-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

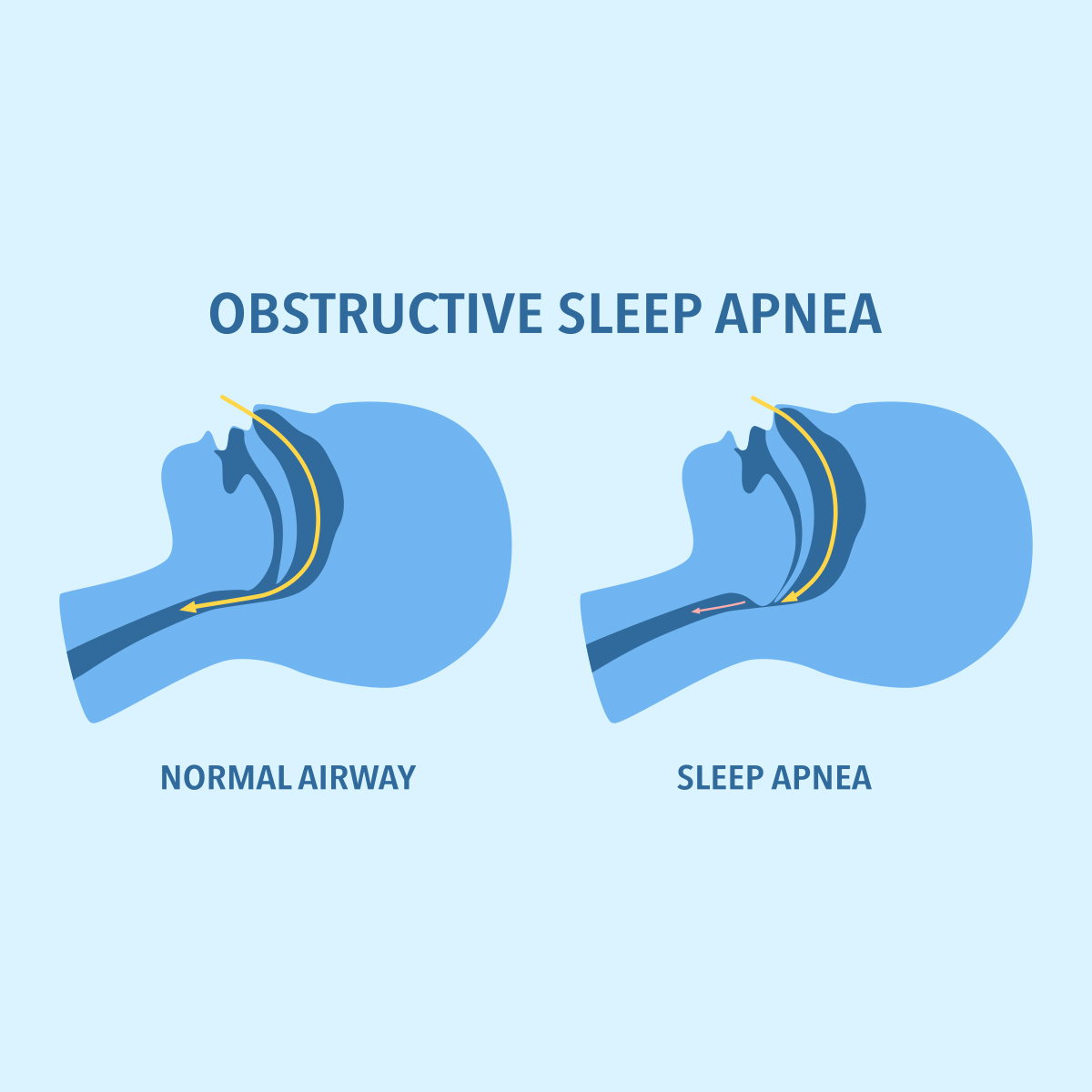

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Finding the Balance – Assessing Weight Changes in Underwriting

April 08, 2025

Elena Dorando,

Cheryl Agyei

English

Body mass index (BMI) is the measure most often used to identify unhealthy weight in clinical practice, as well as in insurance underwriting. The BMI is based on the weight and height of a person, calculated by the formula BMI = weight in kg/height in meters squared. While BMI is easy to determine and less prone to measurement errors than other measures of adiposity, it is often criticized because it cannot distinguish between lean and fat mass, and it cannot indicate how fat mass is distributed in the body. This is relevant because research has shown that fat accumulation at the waist increases cardiovascular risk more than body fat accumulations elsewhere in the body.

