-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

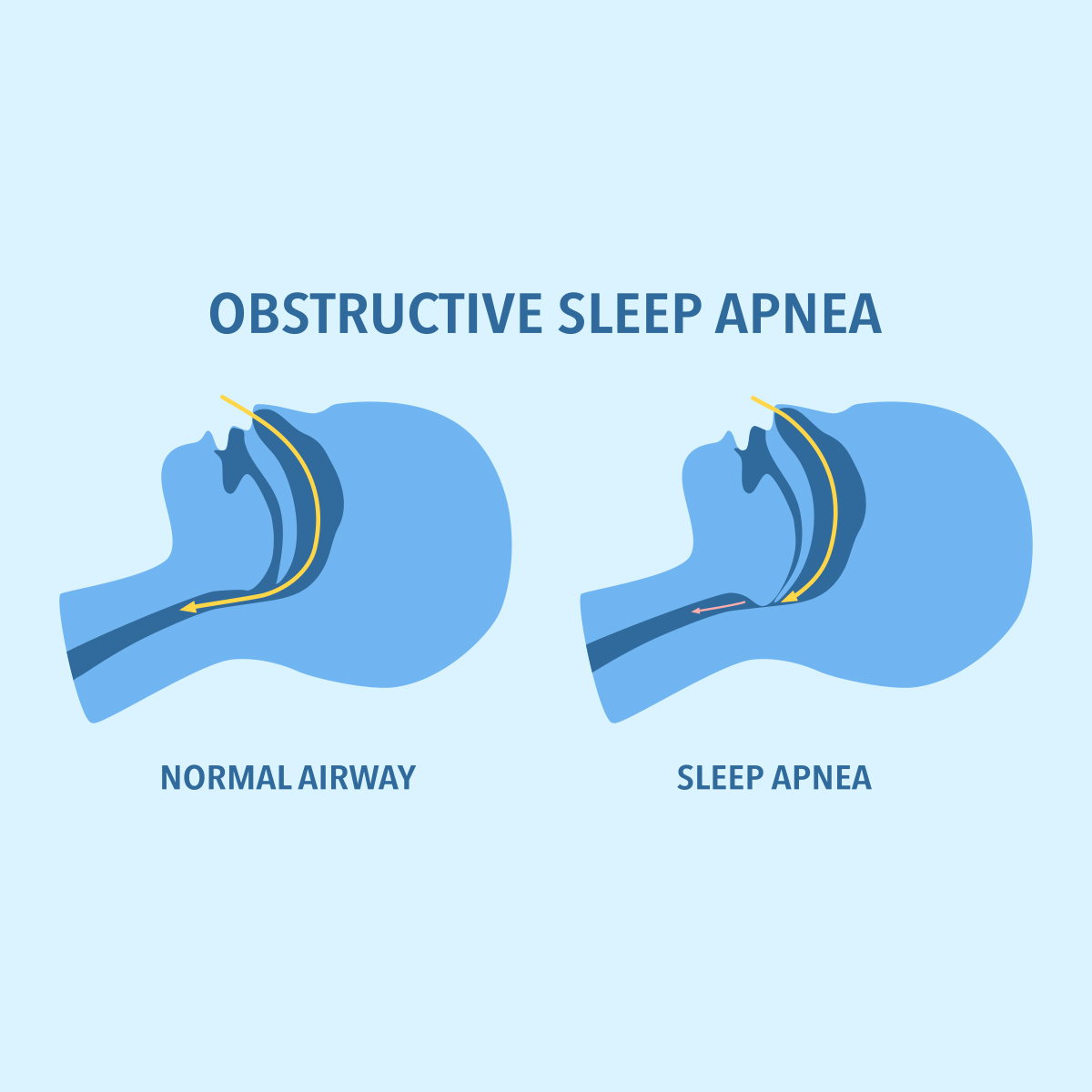

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

The “Epidemic” of Mental Disorders - Rhetoric and Reality

December 12, 2020

Dr. Chris Ball

English

Français

Mental health has become a big topic of discussion in the media. Headlines describing mental health problems at epidemic levels are common - and many come from “research” cited by insurers. We know antidepressant prescription rates have doubled in high income countries over the millennium, to the extent that over 10% of the population in the U. S. and Australia take these drugs. So, is there really an epidemic of mental illness?

