-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Biometric Information Privacy – Statutes, Claims and Litigation [Update]

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves?

Publication

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Illinois Changes Stance on Construction Defect Claims – The Trend Continues

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Four Aspects of the Current Debate

Publication

Battered Umbrella – A Market in Urgent Need of Fixing -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Underwriting High Net Worth Foreign Nationals – Considerations for U.S. Life Insurance Companies

Publication

Group Term Life Rate & Risk Management – Results of 2023 U.S. Survey

Publication

Trend Spotting on the Accelerated Underwriting Journey

Publication

All in a Day’s Work – The Impact of Non-Medical Factors in Disability Claims U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

Marginal Gains in the Medicare Supplement Market -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Why Antimicrobial Resistance and Agricultural Biosecurity Must Be Thought of As Enterprise Risk

August 07, 2018

Melissa S. Hersh, Hersh Consulting, LLC (guest contributor)

English

Français

Unmitigated antimicrobial resistance will increase global mortality and morbidity from currently treatable illnesses and diseases. Concomitant with direct human losses from treatment deficits, human consumption of antimicrobial-resistant animals and plants will indirectly amplify human losses, as well as negatively impact animal welfare and the environment. Although the threat from antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is real and warrants global attention, the strategy and narrative of how to mitigate these risks is predominantly limited to the development and humanitarian sectors. As a result, an echo chamber has emerged.

The public health, veterinary, and associated policy communities are focusing on promoting antimicrobial use (AMU) stewardship, the need for more- and better-funded research and development (including medicines, diagnostic tools, and vaccines), and access to affordable treatment. Despite increasing attention to the emergent AMR risk, the response to the existing strategy and narrative has not been successful.

What is missing is not only treating the business risk associated with AMR as enterprise risk but looking at AMR holistically as enterprise risk, in which the insurance industry should play a role. The effort to counter AMR is not just about saving lives, but also about preventing losses, including economic ones.

The management and mitigation of cyber and information risk provides one of the best comparisons for how to manage and mitigate AMR risk. The two risks are similarly complex, diffuse, interdependent, and constantly evolving. This article will look at the experience of using enterprise risk management to address cyber and information risk and to draw relevant lessons, guidance, and recommendations for addressing the AMR threat. The goal is to apply and discuss these lessons in the context of AMR.

In short, the dominant AMR strategy and narrative is too limited, and the dominant response is failing. Hence, we need a broader strategy and narrative and better response. It is time to look at AMR as enterprise risk.

Assessing the threat from AMR

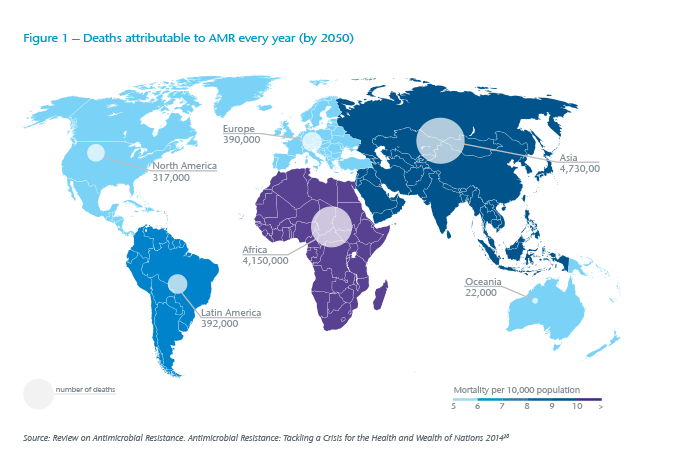

Antimicrobial resistance (see Box 1) is an emerging risk, threatening both agricultural biosecurity and human health.3 This risk is a direct consequence of antimicrobial use, or often misuse (AMU).4 AMR and AMU are widely acknowledged to be in large part a result of human behaviours. However, AMR is also a natural biological occurrence.5 AMR microorganisms occur in humans, animals, and crops. At times, there is a convergence between agricultural AMR and human food consumption, thereby creating a separate subset of risks known as foodborne AMR that comes with its own set of animal and public health impacts and agricultural biosecurity vulnerabilities.6 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), AMR is one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development today.7 (See Figure 1)