Perspectives on the Body Mass Index

Other studies have shown that on an aggregated population level BMI correlates well with fat and lean mass.1 It has also been shown that BMI has a good specificity of approximately 90% to 99%, i.e. the likelihood that a person with a high BMI also has a high proportion of adipose tissue is high.2,3

There are, however, specific populations for which BMI is not an accurate measure of adiposity. This includes athletes and bodybuilders with high muscle-to-fat ratio, where BMI might overestimate proportion of adipose tissue. Furthermore, the standard BMI formula is not applicable to people with amputations, pregnant women, and young children. Here, different approaches must be taken or adaptations to the BMI formula must be made. For example, studies investigating BMI in amputees have adjusted the BMI formula calculation to account for the missing limb(s) and the issue of altered body weight distribution, offering a more accurate assessment of body composition and its implication for health in this population.4

Another, very important, issue for risk prediction is the BMI’s limited sensitivity. According to studies, the sensitivity of BMI, i.e. the likelihood that a person with a normal BMI has a normal proportion of body fat, is relatively low, at approximately 36% to 50%.5,6 This means that looking only at the BMI of a person can underestimate the actual risk. This is the reason why using BMI in conjunction with other cardiovascular risk markers, such as blood pressure, blood lipids and blood sugar, is important to identify normal-weight people with an unhealthy metabolic risk profile.

An additional method to improve the BMI’s sensitivity and applicability is to use it in conjunction with other build measures such as waist circumference (WC), which directly considers central adiposity, a key indicator of metabolic health. Several studies have established that an increase in WC within each BMI category is positively associated with increased all-cause mortality, even after a further adjustment for BMI.7 A few studies have integrated BMI and WC into a single index, demonstrating an increased risk linked with an elevation in the combined index. One study allocated participants into WC decile and BMI decile groups. The deciles indicate where the individual participant is in relation to the overall study population in terms of their individual WC and BMI. Participants with a larger difference between WC decile and BMI decile showed increased mortality in the study, which remained after adjustment for BMI.8 Applicants with a normal or only slightly increased BMI and a relatively large WC therefore represent an increased risk.

In addition to WC, other build measures are regularly examined for their usefulness. These include, for example, the waist-to-hip ratio and the waist-to-height ratio. A major limitation of these body measurements, in addition to the generally more limited data available, is their susceptibility to measurement errors and their rare availability in underwriting. In addition, the threshold above which an increased health risk is to be expected is less standardized for those measures.

All in all, BMI is a valuable marker for underwriting as it correlates well with cardiovascular risk on a population level and is easily available. Other weight and build measures are more prone to measurement errors and there is less reliable evidence available on how significantly they correlate with cardiovascular risk. However, it can make sense to use certain measures, such as WC, in combination with BMI to improve the sensitivity of BMI on an individual level.

What is a “Normal” Weight?

Another important question that arises when discussing weight and build is what can be considered a standard risk. In underwriting, product pricing plays an essential role for defining what is considered a “normal” weight and thus what loading is appropriate. It should be noted that for conditions with a high population prevalence, such as overweight, often a part of the risk is already priced in the base premium. If, and what range of, risk is priced in depends on the specific product. Thus, pricing a part of the risk in the base premium can widen the range of BMI values that are accepted as standard risk in underwriting. However, this does not necessarily imply that the priced‑in BMI range is the medically optimal range.

The World Health Organization defines normal weight as a BMI of 18.5 to 24.9. In the past, it has been discussed repeatedly whether this “normal” weight range is also the optimal, most healthy weight. Some studies are suggesting that overweight (BMI ≥25 to 29.9) could be protective compared to normal weight (BMI 18.5 to 24.9). However, when looking at analyses of different age categories, this effect of “healthy overweight” is limited to older age groups (≥65 years in Visaria et al.9).

This suggests that the mechanism which makes overweight appear to be preferable to normal weight is the high prevalence of underlying chronic conditions and/or frailty with loss of muscle mass in older age groups, which results in unintended weight loss and thus appears as a normal BMI in previously overweight people.

This implies two important learnings for the underwriting perspective:

- BMI assessments should be age dependent. The older the applicant, the more the optimal BMI range shifts towards higher BMIs.

- Comorbidities and unintentional weight loss should be assessed carefully, even if the current BMI appears to be normal and would not be ratable based on the BMI value alone.

