-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

How Annuities as Standard Compensation in Italy Could Affect the Insurance Industry

November 25, 2015

Stefano Colombo,

Lorenzo Vismara,

Alessandro Simonato

English

Italiano

On 27 January 2015, the Court of Milan (1st Civil Division, presiding judge Ms Martina Flamini) issued a judgement that created great interest and lively debate. For the first time, a division of the prestigious Milanese court used the instrument of the lifelong annuity – provided for under Article 2057 of the Italian Civil Code – for the payment of a significant share of the compensation awarded in a case of medical malpractice.

This article will seek to examine the case from the viewpoint of insurance and reinsurance, illustrating the possible scenarios for case management. We consider it important to point out from the outset that during the course of the ten months since this ruling was issued, as far as the authors are aware, no cases have been decided in a similar manner either by a court ruling or when liquidating damages by companies in “out-of-court” negotiations.

The facts of the case

The court was required to rule on the consequences of a total thyroidectomy operation, following which the patient, a 40-year-old doctor, suffered extremely serious injury resulting in a spastic quadriplegia, which was assessed to have caused a 90% impairment of her psychophysical integrity. Having established the liability of the doctors responsible for the patient’s care during the post-operative stage, and drawing on the findings of the court-appointed technical expert, the court described the dramatic situation of the injured party as follows: “Total dependence of the patient for all personal needs, who requires round-the-clock personal assistance … the need for assistance demands the presence of a person who sleeps at the patient’s home from Monday to Friday, in addition to the presence of two people with a 48-hour shift on Saturdays and Sundays; a carer who is present throughout the day is then also assisted by a second carer for three hours per day. The practical objective is not the stimulation of the patient, but the maintenance of her residual efficiency …”.

The court-appointed technical expert went on to set out the requirements in financial terms of this type of assistance: “ … The following annual expenses may be envisaged: €50,000 for generic home care, oscillating by around ten percent; €10,000 for costs of transferring the claimant; €3,000 for the acquisition of pharmaceuticals not provided by the national health service; €6,240 for physiotherapy costs, insofar as not covered by the national health service; and the initial setting up of a medication room and the fitting out of the room for physiotherapy equal to €15,000”. Following observations made by the claimant, this amount must be increased by €4,000 per year, which is necessary in order to “cover replacements for public holidays and days on which the care providers are on holiday or unwell”.

The amount identified as necessary for providing the assistance specified in the court-appointed expert’s report is thus specified as totalling €85,000 per year.

There is only one crucial aspect in which the court departs from the findings made by the court-appointed technical expert: life expectancy. The expert had in fact concluded his analysis with a forecast that the injured party would survive for 10 - 12 years.

However, the court decided not to endorse this assessment, arguing that “without providing any specific indication, the court-appointed technical expert concluded that, on the basis of the state of the claimant’s health and the seriousness of the injuries suffered by her, she could be expected to survive for between ten and twelve years. However, this fact cannot be endorsed as the following indications suggest the opposite: since 2008, and thus for more than five years, the claimant has not suffered any relapse; BC has been subject to very tiring transfers and surgical operations abroad (involving the upper right limb, the left limb and the lower right and left limbs), the results of which have been positive (which is not disputed); since 2008, there has been no deterioration from which it may be inferred that the claimant’s conditions are destined to worsen within the limited period of time indicated by the court-appointed technical expert; in the last three years, she has not required any further admission to hospital for complications; she is provided with excellent assistance, which cannot be overlooked when forecasting his future life expectancy”. On the basis of these arguments, and “considering that it is impossible to objectively establish a presumed life expectancy of the claimant”, the court thus concluded that the injured party should be compensated in relation to the element of damage relating to the costs of care and assistance and to pecuniary loss resulting from the specific lost earning capacity of €85,000 and €60,000 respectively, resulting in an overall annuity of €145,000, to be adjusted in line with the ISTAT (Italian National Institute for Statistics) index of consumer prices for the families of production workers and office workers.

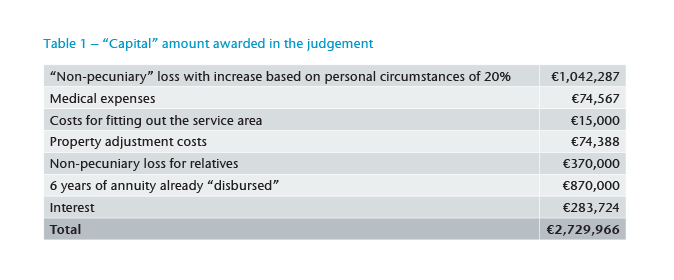

In addition to these heads of damage, the judgement also awarded the “standard” heads of damage specified in the Court of Milan Tables, as set out in Table 1.

