-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Demographic Change in Mexico – An Opportunity and a Challenge for the Insurance Industry

April 23, 2019

Dr. Antonio Monroy

Region: Latin America

English

Español

The most recent demographic data published in Mexico allows us to analyse in detail the profound demographic transition that has been taking place in the country for more than four decades. It is possible to develop forecasts for the future on the basis of this historic experience. The purpose of this article is not only to illustrate the profound demographic change in Mexico – and what it is expected to experience over the coming decades – but to highlight the challenges for the insurance industry posed by the various demographic trends. Wherever challenges are found, however, opportunities also exist, provided the industry succeeds in adequately transforming its own processes and meeting the needs of a changing market.

Demographic change in the past

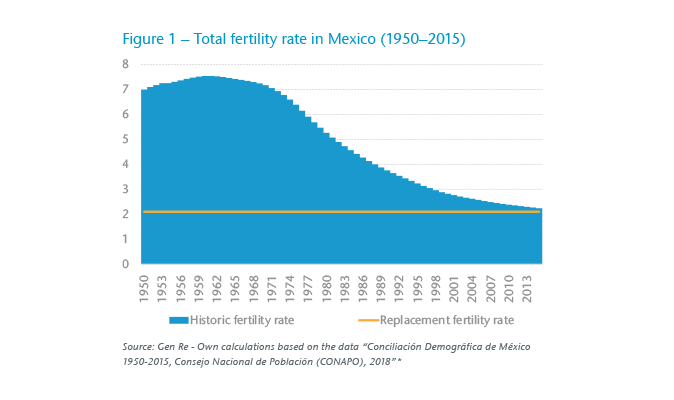

Falling fertility rates are a well-known phenomenon in virtually every country that has experienced a given degree of industrial and digital transformation.1 What is striking is the speed at which this fall has taken place in many Latin American countries, including Mexico. Whereas the total fertility rate in Mexico averaged 7.35 children per woman between 1950 and 1970, by 2015 the figure had fallen 70%, to just 2.2 children. This represents an annual fall of 1.8% over a 45-year period (1971–2015). The short-term projections of the Mexican National Population Commission (Comisión Nacional de Población – CONAPO) indicates that the total fertility rate will fall below the replacement rate of 2.1 children during the current year of 2019. The replacement rate is the theoretical fertility rate that would permit a closed population to remain constant over time. The speed at which the total fertility rate has fallen in Mexico is noteworthy when we take into account that the fertility rate in Germany fell by an average of just 0.6% per year between 1955 and 2010.2 In other words, the same change has been occurring three times as fast in Mexico as in Germany. (Figure 1)

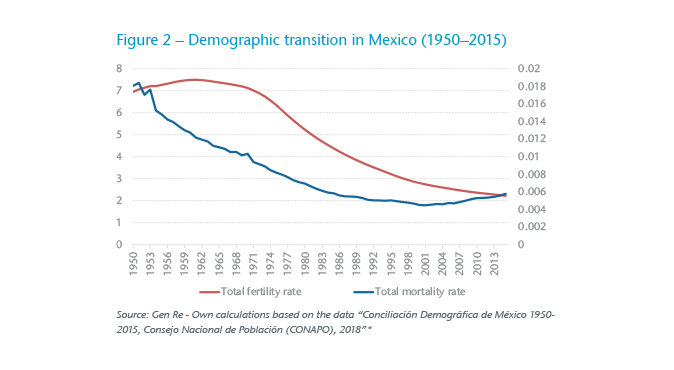

As we can see from Figure 2, the fall in the fertility rate was preceded by a notable fall in the total mortality rate. Between 1950 and 1990 the mortality rate in Mexico fell at a rate of 2.9% per year, before stabilizing and then showing a slight rise due to the general ageing of the population. A fall in mortality rate followed by a fall in fertility rate, as shown in Figure 2, is a phenomenon that has been observed in many other countries and that is traditionally described by different models of demographic transition.3

