-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Biometric Information Privacy – Statutes, Claims and Litigation [Update]

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves?

Publication

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Illinois Changes Stance on Construction Defect Claims – The Trend Continues

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Four Aspects of the Current Debate

Publication

Battered Umbrella – A Market in Urgent Need of Fixing -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Underwriting High Net Worth Foreign Nationals – Considerations for U.S. Life Insurance Companies

Publication

Group Term Life Rate & Risk Management – Results of 2023 U.S. Survey

Publication

Trend Spotting on the Accelerated Underwriting Journey

Publication

All in a Day’s Work – The Impact of Non-Medical Factors in Disability Claims U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

Marginal Gains in the Medicare Supplement Market -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Straight From the Heart – Can Insurers Help Prevent Cardiovascular Events?

September 26, 2019

Tim Eppert,

Sarah Hogekamp

English

Español

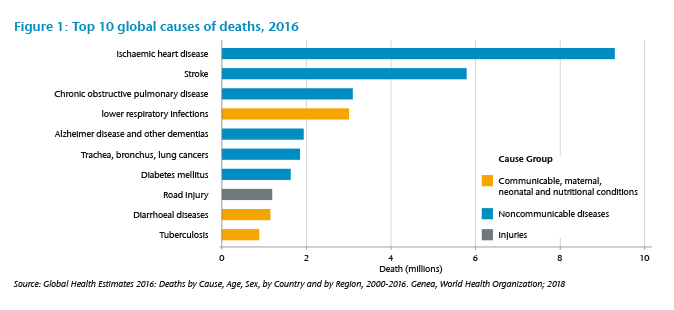

It is well known that cardiovascular diseases, such as heart attacks, are the leading cause of death worldwide. As well as being life-threatening they are also often a warning sign to individuals that can lead to lifestyle changes. It is understandable that the insured, who was diagnosed with a heart attack, expects his Critical Illness (CI) cover to pay a benefit. This, however, might not always be the case, depending on the severity level and the CI definitions.

This expectation has, in some markets, created pressure for insurers to offer CI products based on diagnosis-only definitions. In this case, a benefit is paid for every heart attack diagnosed by a medical professional, irrespective of the severity of the event. But paying each claim resulting from a heart attack is not always in the best interest of all insureds because claims payments that exceed the insurable interest lead to higher than necessary premiums.

We have seen enormous medical progress in the field of cardiovascular disease over the past decades. Treatment of heart attacks has improved to the point where they often cause less harm than they would have done 30 years ago. The Swedish Heart Failure Registry, which conducts detailed analyses of heart attack incidence and mortality annually, found that 365-day mortality after a heart attack has dropped from almost 20% in 1995 to less than 10% for the years 2007 onwards.2

This reduction reflects not only improved treatments but also changes in the detection of heart attacks. With biomarker tests, namely troponin, and more recently high-sensitive troponin, heart attacks can be detected earlier and more accurately than before, resulting in earlier and more precise treatment. Before the introduction of troponin, some heart attacks that did not cause ECG changes or showed unclear changes (NSTEMI) were classified as Angina Pectoris (chest pain).3 Since then, the proportion of full thickness infarctions of the heart (so called STEMI), which are predominantly defined by ECG changes and less by raised troponin levels, has dropped significantly over the past years. The increasing number of diagnosed NSTEMI’s are mainly responsible for this reduction. A higher proportion of – on average – less severe NSTEMI infarctions, better diagnostics and therefore more precise and faster treatment have all contributed to the observed reduction in heart attack mortality. There are now many cases where the pumping function of the heart – the ejection fraction (EF) – is not significantly reduced after a heart attack.

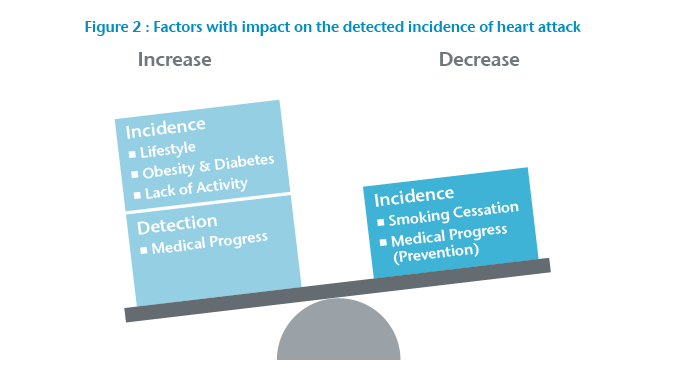

Within the same period, the incidence rate was also observed as stagnating or declining in many countries.4 A major cause of this reduction is likely to be the decline in smokers in these countries. But, the potential gains from smoking cessation are not endless and, in several countries, we see that progress is slowing. Negative effects of the modern lifestyle, with its oversupply of calories and lack of physical activity, weigh heavily against the positive effects from smoking cessation (Figure 2).