Impact of Weight Change on Underwriting

With the emergence of potent weight loss medications, including GLP‑1 receptor agonists such as semaglutide, applicants with a history of significant weight change are likely to be seen more often in underwriting. In general, significant weight changes must not always be intentional but can also result from underlying conditions that may or may not yet be diagnosed.

Therefore, the first question that should be asked in underwriting when seeing significant weight loss is:

Was the weight loss intentional or unintentional?

Unintentional weight loss can be an important sign of various severe underlying conditions which could cause an early claim if missed at underwriting stage. These conditions include among others: cancers; infectious diseases (e.g. HIV, tuberculosis, hepatitis C); endocrine disorders (e.g. hyperthyroidism, uncontrolled diabetes type 1); gastrointestinal disease (e.g. gastric ulcers, coeliac disease, irritable bowel syndrome); and advanced chronic diseases (e.g. congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, advanced kidney disease). If there is unexplained and significant weight loss, insurance cover for any benefit type should not be granted until the reason for weight loss has been fully investigated.

Intentional weight loss can be achieved through lifestyle modifications (e.g. dietary changes, increased physical activity); weight loss medications; bariatric surgery; or a combination thereof. To assess intentional weight loss in underwriting, one must consider positive health effects on one hand but also the risk of long-term side-effects and sequelae of the weight loss method on the other hand.

Thus, another question that is helpful for underwriting is:

If weight loss was intentional, what method was used to achieve it?

Benefits and Harms of Different Weight Loss Methods

Overweight-related comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, sleep apnoea, and chronic kidney disease significantly contribute to the morbidity burden and metabolic risk associated with obesity. To address this issue, various methods for weight reduction have been developed. These methods not only focus on reducing weight but also aim to reduce the burden of these comorbidities.

A large database study from the UK investigated the impact of recent, intentional weight loss on overweight-related comorbidities compared to a population with a stable normal weight. The study aggregated data for different intentional weight loss interventions (57.6% on weight loss diet, 27% on weight loss medication, 1.1% with bariatric surgery) and had a median follow‑up of 6.3 years. The analysis illustrates that the risk for diabetes, sleep apnoea, chronic kidney disease, hypertension and dyslipidaemia significantly decreases, almost to the level of people with a stable normal weight. However, risk of heart failure and atrial fibrillation remained high even after weight loss.10

A significant improvement of cardiovascular biomarkers, reduced time-to-first fatal or nonfatal cardiovascular event and reduced all-cause mortality has also been observed specifically for the GLP‑1 receptor agonists-based weight loss medication semaglutide.11

On the other hand, there have been several case reports of serious adverse events in people taking weight loss medication. These included, for example, cases of gastroparesis and pancreatitis, but also reports of self-harm and suicidal thoughts. However, GLP‑1 R analogues have shown no causal relationship with these severe adverse events in studies with an adequate control group or sufficient adjustment for confounders.12,13 Mild gastrointestinal side-effects are more common, but they have limited relevance to risk prediction in underwriting. Given the currently available evidence, GLP‑1 analogues can be categorized as having a risk of harms that is comparable to other approved medications that are usually not explicitly addressed in underwriting.

Therefore, we do not recommend applying additional safety-loadings for GLP‑1 R analogues out of concern for serious side-effects. Intentional weight loss with any weight loss medication can be assessed similarly to significant weight loss achieved by lifestyle changes.

What Changes With Effective Weight Loss Medications?

There is, however, something else that needs special consideration when looking at the impact of these highly effective weight loss medications on underwriting weight and build: the proportion of applicants with a significant weight change history will become much higher with widespread availability of semaglutide, tirzepatide, and other effective medications. We do also know that weight reduction and improvement of cardiovascular risk markers can probably be maintained in the long term only if medication is continued.14,15

Based on the currently available data, it is difficult to predict which applicants will successfully continue to be on the medication and maintain their weight, and which not. Adherence rates have been different for diabetic and non-diabetic populations and for different agents (e.g. semaglutide, dulaglutide, or liraglutide).16 However, the following factors have been shown to correlate with stopping GLP‑1 R based medications: financial burden for the individual, availability of the medication, individually experienced side-effects, and effectiveness of medication on weight loss.17

The challenge faced by underwriters and pricing actuaries is that the currently available data used for BMI ratings does not yet include the impact of widely accessible and highly effective weight loss medications. There is a natural time lag in the data, so studies with long-term data including the “new normal” proportion of people with recent, significant weight loss (and increased risk of future significant weight gain) need first to be performed and analysed before we know the exact impact of these medications on future BMI‑changes.

