of a clinical definition when pricing and designing an insurance product.

Finally, just as the patient must have trust in the treating doctor, the insurance customer should have trust in the insurer assessing claims fairly. Building trust goes beyond the wording of a medical definition.

Chief Underwriting Officer and Head of Research & Development – Life & Health

See All Articles