-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

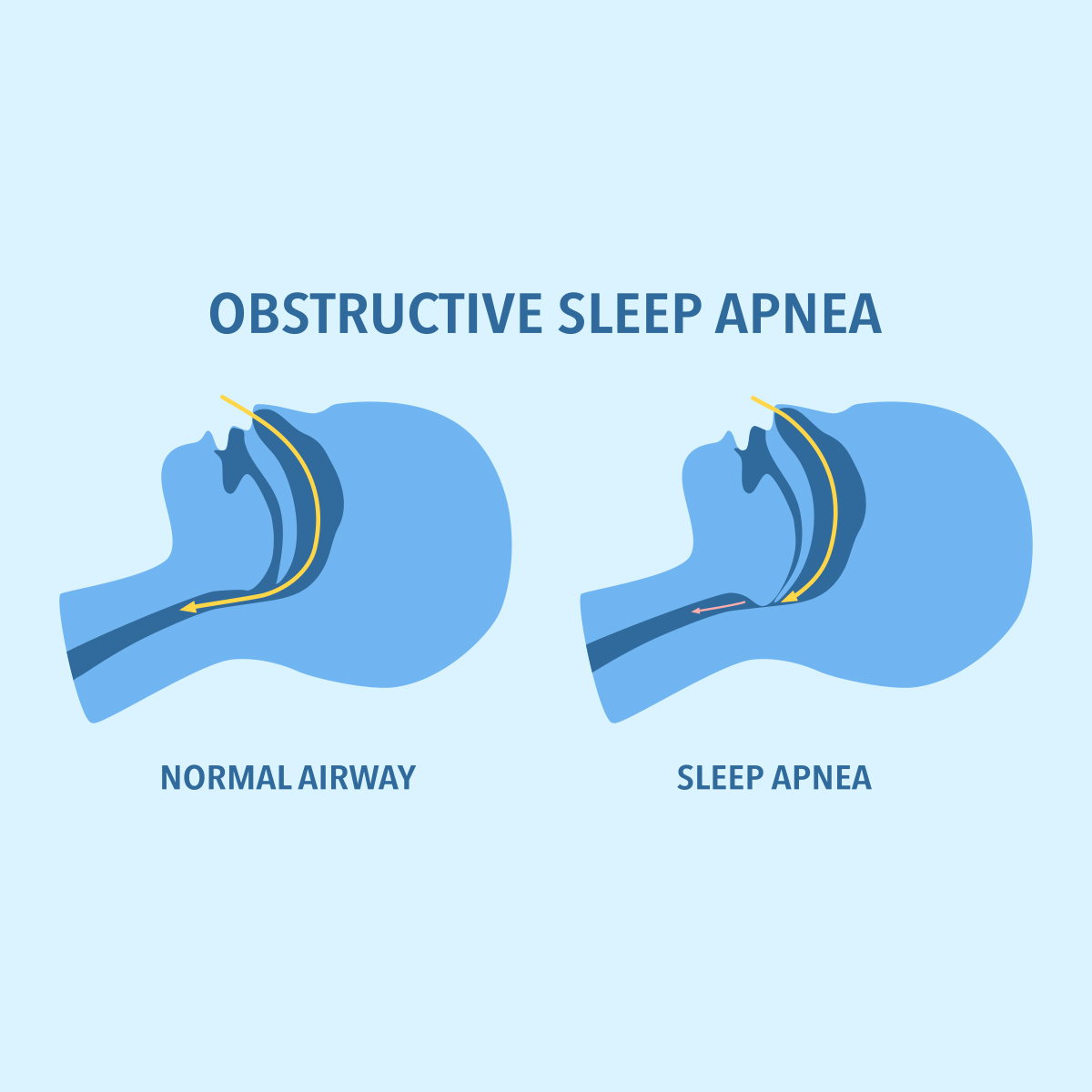

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Solvency II – Why We Must Be Rational When Comparing Solvency Ratios

September 13, 2016

Dr. Jonas Kaiser

English

Deutsch

Solvency II compels insurance and reinsurance companies to deal with risk measuring and management. It fosters internal and external communication about risks, thereby improving risk management standards across the industry.

The Solvency Ratio is certainly one of the most eye-catching figures in the Solvency II (SII) framework. Yet its use as a measure to compare the capital strength of companies does run the risk of oversimplifying things.

Already today, ahead of the start of mandatory disclosure in 2017, Solvency Ratios considered “too low” when compared to market expectations (but still well above the required threshold) have affected the share prices of some companies.

But no single figure can be used to determine whether a company has a sound capital base, good risk management and a low probability of default. This requires a deeper understanding of different aspects. We would encourage you to look at the numbers closely.

The equation behind the Solvency Ratio is straightforward enough. It is the ratio of Own Funds (OF) to the Solvency Capital Requirement (SCR).

Own Funds (OF) refers to the eligible capital according to the SII Economic Balance Sheet, which evaluates assets and liabilities at market values.

The Solvency Capital Requirement is the capital required to have a 0.5% probability of default within the next year, according to the SII Standard Model.

It is worth remembering that the SCR is not the actual required capital to have a 0.5% probability of default but the output of a model. While this may sound obvious, it is surprisingly easy to forget. Similarly, according to the SII model, Own Funds are not equal to the capital that would actually be available.

We would still have to tread carefully even if we took the model outputs for granted. After all, the probability of default is what really matters. According to the model, a Solvency Ratio of 100% corresponds to a 0.5% probability of default over a 12-month period. However, for Solvency Ratios other than 100%, there is no distinct link to the probability of default. This can lead to unexpected outcomes.

Imagine that two companies, A and B, publish Solvency Ratios of 200% and 175%, respectively. At first glance, Company A appears more secure. However, Company A may have more exposure to extreme events than Company B and therefore require more excess capital or a higher Solvency Ratio than Company B to achieve a probability of default below 0.5%. (see graph below)

Company B’s probability of default is about half that of Company A’s despite having a lower Solvency Ratio.

The Standard Model has a “one size fits all” approach for all insurance industry companies across the EU - be it mono-liners, life, health, non-life insurers or reinsurers. It is difficult for such a model to capture all the differences in these businesses. It might work well in some cases but be extremely inaccurate in others.

As a result, not every company uses the Standard Model. Some have developed and adopted a certified (partial) internal model or plan to do so. This makes sense if the (partial) internal model better reflects the company’s risk profile but it does further complicate the comparability of results.

Finally, we shouldn’t forget about the volatility of model outputs, which can be quite sensitive to small changes in certain parameters, some of which are beyond the control of companies (such as interest rates or the value of the stock portfolio on the measuring date).

The authorities are aware of this, and that is why the Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA) is an integral part of Solvency II. Each company is required to provide its own view of its own risk. Furthermore, additional information beyond the Solvency Ratio (e.g., the economic balance sheet) will be publicly available and should provide a clearer picture.