All in all, we suspect that with widely accessible and effective weight loss medications, there is a higher risk of more insured individuals changing their BMI after underwriting, e.g. if medication is stopped for any reason. It is likely that this risk is not currently included in the calculations for pricing and loadings from the available data.

To account for this discrepancy, we recommend underwriters to ask:

What was the extent of the weight loss and how rapid was it?

If significant (defined as >5% of original body weight) and recent (defined as within the last 12 months) intended weight loss is seen in an applicant, the future elevated risk of weight regain should be accounted for. For these cases, we recommend using the average of the weight at application and the weight before start of the significant weight loss to calculate an average BMI that is used to look up the respective rating in the underwriting manual.

Example:

- Weight 12 months ago: 100kg

- Current weight: 90kg

Average weight that is used to calculate the BMI that is then rated:

(100kg + 90kg): 2 = 95 kg

With this rule, half of the recently achieved weight loss is accounted for in underwriting. It simultaneously considers the positive effects of weight loss on cardiovascular and general health and the increased risk of future weight change. The rule can also be applied for recent, significant weight change achieved by lifestyle changes and bariatric surgery. However, for bariatric surgery, short- and long-term side-effects and sequelae of the surgery must be considered additionally.

An Update on Underwriting Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric surgery remains one of the most effective treatments for severe obesity, and in most cases, it leads to significant and sustained weight loss. Clinical indications for bariatric surgery are a BMI above 40, or between 35 and 40 plus comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, or obstructive sleep apnoea.

Beyond weight reduction, bariatric surgery often leads to the remission of obesity-related conditions, contributing to improved long-term health outcomes. Several studies have demonstrated a reduction in all-cause mortality and obesity-associated cancer risk after bariatric surgery.18

From an underwriting perspective, the type of bariatric surgery procedure and the duration since the procedure are key factors in assessing risk. While the procedure has been proved to offer substantial benefits in weight loss, it also brings the risk of serious long-term complications including nutritional deficiencies such as osteoporosis and anaemia, dumping syndrome, and even bariatric revision surgery.

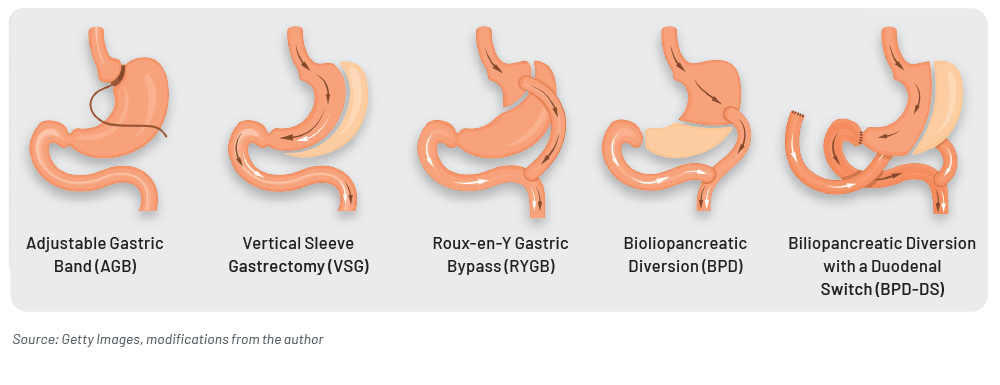

Currently, the most performed bariatric procedures are the sleeve gastrectomy (SG), a type of “restrictive” procedure which limits the amount of food the stomach can hold, thereby reducing calorie intake; and the Roux‑en‑Y gastric bypass (RYGB), a “combined” procedure, which incorporates both restrictive and malabsorptive elements, limiting calorie intake as well as reducing nutrient absorption. Both procedures have been well documented to produce significant results in terms of weight loss efficacy and reduced overall mortality rates in individuals with obesity. For example, the SLEEVEPASS study reported a 57% excess weight loss in patients who had undergone an RYGB procedure compared to 49% excess weight loss in patients who had undergone the SG procedure after a five-year follow‑up.19

Studies have shown that weight regain, as well as the incidence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) may be more common in restrictive surgeries such as SG, leading to a higher rate of revisional surgery. On the other hand, while the longer-term effectiveness may be higher in RYGB-type surgeries in terms of excess weight lost, there appears to be a higher risk of long-term complication, requiring lifelong supplementation.20

The rate of weight loss is highest during the first-year post-procedure, with some studies demonstrating a peak at two years and then stabilising. A stable weight for at least one-year post-surgery is a positive indicator, suggesting a lower risk profile for underwriters. When underwriting individuals with a history of bariatric surgery, it is essential to consider the long-term effectiveness of the procedure, the weight loss efficacy, the progression of comorbidities, and the use of adjunctive therapies to inform the risk assessment.