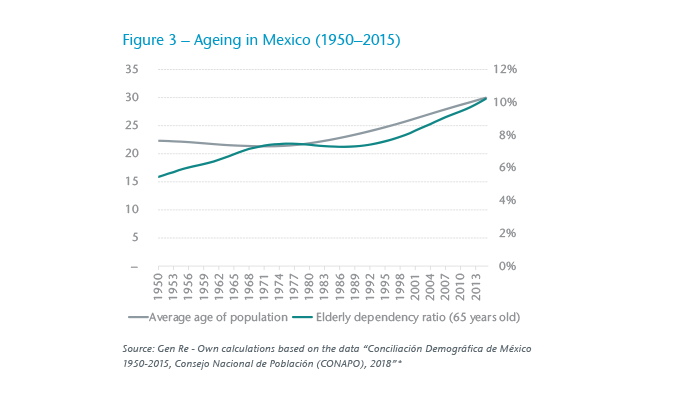

Clearly the combination of the two phenomena has led to a general ageing of the population. The average age of the population rose from 22.3 years in 1950 to 29.97 in 2015 (see Figure 3). Whereas the average age remained constant, or even fell slightly, between 1950 and the mid-1970s, it began rising in linear fashion from 1975 onwards. Similarly, if we assume 65 as the retirement age and 15-years-old as the start of working age, the ageing process may also be observed via the elderly dependency ratio.4 This ratio is the ratio of the economically inactive population (namely, given our assumption, the population older than or equal to 65-years-old) to the working age population. This ratio grew from 5.44% in 1950 to 10.21% in 2015. In other words, whereas in 1950 there were 18.37 persons of working age for each retired person (assuming retirement at the age of 65), in 2015 there were only 9.79 persons, or slightly more than half the 1950 number. This can be seen from the elderly dependency ratio shown in Figure 3.

Migration as a factor contributing to the ageing of a population

Mexico has traditionally been a country of high net negative migration, with the United States being the principal recipient of Mexican emigrants. In countries that have fertility rates falling short of the replacement rate and also low mortality rates, the migration factor plays an important role, which may or may not accelerate demographic transition. In the case of Mexico, migration is a phenomenon that exerts additional pressure on the ageing of the population.

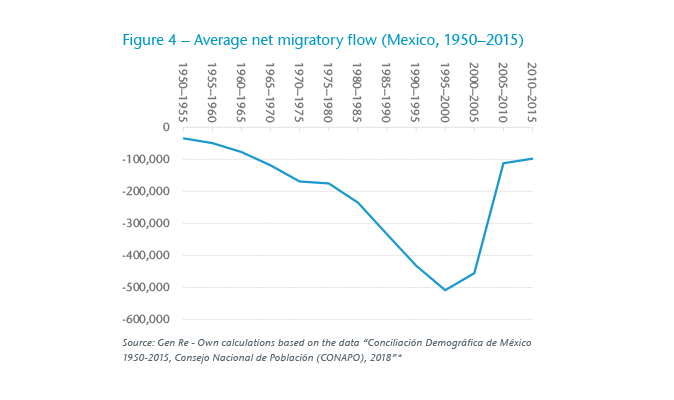

Figure 4 shows the average net annual migratory flow by five-year periods from 1950 to 2010 between Mexico and other countries. This net negative flow grew steadily from 1950 onwards, reaching a peak between 1995 and 2000 before falling from 2005 to 2016. This fall was largely due to a tightening of U.S. immigration policies from 2008 onwards, which has led to an increased flow of immigrants returning to Mexico.

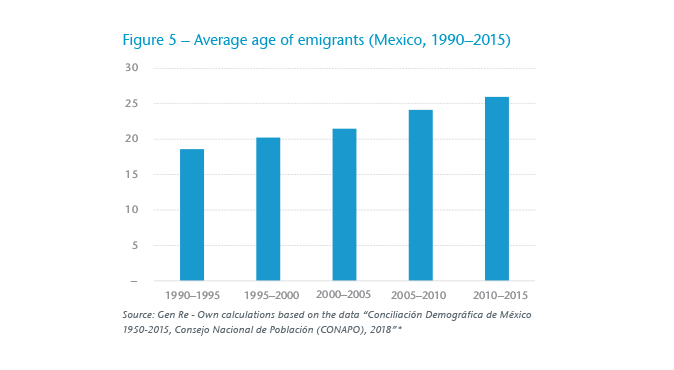

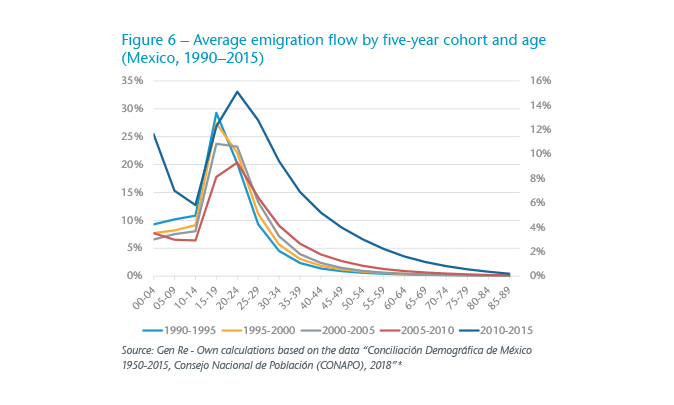

The figures show that the majority of those leaving the country are very young persons – between 20 and 30 years old – although the mix has changed over time, as Figures 5 and 6 demonstrate.