Compensation for losses by way of a lifelong annuity

The viewpoint of the (re)insurer

The use of compensation in the form of an annuity should not be entirely unknown under Italian law, considering that Article 2057 of the Civil Code expressly provides that “when the personal injury is permanent in nature, the award may be made by the court, taking account of the circumstances of the parties and the nature of the loss, in the form of a lifelong annuity”.

Despite the clear provisions of the Code, which has been unanimously interpreted to the effect that such a remedy may be used to compensate both loss of income and any expenses that the injured party may be required to bear regularly on an ongoing basis, and has also been asserted in a renowned judgement of the Court of Cassation1, it has hardly been applied by the courts “given that the injured parties prefer an award capitalised at current values”. In fact, within the case law of the merits courts, there are a small number of isolated precedents which, above all, have in all cases led to the award of annuities of a rather modest amount (see most recently, Court of Trieste, judgement of 5 April 2012, annuity of €18,000 for pecuniary loss resulting from inability to work, Court of Genoa, 3rd Division, judgement of 15 June 2005, annuity of €30,000 resulting from all of the items of permanent loss awarded with the exception of moral damage, Court of Lodi, judgement of 8 May 2013, with the award of an annuity of €12,000 for pecuniary loss resulting from the inability to work).

Against the backdrop of the framework set out above, it is clear that the ruling of the Court of Milan was exceptional in nature; in fact, it was the first case in which the instrument of damages in the form of an annuity was used to the full – moreover awarding a very high amount – in order to compensate all heads of damage directly attributable to the fact that the injured party is still alive, considering the uncertainty concerning her life expectancy which, due to scientific progress, tends to increase constantly.2 It is of course also necessary to note the prestige of the court along with the significant coverage that the specialist and generic media have given and are continuing to give to the case.

Our analysis from the viewpoint of (re)insurance cannot neglect, in the first case, to provide an assessment of the instrument of damage, its efficacy and the way in which it is managed – where an insurance company is involved in similar cases; where it is obliged to guarantee each year (or month, depending upon the interval at which the annuity is paid) the amount awarded by the court – as duly revalued each year.

In the first place, it must be stressed that compensation in the form of an annuity is the most prevalent form of compensation in many European markets. In France, the United Kingdom and Germany – considering only the principal markets – cases involving serious personal injury are always awarded following an extremely careful and precise determination of the injured party’s needs for assistance as well as the pecuniary losses resulting from the injury. These amounts are then transformed into annuities, the levels of which may even be quite high. Many observers regard the use of this form of compensation as one of the possible causes of the significant increase of the amounts awarded for major injuries in those countries – above all with regard to the exposure of insurers.

It will come as no surprise that this form of compensation has become the norm in other systems. In fact, the payment of an annuity is regarded as the most appropriate way of ensuring that delicate, if not dramatic, situations resulting from catastrophic physical injury are compensated adequately and on an ongoing basis at amounts that are not subject to the risk of dispersal within very short periods of time due to inadequate management by the relatives or curators of victims. Another problem to which injured parties and their families may potentially be exposed, which is significantly reduced by compensation in the form of an annuity, is what results from the possibility that the capital amounts, which were deemed to be appropriate for that purpose at the time compensation was calculated, subsequently proved to be insufficient due to an unexpected extension in the survival of the injured party or significant inflation.

Naturally, the opposite scenario may arise in the specific individual case. Indeed, cases may arise in which considerable compensation awarded in the form of a capital payment is then “enjoyed” by the heirs of the injured party in the event that the latter dies shortly after the settlement was finalised.

Payment in the form of an annuity evidently scales back most of the problems set out above, and in some cases entirely removes any margin for uncertainty, at least as far as the injured party is concerned.

Insurance management

On the level of insurance management, in the event that the judgement under examination were to be complied with by the claims office of a company, various problems would need to be examined, some of which would have a certain financial significance.

The first crucial question that will need to be addressed would concern the estimate of the amount to set aside to the claims reserve. Having established the need to calculate the “last” cost of the claim, Article 27(7) of ISVAP [Italian Supervisory Body for Private Insurance] Regulation No. 16 of 4 March 2008 provides that “where undertakings are required in the event of a claim to pay compensation in the form of an annuity, they shall assess the claim reserve to be set aside on the basis of recognised actuarial methods”.

Naturally, the first step that must be taken when quantifying the technical reserve to be set aside involves a calculation of the capital amount awarded in the operative part of the judgement. Our calculation results in the amounts highlighted in Table 1.