Weight loss medications are an emerging trend in obesity management, also in combination with bariatric surgery. While these medications show good results for weight loss, their impact on long-term outcomes is not yet fully understood. Studies have emerged showing the use of these medications in mitigating weight regain after bariatric surgery.21 In the coming years, it is anticipated that there will be a significant increase in the number of long-term, and larger scale studies assessing the effectiveness of weight loss medications in combination with different bariatric surgery procedures, which will provide more robust data on how these medications influence weight loss.

Additionally, there may be new considerations around the timing of surgery and the specific use of medications as a pre- or post-surgical strategy. Future updates to guidelines will need to account for the potential of these medications to enhance or alter the risk profiles associated with weight loss and bariatric surgery.

Conclusion

New weight loss methods, such as GLP‑1 analogues and improved bariatric surgery techniques, have the potential to change the proportion of severely overweight individuals in the general population. Although the long-term effects of new weight loss methods are not yet fully understood, current evidence suggests a promising potential to reduce obesity-associated morbidity and mortality. This development requires special attention to underwriting, especially regarding an applicant’s weight history. In particular, a distinction must be made between intentional and unintentional weight loss. Additionally, in the case of intentional, significant weight loss, the elevated risk of future weight regain must be adequately considered.

- Flegal, K. M., Shepherd, J. A., Looker, A. C., Graubard, B. I., Borrud, L. G., Ogden, C. L., Harris, T. B., Everhart, J. E., & Schenker, N. (2009). Comparisons of percentage body fat, body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-stature ratio in adults. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 89 (2), 500–508.

- Romero-Corral, A., Somers, V. K., Sierra-Johnson, J., Thomas, R. J., Collazo-Clavell, M. L., Korinek, J., Allison, T. G., Batsis, J. A., Sert-Kuniyoshi, F. H., & Lopez-Jimenez, F. (2008). Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. International journal of obesity (2005), 32 (6), 959–966.

- Okorodudu, D. O., Jumean, M. F., Montori, V. M., Romero-Corral, A., Somers, V. K., Erwin, P. J., & Lopez-Jimenez, F. (2010). Diagnostic performance of body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body adiposity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of obesity (2005), 34 (5), 791–799.

- Mozumdar, A., & Roy, S. K. (2004). Method for estimating body weight in persons with lower-limb amputation and its implication for their nutritional assessment. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 80 (4), 868–875.

- Romero-Corral, A., Somers, V. K., Sierra-Johnson, J., Thomas, R. J., Collazo-Clavell, M. L., Korinek, J., Allison, T. G., Batsis, J. A., Sert-Kuniyoshi, F. H., & Lopez-Jimenez, F. (2008). Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. International journal of obesity (2005), 32 (6), 959–966.

- Okorodudu, D. O., Jumean, M. F., Montori, V. M., Romero-Corral, A., Somers, V. K., Erwin, P. J., & Lopez-Jimenez, F. (2010). Diagnostic performance of body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body adiposity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of obesity (2005), 34 (5), 791–799.

- Cerhan, J. R., Moore, S. C., Jacobs, E. J., Kitahara, C. M., Rosenberg, P. S., Adami, H. O., Ebbert, J. O., English, D. R., Gapstur, S. M., Giles, G. G., Horn-Ross, P. L., Park, Y., Patel, A. V., Robien, K., Weiderpass, E., Willett, W. C., Wolk, A., Zeleniuch-Jacquotte, A., Hartge, P., Bernstein, L., Berrington de Gonzalez, A. (2014). A pooled analysis of waist circumference and mortality in 650,000 adults. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 89 (3), 335–345.

- Reges, O., Test, T., Dicker, D., & Karpati, T. (2024). Association of Waist Circumference and Body Mass Index Deciles Ratio with All-Cause Mortality: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrients, 16 (7), 961.

- Visaria, A., & Setoguchi, S. (2023). Body-Mass-Index und Gesamtmortalität in einer US‑Bevölkerung des 21. Jahrhunderts: A National Health Interview Survey analysis. PloS one, 18 (7), e0287218.