High-consequence animal infectious diseases of any origin in wildlife, livestock, and poultry can cause supply chain disruptions. Significant production losses can have direct and indirect (secondary and tertiary order) economic and political impacts that are wide-ranging and potentially long-lasting.8 For example, grain and feed producers, logistics and port operators are susceptible to upstream losses if livestock or poultry requires culling due to a devastating animal infectious disease; the billions of dollars lost from ineffective biosecurity has been demonstrated time and time again.9 Additionally, trade restrictions directly linked to the production of animals with excessive antimicrobials are likely to continue to be an issue – one that might actually incentivize positive AMU trends.10

Preventing or mitigating the risk of AMR is a persistent challenge for the medical and veterinary professions, the farming and food production industry, and the pharmaceutical industry. In characterizing the AMR threat, there is near universal consensus. According to the findings of one study, “This phenomenon, coupled with a dry antibiotic pipeline, has led the World Health Organization to warn of a ‘post-antibiotic era where common infections and minor injuries can kill’”.11 Clearly, AMR is a challenge across socio-economic and national development lines. Despite the scope and magnitude of this complex global challenge, it is anticipated that the burden – direct and indirect – of AMR will have the most significant impact on low and middle-income countries (LMIC).12

Additionally, research findings support a correlation between AMR in LMIC and out-of-pocket health expenditures for countries that require public sector medication copayments.13 The conclusion of one study found that this relationship was driven by countries that require those copayments. It also suggested that “cost-sharing of antimicrobials in the public sector may drive demand to the private sector where supply-side incentives to overprescribe are likely heightened and quality assurance less standardised.”14

AMR explained

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) refers to the resistance that microorganisms – such as bacteria, fungi, viruses and parasites – develop to withstand the effect of medicines, leading to antibiotic-resistant infections. Human-borne antibiotic resistance can affect anyone, of any age, in any country. It occurs naturally, but misuse of antibiotics in humans, animals and crops (foodborne AMR) is accelerating the process.

A growing number of infections – such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, gonorrhea, and salmonellosis – are becoming harder to treat as the antibiotics used to treat them become less effective. Antibiotic resistance leads to longer hospital stays, higher medical costs and increased mortality. Moreover, this resistance increases the likelihood that patients will forego necessary procedures and operations because of decreased efficacy of antimicrobials, which may over time increase indirect costs.

On the agricultural front, discussions about implementing agricultural biosecurity best practice – or the practice of ensuring sustainable capacity to prevent, rapidly detect, respond and mitigate against animal infectious diseases that can adversely impact draft animals, animals for consumption, animals for export, and public health (diseases that transmit to humans, known as zoonoses) – do not always have an impact on behaviours, even though they are changeable. Many of the losses associated with these risks are preventable.1

The World Bank projects that by 2050 AMR will cause global GDP to fall by between 1.1% and 3.8% as the volume of real exports also shrinks. The decline in global livestock production could range from a low of 2.6% to a high of 7.5% per year. Increases in global healthcare costs may range from USD 300 billion to more than USD 1 trillion per year, with an additional 28.3 million people falling into extreme poverty.2

In OECD countries, it is anticipated that AMR will increase the frequency, intensity, and cost of hospital admittances. It is predicted that, on average, hospitals will spend an additional USD 10,000 to USD 40,000 per patient.15 Indirect costs that will accrue from longer hospital stays or mortality rate increases include loss of productivity and income, while national healthcare budgets (where they apply) will be directly impacted. According to the OECD, given current resistance rates, “[T]he total GDP effect in OECD, accounting for increased healthcare expenditure, would amount to USD 2.9 trillion by 2050.”16 Today, drug-resistant infections are said to account for 700,000 annual deaths, and are expected to reach 10 million by 2050 and cumulatively account for USD 100 trillion in losses.17

Economic data in support or opposition to the continued use of antimicrobials in livestock for growth production is insufficient. Furthermore, there are insufficient data sets to quantify the impact of resistance in humans stemming from the use and consumption of antimicrobials in livestock specifically, and agricultural products generally.18 Going forward, more and better data are needed.19

Surveillance is essential for assessing AMR spread, informing policy and making decisions about infection control and prevention responses. The WHO highlighted the need for a common approach in 2014. Since then, it has launched a monitoring collaboration, called the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS). A total of 50 countries were enrolled by the end of 2017 but many others face difficult challenges to build national collection systems.