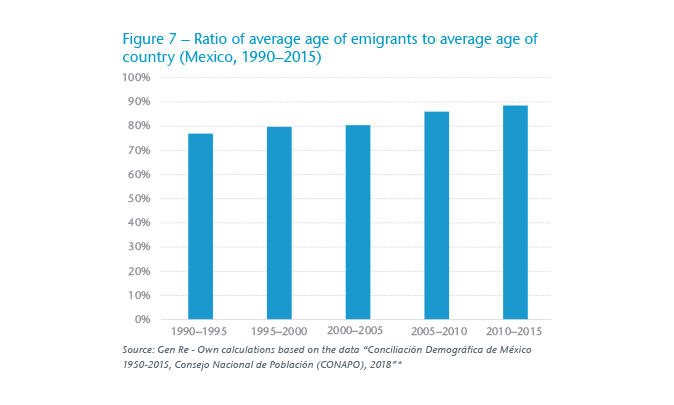

The increase in the average age of emigrants over the past 25 years can partially be explained, at least until 2010, when it reached its high point, by the natural ageing that Mexico was undergoing. This can be seen from Figure 7, which shows that the ratio between the average age of the emigrants and the average age of the Mexican population remained almost constant from 1990 to 2010. Changes in immigration policies from 2008 onwards have brought in their wake a change in the age structure of emigrants.

Having analysed the past, we shall now focus on a discussion of various projected scenarios for the short-, medium- and long-term foreseeable future.

Mexico in the future

So far, we have been discussing the demographic change Mexico has undergone since 1950. However, a more interesting question, at least from the viewpoint of the insurance industry, is what Mexico will look like in 30 or 40 years’ time. In the first instance, the answer is clear: in all probability, society will continue to grow older. However, to what extent will this be the case?

One way of answering this question, at least in approximate fashion, is to use a cohort-component model in order to project the population. In its simplest version, such a model can be used to estimate the population in year t as the sum of the population in year t-1 plus the births during year t-1 and t. We then subtract deaths from this total and add the net migratory flow observed during the year. The official population projections published by CONAPO may be approximated via this model, using 2015 as the base year and making the following assumptions:

- A linear fall will take place in the total fertility rate of 1.05% per year (taking 2.15 children per woman as the starting point and arriving at 1.70 in 2060).

- On the mortality component side (used to estimate deaths during each year of the projection), our approximation of the official model assumes a constant 1.08% annual improvement in the mortality rates.

- Finally, the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía – INEGI) assumes an increase by a factor of two in the future net migratory flow as compared with the estimated flow in 2015. Our model introduces this change in linear fashion via the projection.

