-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Obesity in Mexico – The Impact on Health Insurance

November 09, 2014

Janice Mina

Region: Latin America

English

Español

A considerable increase in the global prevalence of overweight and obesity has been observed over the last three decades. The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined “overweight” as a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 25 and “obesity” as a BMI greater than or equal to 30. According to WHO data, obesity rates have more than doubled since 1980. In 2008, 1.4 billion adults over 19 years of age were overweight, of which more than 200 million men and nearly 300 million women were obese. Furthermore, in 2010 approximately 40 million children were overweight.1

Mexico has experienced one of the fastest increases in the prevalence of excess weight and comorbidities.2 The increase has occurred in all age groups and in both rural and urban areas of the country. Obesity is now recognised as a public health problem. Although in the past considered almost exclusively a problem of developed countries, obesity incidence has experienced an abrupt increase in developing countries.

Obesity is linked with more deaths than malnutrition and some infectious diseases. This, coupled with growing levels of obesity in children, has prompted the WHO to declare the condition a new epidemic for the 21st century. This article looks at the obesity epidemic from the perspective of Mexican medical expenses and disability insurance.

Mexico in a global context

From 1988, which was the first year the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) was conducted in Mexico, until 2012, the prevalence of “overweight” in women of 20 to 49 years of age increased from 25% to 35.3% and “obesity” from 9.5% to 35.2%. This represents an increase of 41.2% in the prevalence of overweight and of 271.5% in obesity.3 Mexico is second only to the US in having the highest rate of obesity in adults (Table 1).

Mexico currently holds first place in the world for child obesity.4 The NHANES data shows that from 1998 to 2012 the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children under five increased from 7.8% to 9.7%. The increase was higher increase in the north of the country where the prevalence was 12% in 2012 – 2.3 percentage points above the national average. In 2012 the combined national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children aged 5 to 11 was 34.4% (girls 32%, boys 36.9%). For adolescents the figures were similar with 35% overweight or obese. Meanwhile the national prevalence in adults was 73.9% (women 82.8%, men 64.5%).

Obesity is a multifactorial disease. Sedentary life, high-calorie diet, cheap junk food, a lack of nutritional counselling and genetics go some way to explain the increased prevalence of obesity in Mexico. Over the last decade, the middle class in Latin America has increased by 50%.5 It has become common to eat in fast-food restaurants and to consume carbonated beverages. The relative price of soft drinks fell fuelling a 60% increase in consumption from 1989 to 2006. Mexico is now the largest consumer of soft drinks in the world, with an average of 163 litres per person per year. The greatest consumption is in the 12-to-39 age group and it is especially high in the 19-to-29 age group.6

Impact on mortality and morbidity

Obesity is a risk factor in the development of chronic degenerative diseases, including heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, sleep apnoea, liver cirrhosis and musculoskeletal disorders, particularly osteoarthritis. WHO data links overweight and obesity to 44% of diabetes cases, 23% of ischaemic heart disease cases and between 7% and 14% of cancers such as breast, uterine and colon cancer.7

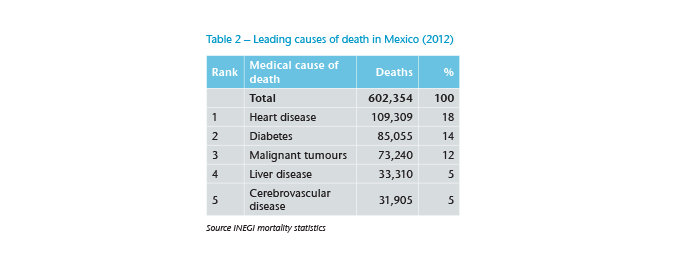

Mexico has undergone an epidemiological transition. In the early 1950s pneumonia, gastroenteritis and other communicable diseases were the major causes of death. These causes were displaced by non-communicable diseases and injuries in the 1990s. From 1950 to 2000, the percentage of deaths resulting from intestinal infections decreased from 14.3% to 1%, while the number of deaths from heart disease quadrupled (from 4% to 16%).8 Diabetes as a cause of death has moved from top 20 in the 1960s to the top 10 in the past two decades.9 Since 2004, diabetes has been the second cause of death in Mexico with 85,055 deaths per year (see Figure 2).10

While it is true that the combined prevalence of overweight and obesity in Mexican adults is higher in women than in men, the life expectancy of obese women is not necessarily less than that of obese men. This is primarily due to the distribution of fat; while in the majority of women fatty deposits are located in the femoral region, in males these deposits are more frequently found in the abdominal and visceral areas, and the accumulation of fat in these regions represents the greatest risk factor for the development of certain cardiovascular diseases.

Studies show obesity reduces life expectancy by an average of seven years.11 That obesity is increasingly affecting children is worrying as they are more likely to be obese in adulthood, compared to non-overweight children, and are more likely to develop diabetes and cardiovascular disease at an early age. In turn, these conditions are associated with an increased chance of disability and premature death.12 Should the trend continue, new generations of Mexicans could experience, for the first time, a lower life expectancy at birth than their parents.