“Heart attacks have been and still are a major health threat”

Between 1980 and 2015 the prevalence of obesity more than doubled on a global scale, affecting both developed and developing countries.5 As a result, we observe a pandemic of obesity, hypertension and diabetes posing a major threat to cardiovascular health.

In summary, heart attacks have been and still are a major health threat. The demand for diagnosis-only benefits is understandable, but insuring every claim comes with a high risk of future changes. Outcomes continue to improve, which means that the negative impact on the quality of life after a heart attack will decrease and therefore the necessity for an insurance cover of a heart attack with a very good outcome becomes questionable.

What can be done?

Finding a common denominator between customer expectations and needs is crucial. What does the customer need the product for? In some markets CI cover is used as an add-on for health insurance. In this case, the policy needs to cover all acute heart attacks to provide a reimbursement-like benefit. But even though there is customer demand for the expensive pay-all-diagnoses approach, it is still a risky venture for the insurer, especially with guaranteed business. Here, stepped benefits can help to limit costs for minor events.

In markets where CI is used to cover debt and the long-term lack of income after a severe infarction, a more robust definition can be in the interest of the policyholder as it leads to more affordable rates.

The general product setting is also important. Is it a product with long durations and guaranteed rates? Then the risk of change and its impact on different severity levels in the definitions must be considered. We have the risk of increasing incidence rates due to lifestyle, which affects any definition. There is also a trend toward improved detection of heart attacks, which can lead to more claims for weak definitions only. A further shift to less severe heart attacks could improve outcomes for stricter definitions but would not change the experience for weak definitions. For these reasons, stricter definitions can be preferable for products with long term guarantees.

For a market operating under standard definitions set by the regulator, the potential to change the disease wording itself is limited and the insurer may be required to offer definitions with low to no severity levels. To limit the exposure to certain risk factors, other product features, such as the maximum sum insured or the duration of the contract, can be reduced.

Generally, the insurer should always look for outdated or unclear elements. The best way to ensure that the customer’s expectations match the insurance cover is to have transparent and easy to understand definitions with clearly stated severity requirements for the benefit payment. Ideally, the definitions should be reviewed regularly to depict the changes in medical definitions and treatment standards.

What are possible thresholds?

In some markets, we observe definitions where only STEMI infarctions are covered. This is a clearly defined severity level, but as the proportion of STEMI on all infarctions has decreased significantly in many markets, this may be considered as too restrictive. Also, while STEMI has a significantly higher 30-day-mortality than NSTEMI,6 the long-term effects are similar.7 While STEMI infarctions theoretically pose a transparent severity criterion, the similarity in long-term mortality and symptoms may still result in the customer feeling unfairly treated if he suffers from a severe NSTEMI.

Some definitions use troponin thresholds. These allow, from a medical point of view, for much more detailed differentiation between heart attacks. However, most laymen have hardly ever heard of troponin, let alone understand the implication of different troponin thresholds, so the transparency of such a definition is questionable. The upside of these thresholds are the clear criterion for medical professionals, the downside is the necessity for explanation by a medical professional for policyholders to understand the cover.

Additionally, the time that passes between the heart attack occuring and the measurement of the troponin level will impact the magnitude of the troponin substantially, which makes it even more difficult to use a fixed troponin value as a clear cut off point for a decision about a claim. In the past it was more common to measure serial troponin, which gave a detailed picture of the magnitude of the peak. Nowadays serial troponin is not routinely measured, meaning we only observe an excerpt of the curve, which may or may not be the peak. Hence, good policy wording includes changes in troponin, etc. but does not exclusively use a fixed troponin threshold.

It can be difficult for a claims department to decide whether or not the policyholder has a justified claim for a heart attack. Neither clinical symptoms, nor ECG changes, nor troponin alone can determine a heart attack with certainty. Even if the combination of all three indicates a heart attack, there are still cases where differential diagnoses must be excluded.8 We therefore suggest that to be understood clearly, a definition should differentiate between the attack itself and its sequelae. Wall motion abnormalities or a reduced ejection fraction can be good criteria to differentiate between minor and major heart attacks. Focusing on the long-term outcome of a disease makes it easier to explain why some events are covered and others are not. Policyholders can understand that a permanent and significant loss of heart function requires more financial protection than a minor infarction that allows the policyholder to go on with life as before the event.

“Differentiation between minor and major heart attacks is important”

If the definition contains limitations, it is important that these are communicated transparently and are not hidden in the small print. Only then will the consumer be able to make an educated decision and have the awareness that not every event is covered. This will reduce the number of unjustified claim requests and also the reputational risk for the insurer.

A different picture for surgeries

Heart surgeries, such as coronary artery bypass grafts or heart valve repairs, are often included in CI covers and they, too, are affected by medical progress.