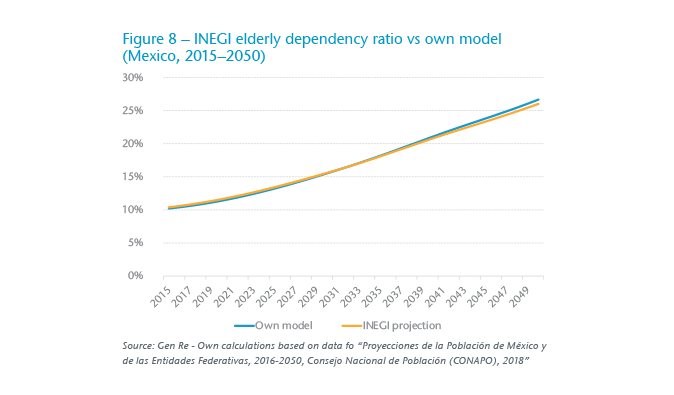

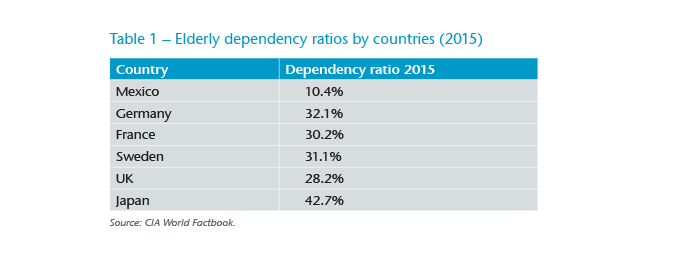

Figure 8 compares the elderly dependency ratio estimated on the INEGI projection base with the approximate dependency ratio arrived at by applying our cohort model as described above. In both models, the ratio is forecast to grow from 10.21% to 26.7% by 2050. That is, by 2050 there are expected to be 3.8 persons of working age per pensioner (assuming a constant retirement age of 65). To put this figure into perspective, it suffices to glance at Table 1, where we can see similar current elderly dependency ratios in various European Union countries, as well as in Japan, the longest-lived country in the world.

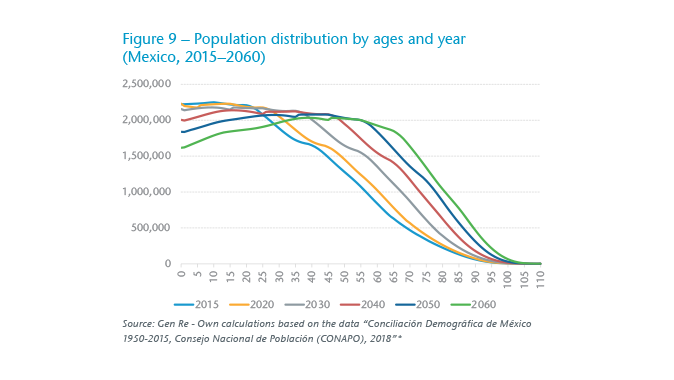

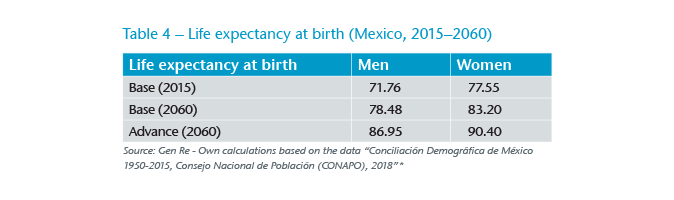

Figure 9 graphically demonstrates the anticipated ageing of the Mexican population. Whereas the 2015 life expectancy at birth in Mexico was 71.7 for men and 77.5 for women, under the assumptions made for our base model, life expectancy at birth in 2060 will be 78.48 for men and 83.2 women, a net increase of 6.7 and 5.6 years respectively.

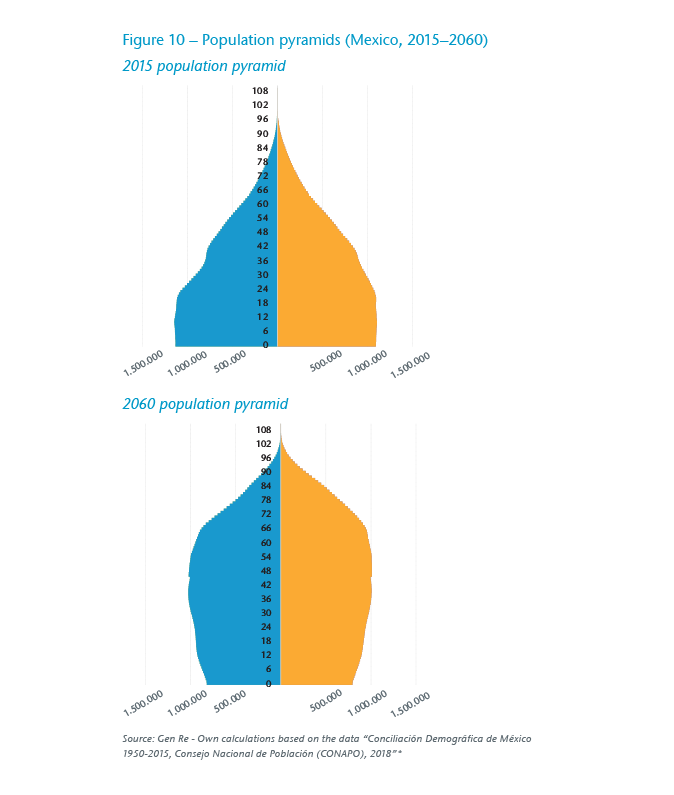

The ageing expected in the population can also be represented by means of population pyramids, which show a clear trend towards inversion of the population pyramid for 2015 (Figure 10).