Morbidity from diabetes showed a steady increase until 1998, ranking 10th among the main causes of morbidity in Mexico in 2005. Diabetes occurs at earlier ages in Mexico compared to other countries. The Ministry of Health estimates almost 65% of Mexicans who have diabetes also have hypertension, increasing their risk of stroke. Diabetes is the leading cause of blindness in adults and is responsible for 60% of end-stage renal failure cases. Diabetic ulceration is one of the leading causes of hospitalisation in Mexico with 70% of cases resulting in amputation.13 Overweight and obesity also significantly increase the demand for health services and, therefore, consume a significant portion of the budget allocated to this area. It is estimated that the cost of obesity in 2008 was MXN $67 billion, and based on the observed trend, it will reach between MXN $151 billion and MXN $202 billion by 2017.14

Impact on insurance

The penetration of insurance in Mexico, as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), is about 1.9%.15 According to the Mexican Association of Insurance Institutions (AMIS), only 13% of the economically active population has life insurance and about 6.5% of the total population has major medical insurance coverage.16

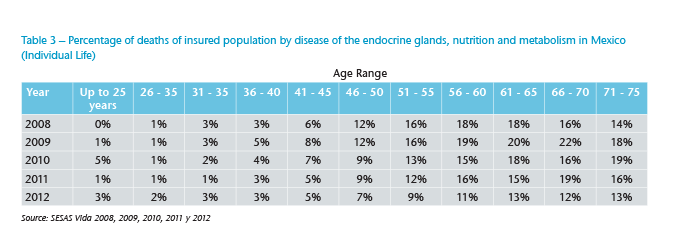

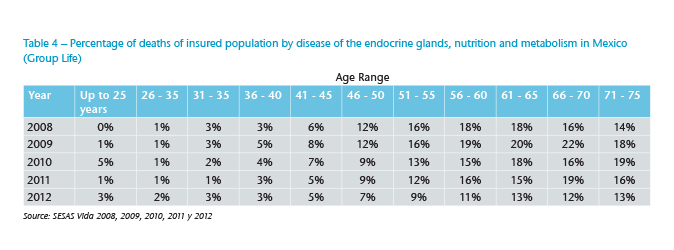

Despite the low penetration, the impact of deaths from endocrine, nutrition and metabolic disease is reflected in insurance claims in individual and group life portfolios (Figures 3 and 4). On average 15% of all deaths of people between 46 and 75 years of age are attributed to these causes. Although it is difficult to determine the exact number of deaths due to overweight and obesity, we can say that these conditions occupy a considerable percentage of this segment, given the impact diabetes mellitus has had on causes of death. It is, however, important to note that this category does not include those cases where the final cause of death was cancer or heart disease, which may have been caused by complications from overweight and obesity, so 15% could be an underestimate of the true rate.

Several studies conducted by insurance companies in the US show that disability rates for individuals aged 30 to 59 have increased by approximately 130% in recent years, across all demographic and economic groups, whereas diabetes and other musculoskeletal problems commonly associated with overweight and obesity constitute the major cause of increased disability rates in young people.17 However, the definitions often used by insurance companies to determine what constitutes a disability are based on a significant reduction in the insured’s ability to perform certain day-to-day activities, such as eating, bathing, dressing, moving about a room, etc. A study in the US revealed that being overweight reduces the ability of men to perform daily life tasks by 50%, while severe obesity reduces these skills by 300%. Results from the same study for women are even more alarming.18

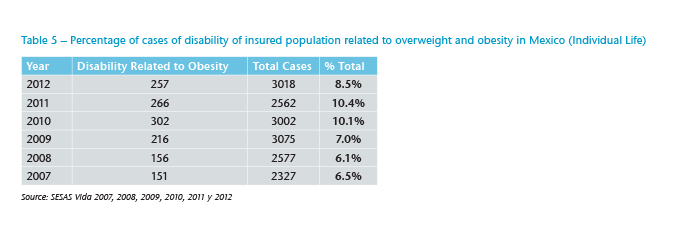

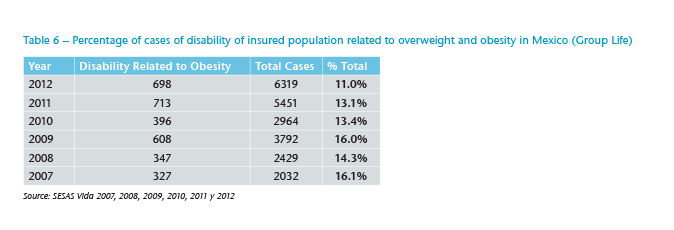

Should the trend observed in the prevalence rates of overweight and obesity continue, the number of disability claims could significantly increase. Tables 5 and 6 show the percentage of disability cases of insured lives associated with overweight and obesity. The percentages are similar to those for death claims; however, for group life portfolios, the negative trend in rates over time is significant. For individual portfolios, peaks are observed in the years 2010 and 2011, although the rate in 2012 is even higher than the levels observed prior to 2010.