GLASS combines data from laboratories, together with epidemiological, clinical, and population-level data, in a standardized way. The WHO hopes the strengthened database this will create will provide a better understanding of how human health is affected by AMR, and allow for better analysis and prediction of trends. Initially, GLASS will combine AMR data for bacteria – such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae and others – that cause infections in humans. A first report was published by the WHO in January 2018.20

The call to action has been sounded globally in the food and agricultural sectors with a particular focus on countries where, concomitant to surveillance deficits, there are also regulatory and legislative gaps. However, the onus is not wholly on governments, and there is indeed recognition by – if not a plea to – producers, traders, and other stakeholders in the value chain to collect more data.

According to the OECD, “There is also insufficient data to develop global maps of antimicrobial resistance in livestock and humans, which would otherwise enable accurate comparisons between humans, livestock species, industries, countries or regions.”21 This has been echoed by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, which stated that “only 42 countries in the world have systems to collect data on the use of antimicrobials in livestock.”22

While surveillance requires data, not all data is equal. The veracity, volume, variety, and velocity of data that can be collected seem daunting and time-intensive. For AMR, two parallel surveillance systems are needed: one for monitoring and detecting changes in AMU and one for monitoring and detecting changes in AMR. Additional, specific surveillance systems need to be established to address the relationship to foodborne AMR and impacts on human consumption.

Substantial business interruption costs are likely if animal slaughter, food production, or a food recall is required. Additionally, downstream effects can include loss in market share, reputational losses, reduced movement of people, reduced investments, unemployment, banned exports, food systems insecurity, and political instability. Moreover, increasingly, there is a possible risk of deliberate disinformation campaigns being used to foment and foster dissent and divisiveness, and to undermine economic stability. It is reasonable to assume that the likelihood of subtle state and non-state influence operations used to highlight AMR as well as to focus attention to agricultural diseases is a natural evolution of this threat vector and – like antimicrobial resistance – requires monitoring.23

Generally, antimicrobial drugs have helped combat infectious diseases that were lethal in the recent past. In agriculture, antimicrobial use can make sick animals healthy and even enhance productivity in crops, livestock, and aquaculture. In humans, complex surgery, organ transplantation, and cancer treatment could all be at risk if antibiotics no longer combat the effects of harmful pathogens. As AMR develops, the ability to treat infections diminishes, and the risk increases for the spread of persistent infections.

New thinking needed on risk

Antimicrobial use (AMU) and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) are a global challenge. AMR is not only a public health risk it, is also a business risk. Efforts to raise awareness and curb behaviors to limit indiscriminate and injudicious use of antibiotics are overlooking the role that the insurance industry can play in positively modifying behaviors and incentivizing adherence to professional best practices. The insurance industry has a unique opportunity to get ahead of an emerging risk, and to positively contribute to shaping thought leadership, including framing the potential suite of losses in the health, life, property and casualty areas that will arise from AMU and AMR – even if AMR in part is a naturally occurring phenomenon.

In looking at how to approach the risk narratives for AMU and AMR, and develop associated controls to reduce losses through a combination of risk transfer and mitigation measures, it’s possible for the insurance industry to turn to lessons being learned in how to manage cyber risk. Both cyber and AMR risk can be characterized as having systemic exposures with cascading impacts. Like unmitigated cyber risk, AMR risk can and does result in physical, operational, financial and reputational losses. While there is no panacea for cyber or AMR risk, there is much that the insurance industry can do to help the international community to bound and articulate the risk exposure and loss landscape from these risks by contributing to the development of a common lexicon for each.