Like any long-term projection, the forecasts of Mexico’s future demographic situation depend on the assumptions made for the purposes of the model. Accordingly, it is of particular importance to analyse different scenarios in order to attain a higher degree of certainty concerning the projections made and the possible future scenarios.

Different future scenarios

Taking the scenario described above (the Base scenario) as our starting point, we shall now analyse four further scenarios in which we vary one assumption at a time while leaving all the others constant. The variables analysed are:

- The annual improvement in mortality

- The total fertility rate assumptions,

- The migratory flow

- Pension age

Below we discuss each of the scenarios analysed.

Advance Scenario – In our Base scenario we assume an improvement in mortality of 1.08% p.a. To test the elasticity of our model with respect to this variable, we analysed the assumption that [there would be] an as yet-unknown spontaneous technological advance bringing about a substantial improvement in the diagnosis and cure of illnesses currently considered incurable, such as certain types of cancer. In this scenario we assume a consequent improvement in mortality of 2.5% p.a. This improvement is assumed to be constant throughout the projection period.

Reduced Migration Scenario – Currently Mexico experiences a negative migratory flow of approximately 100,000 people. This is a significant number when we consider that cities such as San Pedro Cholula (Puebla) or Tula de Allende (Hidalgo) have populations of roughly 100,000. There are indications that U.S. immigration policy could become more restrictive in the short to medium term. Given that the U.S. is the principal country of destination for Mexican emigration, we shall analyse a scenario in which it gains complete control over illegal migration, leading to a neutral annual flow of zero from 2020 onwards.

Uncontrolled Migration Scenario – The average net migratory flow reached an annual peak of -500,000 people during the five-year period from 1995–2000. In this scenario, we assume socio-economic disorder within Mexico, leading to a major rise in illegal emigration and a negative net annual migratory flow reaching -300,000 per year from 2020 onwards and then remaining constant until the end of the projection. We further assume that the age structure and sex of the emigrant/immigrant population remains constant and as observed in 2015.

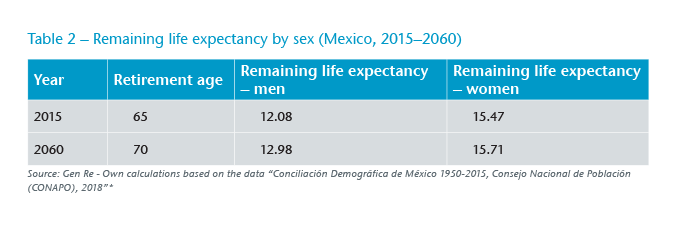

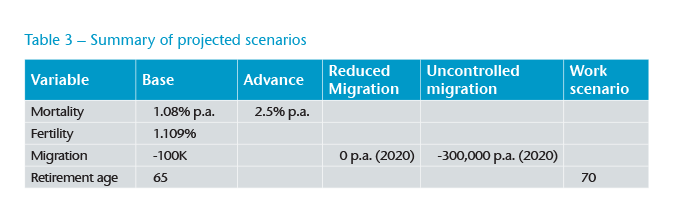

Work Scenario – At the moment, the official retirement age in Mexico is 65. Politicians are currently discussing increasing the retirement age in order to ease the financial pressures that are caused by the ageing population and that are faced by diverse social security and pension payment schemes – for example, the Mexican Institute of Social Security (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social – IMSS) system. To visualise the impact of increasing the retirement age on the population structure, we assume an incremental increase in the retirement age of one year every five years, starting from 2020, until reaching a retirement age of 70. This is a realistic scenario if we take a look at the differences between the remaining life expectancy after retirement in 2015 and 2060 respectively within the Base scenario. As can be seen from Table 2, on average men would be living 11 months longer and women almost three months longer after their retirement in 2060 than they would be given their remaining life expectancy after retiring in 2015.

For greater clarity, Table 3 summarizes the changes made in each of the scenarios analysed.