It will then be necessary to quantify on the basis of “recognised actuarial methods” the amount that needs to be set aside in order to guarantee the annuity of €145,000 (as revalued from year to year) for the full residual lifetime of the injured party.

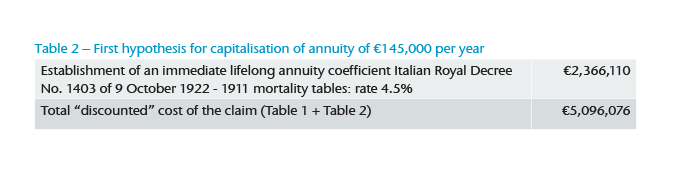

It is evident that, when discounting the financial commitment resulting from the payment of compensation in the form of a lifelong annuity, we could be led to use the “classic” instruments normally used when awarding damages, which provide for the use of the capitalisation tables contained in the Italian Royal Decree No. 1403 of 9 October 1922. Accordingly, the current amount obtained by using this instrument and the coefficients contained in it is displayed in Table 2.

Although the financial result already gives a tangible idea of the significant magnitude resulting from the capitalisation of such significant amounts compensated in the form of an annuity, the parameters used clearly demonstrate that they are inadequate for assessing whether the reserve set aside on the basis of mortality tables that are more than 100 years old and rates that are entirely inadequate with regard to the current economic climate is appropriate and correct from an actuarial point of view.

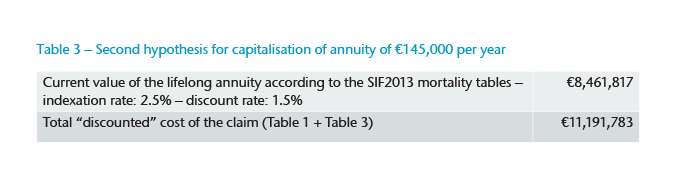

In accordance with the above, and given the need specified in the legislation to assess “the claims reserve to be set aside on the basis of recognised actuarial methods”, it is evident that, in cases similar to the present case, it is necessary to rely on actuarial functions and instruments. This approach will necessarily result in the use of updated mortality tables that are, as far as possible, tailored to the level of severity of the injured party and financial parameters appropriate to the current economic climate, and will be sustainable over the long term in line with the life expectancy of the injured party, which at the present time – by the express assertion of the court – is unknown. It is important to point out that the current value of the lifelong annuity is extremely sensitive to the mortality assumption and interest rate used. For example, in the event that the condition of the injured party were considered to be equivalent to that of a healthy individual, and within a scenario of interest rates more in line with current levels, this would result in the values stated in Table 3.

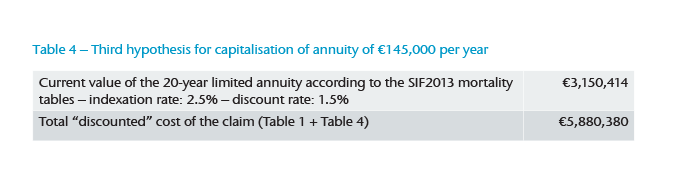

If, on the other hand, there were indications suggestive of a shorter life expectancy (for example, by 20 years), the current value would be that stated in Table 4.

This last approach is naturally open to the possible risk that the injured party may survive for a period in excess of 20 years, de facto rendering the reserve set aside on this basis insufficient in order to cover the entire future commitment.

It is thus evident that the management of such a case within an insurance company – a scenario that is rather specific given the case law decision being discussed here and the possible application also to such cases as claims relating to road traffic accidents, the cover limits for which are now very significant – would also result in the involvement in the claim management process of experts capable of expressing further assessments, such as those mentioned above concerning the actuarial methods to be applied and the medical assessments that may indicate the prospects for survival of the injured party in each specific case. In some European markets, the claims offices often combine the results of the actuarial approach and the medical assessment in order to provide an estimate that is as sustainable as possible over the medium term concerning the prospects for the reserve set aside maintaining its value.

Considering the variety of approaches potentially possible within a case hypothetically equivalent to that ruled on by the Court of Milan, our assessment would result in the setting aside of a reserve that represents a prudential middle way between the scenarios displayed in Table 3 and Table 4, at least during an initial stage of the claim in which the assessments concerning the life expectancy of the injured party are rather difficult to make.

In the light of the above, it is necessary to provide two conclusive considerations concerning the management of these types of loss from an insurance perspective.