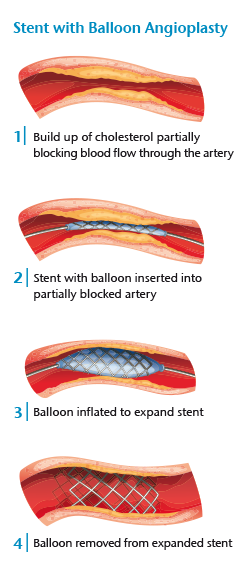

Many CI definitions require open-chest surgery as a benefit trigger, but nowadays this treatment is not always the best option from a medical point of view, given alternatives such as minimally invasive surgeries, and “non-surgical” procedures such as the insertion of stents. When reviewing the cover of surgeries in a CI context, questions the insurer can ask are:

- Is the treatment still a critical intervention that is comparable to other CI’s and how will it impact the quality of the insured’s life?

- Is there a major risk of increasing surgeries in the future if new techniques are accepted?

Many conditions that used to be treated by open-chest surgery, could technically be declined for coverage today when treated differently. As the severity of the underlying condition has not changed, it can be argued by the policyholder that this is overly strict. Minimally invasive surgery is used when the insured’s health is not fit to sustain open-chest surgery and vice versa. That does not mean that minimally invasive surgery is the generally preferred option, rather that treatment is based on many individual factors. For example, the duration of minimally invasive surgery is often longer than that of open-chest surgery, resulting in more time under anaesthesia, which is not an option for everyone. It can then be better to use open-chest surgery even though that brings other risks through higher blood loss and longer recovery periods. The underlying condition leading to minimally invasive surgery can be better, similar, or even worse than that leading to open-chest surgery. Therefore, it can be argued that CI insurance that covers open-chest surgery should also cover minimally invasive surgery.

Procedure vs. Surgery

The term “procedure” describes any method for performing a task.

A “surgery” is a procedure involving major incisions to remove, repair, or replace a part of a body. So, every surgery is a procedure, but not every procedure is a surgery. For example, the insertion of stents or balloon angioplasties neither remove, repair nor replace a part of a body but rather insert something to assist the weakened part. They are therefore procedures, but they are not surgeries.

Minimally invasive surgeries, as the name implies, fulfill the condition to be a surgery because they are used to remove, repair or replace part of a body.

Non-surgical procedures, such as the insertion of stents, present a different picture. They are increasingly used in lower levels of cardiovascular disease and do not display typical CI features, such as long-term effects or high risks. Such a procedure can be a precautionary measure while the insured is still in decent health, but it neither displays a comparable risk to the surgeries that are covered in a CI policy, nor does it generally require long recovery periods. For example, a bypass graft has a recovery period of approximately 12 weeks with extensive rehabilitation training,9 whereas after the insertion of a stent, the patient can leave the hospital usually within 24 hours.10 For these reasons we would advise offering only partial benefits – if any – for non-surgical procedures in a CI product.

Preventing cardiovascular events

The best heart attack is the one that does not happen, and by now insurers have many chances to play a part in prevention. As discussed in the first section of this article, we are aware of many risk factors – obesity, diabetes, lack of physical activity and smoking – that have a negative impact on the insured’s cardiovascular health.

An increasing number of products incorporate prevention or lifestyle elements; for instance, measuring step count or other physical activity, or even incentivizing or nudging the policyholder toward a healthier lifestyle. As of now no comprehensive studies quantify the effect of increases in physical activity on improving the insured’s health status. Still, from what is available, it is safe to assume that incentives for a better lifestyle will have a positive effect on health. Plus, healthy people with a high level of physical activity may be more inclined to buy a product with lifestyle incentives – this might also reduce the number of claims in the portfolio.

“Insurers have chances to play their part in prevention”

Some CI policies also offer small benefits for the diagnosis of diabetes. Such a benefit can be useful for the insurer, as an earlier diagnosis leads to early treatment, which is important for avoiding or at least delaying secondary diseases, such as heart attack, stroke or blindness. This diagnosis benefit can be combined with further benefits if the disease is well-controlled. Unlike life-style benefits, there is a certain risk that such a prevention benefit attracts lives with less-than-average health status, so the amount payable and other elements – such as sales channels – need to be balanced.

Both the lifestyle benefit and the early diagnosis benefit can lead to an improved communication with the customer, which is valuable. The insurer learns more about the customer and can use the information to enhance its offers to the customer. In turn, the customer has a strong partner with aligned interests who helps to prevent diseases or their sequelae. In a nutshell, medical progress has drastically changed the appearance of cardiovascular diseases over the past few decades and this has not left the definition-based product CI insurance untouched. The various needs of different markets and different customers do not allow a one-size-fits-all solution, but strategic decisions can help to manage the different demands. While sedentary lifestyles can lead to problems not only for insurers but society as a whole, increased client interaction and prevention tools give insurers a chance to play their part in helping their customers lead a healthier life.

Gen Re has been involved in the design and definition of Critical Illness insurance since the launch of the first product. Please do not hesitate to contact us if you are looking for a trusted and knowledgeable partner to assist your product development.