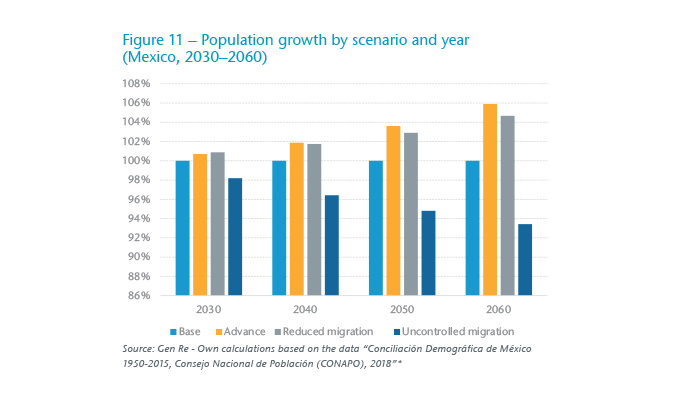

Impact on population growth

The Base scenario forecasts population growth of approximately 0.52% p.a. between 2020 and 2060. In Figure 11 we can see the difference in population size between each scenario and the Base scenario in various different years of the projection. It is interesting to note how the scenario that features an increase in the improvement in annual mortality (Advance) has a similar effect in terms of the projected population size on the scenario in which the net flow of migration is zero (Controlled Migration). Both scenarios involve an increase up to 4% greater (2050) as compared with the absolute population size in the Base scenario. Also noteworthy is the fact that a negative migration flow (Uncontrolled Migration) would lead to a population reduction of 7% by 2060. In other words, by that year there would be roughly 10.3 million fewer people than under the base scenario.

Impact on life expectancy at birth

As might be expected, the only scenario that alters life expectancy is the Advance scenario since it is the only one that alters the assumptions regarding the annual probability of death and therefore of a person’s survival.

As can be seen in Table 4, the Base scenario predicts that life expectancy by 2060 will have increased by 6.7 years among men and 5.6 years among women. The Advance scenario predicts an increase in life expectancy over 220% greater than in the Base scenario, yielding respective increases of 15.18 years among men and 12.85 years among women.

It is important to note that living longer does not automatically entail that the period of life free from illness also increases. In the literature, it is customary to refer to the difference between “life span” and “health span”, in order to highlight precisely this difference between a long life and a long and healthy life.

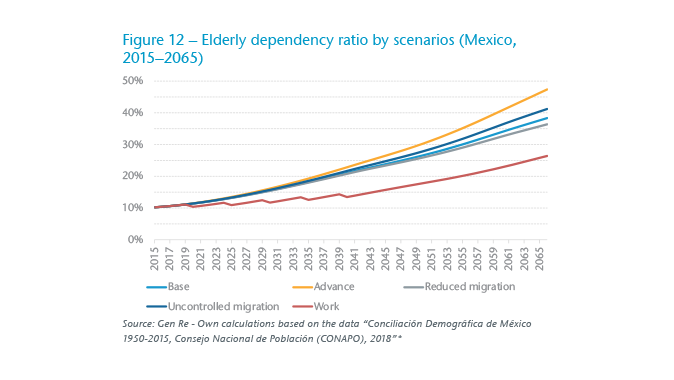

Impact on the elderly dependency ratio

The elderly dependency ratio, defined as the ratio of retired people to people of working age, is a good indicator of the expected burden that the working age population will have to face in relation to the people who have ceased working. This indicator is crucial for fixing and financing budgetary expenditure on education, health and pensions, as well as other social security outlay.

Projections of dependency ratios are very sensitive to the input parameters for the model employed. In our case, the Advance scenario involves a 2060 dependency ratio, which is some 20% greater than in the Base scenario. The models featuring different migratory flows (Reduced Migration and Uncontrolled Migration) have a lesser impact as compared with the Base scenario (of 96% and 107% respectively). As we saw previously, these scenarios do have an impact on absolute population size, but they do not substantially alter the population’s age structure.

As can be seen from Figure 12, the scenario that has the greatest impact on the elderly dependency ratio is the Work scenario, which involves an incremental increase in the retirement age from 65 to 70 up until 2040. This scenario leads to a 2060 dependency ratio of 23%; in other words, a rate almost 33% lower than in the Base scenario and 44% lower than in the Advance scenario. This scenario exemplifies the fact that increasing the retirement age could represent the most effective means of counteracting the economic effects that could arise from an ageing society.

The panorama outlined above raises various issues of importance for the insurance industry. Below we shall take a more detailed look at various different aspects.

Opportunities and challenges for the insurance industry

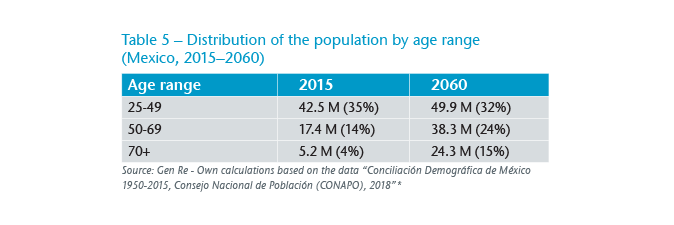

Changing target population

The potential market for insurers will undergo major change over the coming decades. As we can see in Table 5, following the projection of our Base scenario, the population aged 50 or over will grow by 2060 by 39.3 million people, while the population of young people (from age 25 to 49) will only grow by 7.4 million. The absolute growth of the age ranges is not the only important factor. The proportion of the population aged 50 and over will grow from 19% in 2015 to around 40% by 2060. In other words, almost half the population will be 50 or over.