In the first place, it should be pointed out that the solution proposed by many commentators, whereby it is supposedly “easy” to pay compensation for a lifelong annuity by transferring a “single premium” – equal to the capitalised value of the annuity calculated according to the “classic” methods set out in Table 2 – to the life branch of a company in respect of the establishment of a specific product suited to that purpose, is rather difficult to pursue in reality. In fact, the life branch is based on mathematical and actuarial methods and on the mutuality principle, the sustainability of which results from the ability to dispose of a large portfolio of similar risks that enable specific updated statistical parameters to be used. The Italian market, within which compensation in the form of an annuity is still practically unknown, does not offer a sufficient number of significant cases to pool the risk of a product similar to that proposed here. It is thus evident that any life sector of an insurance company that was required to create a product suitable for guaranteeing an annuity in the manner specified in the judgement under examination here would have to demand as consideration a single premium, in addition to safety margins, that could probably result in an amount very close to that stated in Table 3. This is why in all compensation systems in which the annuity is the most widespread in cases involving major injury, the management is always conducted within the non-life branch and why no life products are created, in spite of the fact that in other countries annuity cases are certainly more numerous, although most likely insufficient in order to create a reliable and sustainable statistical basis.

It should also be pointed out that, in addition to the problems mentioned above in relation to reserves, it is necessary to add others of a “management” nature associated with that form of compensation. Depending upon the regularity of the annuity, it will in fact be necessary to check on a monthly or annual basis that the recipient is still alive, to update the amount in line with inflation and to arrange for the actual payment of the amount itself. In markets such as the French market – where annuities are widespread – these requirements of an administrative nature have resulted in the creation of several departments within claims offices that deal solely with the administrative management of annuities already disbursed.

Reinsurance management

All of the critical aspects that have been highlighted above also have a substantial impact on reinsurance contracts relating to general liability risks and, on a more significant scale considering the size of the branch, also to motor vehicle liability.

Limiting ourselves to Excess of Claim agreements, which comprise the majority of those in existence for liability risks, a significant development in compensation in the form of annuities would result in coverage scenarios drastically different from those to which we are accustomed, as we have observed in the markets in which this form has become widespread over recent years – mainly the UK and France.

Essentially, given the need to establish the last cost reserve according to recognised actuarial criteria, this would result in a significant increase in the number of claims to falling under the Excess of Claim cover, and consequently an increase in the reinsurer’s commitment.

Current practice is for the insurance company to pay out the claim to the injured party in one single instalment (“amount capitalised at current values”), after which it charges the reinsurer for the part in excess of the monetary limit (retention) specified in the reinsurance contract.

Under a scenario in which an indexed lifelong annuity is awarded, the number of claims and their amounts will have a much greater impact on reinsurance contracts compared to the present, even though they are subject to the application of the Index Clause.

The text of the contract will therefore have to be reviewed in order to deal with this change by stipulating that the parties shall agree upon both the actuarial methods to be applied in order to determine the last cost as well as the arrangements for sharing that cost between the ceding company and the reinsurer.

As regards this last aspect, we can state that there are essentially two methods.

Under the first, the reinsurer starts reimbursing the ceding company when the total amount of the annuities and other payments made to the injured party exceeds the priority specified in the Excess of Claim.

The second, which is more common in France, is based on the direct participation of the reinsurer in the payment of the annuity in the same percentage resulting from the ratio between the priority and the discounted cost of the claim. In other words, if the discounted cost of the claim is 3 million euros and the priority under the contract is 2 million euros, then the reinsurer will immediately pay one-third of the annuity even if the total amount paid does not exceed the priority.

It is evident that the cost of the reinsurance premium will also differ, depending also on the different cash flow structure.

In any case, the contracts also contain clauses providing for a review of the terms, which may be activated in the event of changes in exogenous factors such as interest rates, or cut-off clauses that cancel the commitments after an agreed number of years.

However, perhaps the choice of reinsurer is the most critical factor for a ceding company within a scenario involving compensation in the form of an annuity.

If liability coverage is already defined as long-tail business, where the reliability over time of the reinsurer is fundamental, in cases involving very long-term annuities, this aspect becomes vital for granting future sustainability and effective cover, and thus ultimately for protecting the original insured.

Alongside the rating, specific technical expertise and support in the management of the claim, shall constitute the pillars on which the relationship between the ceding company and the reinsurer has to be founded, which in this case more than in any other can be defined as a genuine partnership.

Endnotes

- Court of Cassation, 3rd Division, Judgement No. 24451 of 18 November 2005.

- Recent studies based on statistical statistics indicate an average life expectancy of around 20 years for the case under examination. Cf. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/.