-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

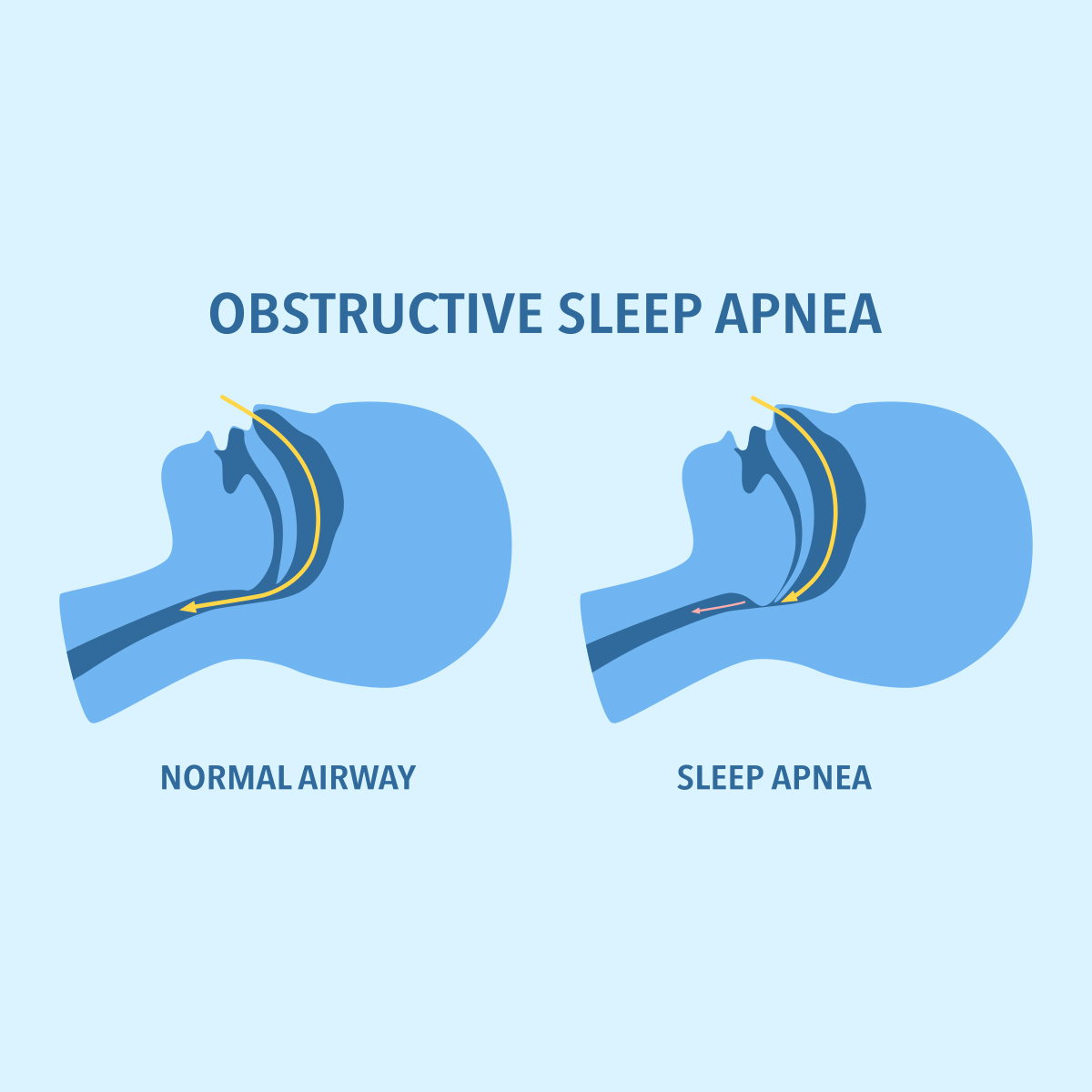

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Healthy Food and Exercise Can Reduce Our Risk of Cancer

July 03, 2018

Ross Campbell

English

Chinese

We are increasingly encouraged to be healthy. Government advice, advertising, peer pressure, and social and media messages all promote its benefits: Good health follows if we avoid sugar, quit smoking and eat less processed meat in favour of vegetables. Exercise and physical activity are not just good for the soul; a little positive thinking can give a boost to the immune system.

But what does “good health” really mean? A simple definition is being in good physical condition, but in analysing an insurance applicant’s risk, does this imply a particular weight, size in clothes, or a body free from heart disease or cancer? After all, cancer remains a leading cause of death, not to mention a significant chunk of payments made under Critical Illness insurance policies worldwide.

Each person’s interpretation of what it means to be healthy is shaped by a unique combination of physical, mental and emotional characteristics that we call lifestyle. How we choose to live has a direct impact on health outcomes that are linked to diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular and respiratory disease.

Some insurance programmes already promote behavioural change by offering rewards for physical activity. Although no science lies behind 10,000 daily steps, evidence indicates that inactivity increases the risk of ischaemic heart disease, stroke and diabetes. Moderate and vigorous exercise helps with energy, balance and weight control - and can protect against obesity, which is also linked to certain cancers.

The numbers for cancer are growing but more people than ever survive the diagnosis, thanks to improved detection and more effective treatments. However, the direct and indirect costs of cancer remain significant. Between 30% and 50% of the most common cancers may be preventable through changes in diet, weight and exercise and avoiding unhealthy exposure. While people increasingly shun tobacco, this cancer risk is being displaced by inactivity and body fatness; smoking is responsible for 54,000 new UK cancer cases annually but overweight is closing in second with 23,000.1

A new resource, the Continuous Update Project (CUP), part of the World Cancer Research Fund, helps make sense of these risks. CUP systematically evaluates global scientific evidence on how diet, nutrition, physical activity and weight affect cancer risk and survival. CUP’s careful assessment of the most recent research can help determine how to minimise the risk of developing the disease.

The latest CUP report “Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: a Global Perspective” was published in May 2018.2 It reports consistent evidence of “exposures” linked to cancer development - exposures that include diet, body fatness and the effects of physical exercise on the biological mechanisms. Exercise reduces visceral fat, improves insulin sensitivity and enhances DNA repair mechanisms, all of which decrease carcinogenesis. A nutrient-dense diet brimming with vitamins and fibre is favourable to one featuring too much salt, sugar saturated and trans-fats. The findings on alcohol, however, show the greater the consumption, the greater the risk of cancer.

For insurers thinking of customer engagement programmes, confirmation that a healthy pattern of physical activity and diet decreases cancer risk is helpful. The CUP recommendations are intended to be adopted as a lifestyle package and the report offers insights into what this could look like. Another important outcome is that CUP helps direct future cancer study to plug research gaps. This will lead to more effective understanding of the underlying biological mechanisms that link pre-clinical cancer models to long term health strategies and improved outcomes for survivors.

Endnotes

- Cancer Research UK.

- Available online at dietandcancerreport.org.