This anticipated change represents a challenge to the insurance industry for various reasons. Firstly, it will be necessary to develop suitable cover for an elderly population. Various elements of the design of current products, such as the maximum ages of entry and of cover, will have to be adjusted to cater for the anticipated increase in life expectancy. This will entail different challenges given that available claims experience is limited as the current focus within the target population is rather different.

Secondly, it will be necessary to design and offer attractive products at affordable prices. It is important to take into account the fact that the disposable income in Latin America, which retired people have available for insurance, is limited. The OECD5 estimates for Mexico that, under the present pension regime, an average contribution of 6.5% would enable a salaried person to achieve a replacement rate of just 26% by the time of retirement. Accordingly, affordable cover for the real needs of retired people will be needed. This process of creating an adequate range of products to offer will have to be accompanied by efforts to educate consumers on the financial risks which longevity entails, and hence on the need to make suitable provision to minimise that risk. Indeed, a study published recently in Austria looking at people aged between age 50 and 79 found that 67.7% of those interviewed fear physical disorders, pain and illness, while 62.9% also had concerns about their mental health and were frightened of suffering from dementia.6 This percentage rose further (71.2%) among people over 70.

Changes in the risk profile

It is highly likely that in future there will be people actively working who would today be considered retired. Accordingly, we may expect a change in the risk profile of insurance portfolios in the form of higher sums insured on elderly people.

In life and health insurance, medical underwriting is currently a process with a variety of functions, for instance:

- Identifying risks which will require special terms, such as an increased premium, reduced benefits, or modified cover

- Classification of risks in order to ensure appropriate pricing

- As far as possible, matching the assumptions made in the pricing with the risks taken on

- Avoidance of uninsurable risks

- Guaranteeing that there is a suitably insurable interest, e.g., financial underwriting

The morbidity of many illnesses, especially chronic ones, increases with age. Accordingly, an ageing population throws up additional challenges that entail extending the functions of insurance underwriting. Emerging technologies mean that it is already possible today to identify segments within a portfolio with a lifestyle that is conducive to chronic health risks.7 Integrating this kind of service into an insurer’s own range of insurance policies allows the insurer to design personalised measures that will incentivise and promote a more healthy lifestyle. This could undoubtedly lead to the stabilisation of the state of health of an ageing portfolio.

Diversification of sales channels

Recent years have seen a growth in the importance of new sales channels, such as the Internet or, more recently, mobile applications. These channels coexist with traditional sales channels such as agents or bank insurance channels. Each of the sales channels has different target users. Whereas the younger generations gravitate more towards telecommunication media, the elderly population has a greater tendency to remain loyal to traditional sales channels. In future, as the general population ages, it will be important to take into account the sales channel preferences of the different age groups in order to avoid excluding a significant proportion of potential insured persons who are unfamiliar with certain channels. In other words, although certain channels may be more cost effective, we cannot forget that they may also have limited reach when it comes to an ever more elderly population.

New and more complex products

A growing life expectancy will probably change the type of products offered on the market. A person who expects to live longer will be more interested in products that confer benefits while alive and less in those that insure against his or her death. Accordingly, we will see a growing demand for policies that transfer the risk of longevity to the insurer, such as annuities, long-term care insurance and products with a savings component. In health insurance products, we will see more extensive ages of cover. Similarly, we shall see growing demand for policies that grant wider cover for the treatment of illnesses, many of them chronic, which tend to manifest themselves at advanced age, such as dementia or Parkinson’s disease. The inclusion of treatments and therapies that arise due to scientific advances, at reasonable prices, will be key to adapting the policies offered to a population with different needs.

Among the range of current protection insurance focusing on an elderly population, we may highlight the following ideas:

Over-50 life cover – This range of products has become increasingly popular in the UK. This type of insurance involves guaranteed acceptance cover, meaning that there is no kind of underwriting – either before or at the time of the claim – with a level premium, for the purpose of providing a modest sum insured to persons who are between 50 and 80 years old and who would not be eligible for insurance under a normal medical underwriting regime. The aim of such policies is to provide funds for such things as funeral costs or the payment of debts outstanding at the time of the policyholder’s death.