- Haase, C. L., Lopes, S., Olsen, A. H., Satylganova, A., Schnecke, V., & McEwan, P. (2021). Gewichtsabnahme und Risikoreduktion von fettleibigkeitsbedingten Folgen bei 0,5 Millionen Menschen: Erkenntnisse aus einer britischen Primärversorgungsdatenbank. International journal of obesity (2005), 45 (6), 1249–1258.

- Lincoff, A. M., Brown-Frandsen, K., Colhoun, H. M., Deanfield, J., Emerson, S. S., Esbjerg, S., Hardt-Lindberg, S., Hovingh, G. K., Kahn, S. E., Kushner, R. F., Lingvay, I., Oral, T. K., Michelsen, M. M., Plutzky, J., Tornøe, C. W., Ryan, D. H., & SELECT Trial Investigators (2023). Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. The New England journal of medicine, 389 (24), 2221–2232.

- Lincoff, A. M., Brown-Frandsen, K., Colhoun, H. M., Deanfield, J., Emerson, S. S., Esbjerg, S., Hardt-Lindberg, S., Hovingh, G. K., Kahn, S. E., Kushner, R. F., Lingvay, I., Oral, T. K., Michelsen, M. M., Plutzky, J., Tornøe, C. W., Ryan, D. H., & SELECT Trial Investigators (2023). Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. The New England journal of medicine, 389 (24), 2221–2232.

- European Medicines Agency (2024). Meeting highlights from the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) 8‑11 April 2024, www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/meeting-highlights-pharmacovigilance-risk-assessment-committee-prac-8-11-april-2024 (abgerufen am 15.04.2024).

- Rubino et al. & STEP 4 Investigators (2021). Effect of Continued Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo on Weight Loss Maintenance in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 325(14), 1414–1425. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.3224.

- Aronne, L. J., Sattar, N., Horn, D. B., Bays, H. E., Wharton, S., Lin, W. Y., Ahmad, N. N., Zhang, S., Liao, R., Bunck, M. C., Jouravskaya, I., Murphy, M. A., & SURMOUNT‑4 Investigators (2024). Continued Treatment With Tirzepatide for Maintenance of Weight Reduction in Adults With Obesity: The SURMOUNT‑4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 331(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.24945.

- Uzoigwe, C., Liang, Y., Whitmire, S., & Paprocki, Y. (2021). Semaglutide Once-Weekly Persistence and Adherence Versus Other GLP‑1 RAs in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in a US Real-World Setting. Diabetes therapy: research, treatment and education of diabetes and related disorders, 12 (5), 1475–1489.

- Ko, H. J., Kim, J. W., & Lim, S. (2022). Adherence to and Dropout from Liraglutide 3.0 mg Obesity Treatment in a Real-World Setting. Journal of obesity & metabolic syndrome, 31 (3), 254–262.

- Aminian, A., Wilson, R., Al‑Kurd, A., Tu, C., Milinovich, A., Kroh, M., Rosenthal, R. J., Brethauer, S. A., Schauer, P. R., Kattan, M. W., Brown, J. C., Berger, N. A., Abraham, J., & Nissen, S. E. (2022). Association of Bariatric Surgery With Cancer Risk and Mortality in Adults With Obesity. JAMA, 327 (24), 2423–2433.

- Salminen, P., Grönroos, S., Helmiö, M., Hurme, S., Juuti, A., Juusela, R., Peromaa-Haavisto, P., Leivonen, M., Nuutila, P., & Ovaska, J. (2022). Auswirkungen der laparoskopischen Sleeve-Gastrektomie im Vergleich zum Roux‑en‑Y-Magenbypass auf Gewichtsverlust, Komorbiditäten und Reflux nach 10 Jahren bei erwachsenen Patienten mit Adipositas: Die randomisierte klinische Studie SLEEVEPASS. JAMA Chirurgie, 157 (8), 656–666.

- Gu, L., Huang, X., Li, S., Mao, D., Shen, Z., Khadaroo, P. A., Ng, D. M., & Chen, P. (2020). A meta-analysis of the medium- and long-term effects of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Roux‑en‑Y gastric bypass. BMC surgery, 20 (1), 30.

- Istfan, N. W., Anderson, W. A., Hess, D. T., Yu, L., Carmine, B., & Apovian, C. M. (2020). The Mitigating Effect of Phentermine and Topiramate on Weight Regain After Roux‑en‑Y Gastric Bypass Surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 28 (6), 1023–1030.