Toshi Furukawa, Professor of Clinical Epidemiology at the University of Kyoto, upbraided popular writers for “touting such sensational words like ‘epidemic’, ‘plague’ or ‘pandemic’”.1 A systematic review by Richter et al. concluded that the prevalence increase in adult mental illness is actually small and that it was mainly related to demographic changes.2 This is a view supported by Harvey Whiteford, Professor of Population Mental Health at the University of Queensland, who was quoted as saying, “There is no epidemic of mental illness sweeping the world…survey data which has tracked over time shows that the prevalence hasn’t changed - it’s flatlined.”3

DSM-5, the diagnostic manual from the American Psychiatric Association, states, “People are negatively affected by the continued and continuous medicalisation of natural and normal responses to their experiences; responses which have distressing consequences but do not reflect illnesses so much as normal individual variation”. This creates difficulties for the insurance industry, because it largely relies on a medical model to support its products, particularly in Disability Income (DI).

When an episode of psychological distress is disclosed by an insurance applicant, finding the right label for it is always an early step in the assessment process. At one level, a simple solution for the underwriter could be to continue with the medical model and rate for a diagnosis or any small indication of a diagnosis, lumping all psychological distress together.

However, the outcomes of these disorders are strongly influenced by studies that mostly follow small samples of patients who encountered secondary care services because of the severity of their illness. These groups are rarely representative of the overall population, not adjusted for physical disorders, followed up for relatively short times and subject to publication bias. Including only these patients substantially over-estimates both all-cause mortality and suicide risk.

Clearly, this approach to risk assessment appears unfair to people who have experienced episodes of psychological distress but whose risk is low or the same as the general population. The situation is rather different in DI where mental health claims are common and perceived as prolonged and difficult to manage. Where psychological distress is disclosed by the DI applicant, a purely diagnostic approach proves a weak discriminator of risk. Exclusions are not well understood by consumers nor easy to enforce at claim stage.

The management of any episode of psychological distress in clinical practice is not just a matter of diagnosis but requires understanding in a much broader context. The individual’s experiences are important, but the history, personality, resources, social setting and the nature of the circumstances themselves must be grasped. Using this bio-psycho-social model helps to understand why one person experiences significant distress (possibly illness) in a set of circumstances, whilst another manages perfectly well.

Identifying the main aspects of an individual and his or her circumstances could provide the key to clarifying risk and mitigating its impact. For some, where the risk is likely to be long-term and specific, then an exclusion may be helpful, or a rating may be more appropriate. In other cases, where a singular set of circumstances led to distress, a blanket exclusion could be unreasonable. Developing an underwriting matrix that starts by identifying where the person is within the bio-psycho-social space is not beyond the bounds of possibility, particularly with technology to help this process. It need not fly in the face of trends in quick access and instant quotes, once systems are up and running.

People today are encouraged to engage with helping agencies to ameliorate the most ordinary levels of psychological distress. In turn, the insurance industry needs to ensure that people have access to the protection it can provide, with the expectation that their claims will be assessed consistently and fairly.

Endnotes

- Furukawa, T.A. (2019). An epidemic or a plague of common mental disorders? Acta Psychiatrica Scaninavica, 140(5), 391-392. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/acps.13108 (accessed 19 May 2020).

- Richter et al., (2019) Is the global prevalence rate of adult mental illness increasing? Systematic review and meta‐analysis, Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Volume 140(5), 393-407. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13083.

- https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/jun/08/prevention-the-new-holy-grail-of-treating-mental-illness (accessed 19 May 2020);

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/jun/03/mental-illness-is-there-really-a-global-epidemic (accessed 19 May 2020).