Long-term care – In Latin America we can currently see the first products venturing into the field of disability cover geared towards elderly people who have retired from working life, in which the benefits (a fixed sum insured or a temporary annuity limited to a few years) are activated by the continuous and permanent failure of different (usually three or four out of six) activities of everyday life (ADLs), even with the use of suitable aids. These activities are normally defined as follows:

- The ability to move from one room to another across a flat surface

- The unaided ability to wash oneself

- The unaided ability to dress oneself

- The ability to consume drinks or eat, once the food or drinks have been prepared

- The ability to get in and out of bed, a chair or a wheelchair

- Continence

Many chronic illnesses present in old age entail an inherent risk that the sufferer will lose physical abilities and that this will prevent him or her from living a normal life (defined as the performance of the ADLs. This kind of policy is clearly designed to provide the financial aid necessary to initially fund the lifestyle changes necessary to maintain a decent quality of life.

Specialised cover for people with chronic illnesses – Particularly in South Africa, life and disability products designed specifically for people suffering from diabetes or HIV have become very popular. Previously, these risks were considered uninsurable or at best only acceptable with great underwriting efforts. However, medical advances have not only allowed these to be converted into insurable risks but even to allow these risks to be accepted rapidly and with surcharges which are geared to the actual state of the illness in question, therefore better reflecting the condition of the person seeking insurance. In future it is highly likely that medical advances will permit the insuring – at reasonable premiums – of risks, many of them age-related, which are at present regarded as uninsurable due to the extent of the risks.

Products geared to biological age – Generally the terms and conditions of an insurance policy are geared to the actual age of the insured person, on the assumption that age itself is a factor indicating the insured person’s actual state of health (at least from a statistical viewpoint). In other words, the older a person is, the greater the risk he or she is deemed to represent (whether of death or disability), and this is therefore reflected in the policy premium. Currently, though, cover can be found that goes beyond mere age and takes different factors into account (including on a regular basis), which could be better indicators of health (that is, indicative of a given physical or biological age) and, accordingly, of the risk to be insured. These factors may include the following:

- BMI

- Systolic and diastolic pressure

- Triglycerides

- Cholesterol (HDL & LDL)

- ALT, AST & GGT

- HbA1c

- Glycosuria and Proteinuria

Specialised medical expenses products for persons of advanced age – In certain countries, such as the U.S., we find major medical expense products designed specifically for the needs of people over 50. Clearly, the modules making up such products will differ from those required by younger people. For example, whereas the maternity or child care modules would no longer be required by an elderly person, the insurance profile would be oriented more toward areas covering joint or hip problems or perhaps cardiothoracic surgery.

Challenges and opportunities for pricing

For insurers, longevity risk is the risk that their insured lives live longer than expected. This is a risk which, if any of the scenarios projected above were to become reality, could have a major impact on the profitability of a product should the various guarantees (e.g., level premiums, ages of cover, etc.) have been inadequately priced, or should reality fail to conform to the initial assumptions; for instance, due to a greater than expected reduction in mortality. Moreover, under a Solvency II regime, all the guarantees, including those relating to longevity risk, come at a price, reflecting the increased capital requirement. Accordingly it is necessary to apply models that allow for:

- Improvements in mortality

- The dynamic between the demographic variables and their impact on the various risks assumed

- The economic environment and backdrop, as well as their impact on the different variables

It is clear that those insurers who succeed in better understanding risks and have greater analytical capabilities will be able to make more informed decisions and offer their customers better products.

Conclusion

Over the past few decades, Mexico has undergone a profound demographic transformation. Mortality rates tumbled between 1950 and 1990, while the same period also saw a rapid fall in fertility rates. Both factors, combined with the phenomenon of migration, have contributed to the ageing of the Mexican population. Various projections demonstrate that this trend will continue over the coming decades and will reach levels that can already be observed in certain countries of the European Union. This societal change will bring with it a corresponding change in the target market of insurance companies, both in terms of its composition and in the type of products required. Not only the design but also the pricing of products and underwriting of risks will increasingly have to focus on an ageing population. Moreover, in order to remain sufficiently competitive through stable premiums, insurers will have to develop underwriting mechanisms aimed at promoting and maintaining health within an ever more elderly portfolio. The future will pose challenges. However, every challenge also offers growth opportunities and mutual benefits that can be shared by the insurer and the insured.