There are some measures that insurance companies could take to control the accidental death and disability claim rates. For example, if an applicant is only marginally overweight – free of other risk factors such as diabetes, vascular disease or hypertension – then a rating could apply, in accordance to the provisions in the underwriting manual used by the company. An applicant with additional risk factors would require further evaluation to determine final terms.

To exclude obesity as a specific cause of death or disability claim, especially in the presence of additional risk factors such as diabetes, would be complex. It would also hinder claims management; the disease is chronic and degenerative, and awkward to define, making it difficult to determine whether death or disability is a direct cause of any related condition. This becomes more complicated in medical expenses insurance. Although surcharges may be appropriate for life and disability coverage, in health they do not solve the problem, especially when there are risk factors associated with obesity or overweight.

Providing health cover to individuals with chronic degenerative disease implies that any claims will be paid unconditionally and without limit. Although their life expectancy is determined to an extent by treatment, the medical expenses associated with providing that treatment are, in contrast, fixed. Obese people spend, on average, 36% more on health and 77% more on medication than non-obese people do.19

In Mexico, life and health insurers may still offer premiums differentiated by gender. There is a correlation between education level and overweight in females; those with little education are two to three times more likely to be overweight compared to those with a high level of education, while in men there is no significant difference.20

One reason for the low penetration of health insurance in Mexico is yearly premium increases that are especially high for people over age 60. The increases are attributed to the high levels of medical inflation coupled with a limited number of private hospitals and health services. Overweight and obesity increase the demand for health services, significantly impacting insurance costs.

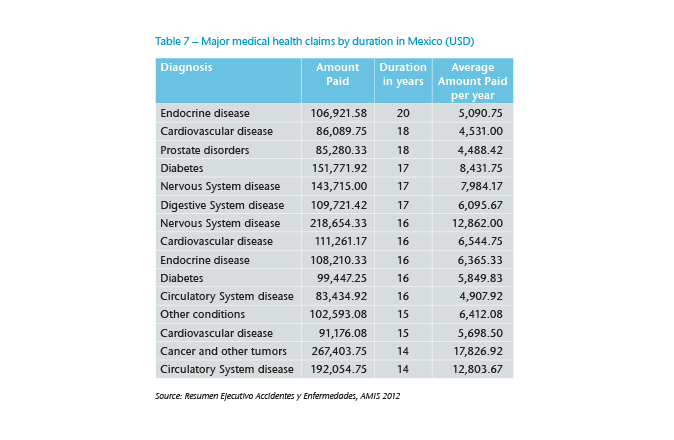

High BMI itself does not appear on the list of most expensive medical claims but diabetes is among the 20 most frequent diagnoses in health insurance claims and in the top 10 by duration (see Table 7).

In the short-term the challenge for health insurers from claims caused by high BMI is that they are frequent rather than large. Furthermore, the increase in the incidence of these diseases raises the already high premiums for major medical expenses coverage, which could also have a major effect on the lapse rate of these policies (especially after a certain age). This could tarnish the image of insurance as the perception of policyholders is that their cover becomes too costly as they get older. This could generate an adverse effect on the selection in the portfolio – especially if most lapses are “good risks” while unhealthy people continue their cover – making coverage of major medical expenses unsustainable over the long term.

Conclusion

Combatting obesity requires the implementation of a combined strategy by the government, at home, in school and by the media. Many governments, including that of Mexico, have taken action in an effort to control the prevalence rate in the population, especially in children. Taxes have been imposed on food and beverages with high caloric intake to discourage consumption of these products. Awareness campaigns have been conducted, nutrition advice offered and national obesity policies implemented.

The NHANES results show a slowdown in the upward trend in overweight and obesity prevalence in those children and adolescents in Mexico. The fact that no significant increase has been observed since 2006 is encouraging, as previous surveys showed high rates and ever-growing incidence at younger ages. The slowdown in the growth of overweight and obesity prevalence in children and adolescents in Mexico corresponds with that recently observed for various age groups in other countries. Policies and action plans to combat obesity could partly explain this effect; however, it is too early to make that judgement.

The prevalence of overweight and obesity remain unacceptably high. One saving grace may be that there is a percentage of the population with a high propensity to become overweight and obese for genetic reasons; thus, certain populations may have already reached the ceiling of this prevalence.21 Undoubtedly, preventive medicine is a crucial element in combating obesity, that and reducing the economic and social costs involved in treatment. For now, insurers should encourage a preventive culture and continue to monitor trends in the incidence of excess weight. Furthermore, underwriters must pay particular attention to this condition during the selection process if major claims deviations in their portfolios are to be avoided.