-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Six Things We Can Do to Curb Legal System Abuse

Publication

Is Human Trafficking the Next Big Liability Exposure for Insurers?

Publication

When Likes Turn to Lawsuits – Social Media Addiction and the Insurance Fallout

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance

Publication

Creating Strong Reinsurance Submissions That Drive Better Outcomes

Publication

Do Commercial General Liability Policies Cover Mental Anguish From Sexual Abuse? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Group Medical EOI Underwriting – Snapshot of U.S. Benchmark Survey

Publication

Next Gen Underwriting Insights – 2025 Survey Results & Confusion Matrix Considerations [Webinar]

Publication

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists – From Evolution to Revolution U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

Always On: Understanding New Age Addictions and Their Implications for Disability Insurance

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Disruptive Innovation – Coming to Life Insurance Near You

June 17, 2016

Louis Rossouw

English

Chinese

The New York Times was struggling online. While the quality of its journalism was not in doubt, the company’s digital business was shrinking, as measured by subscription numbers and advertising revenues. A “new ideas task force” was formed to address the challenges the news organisation faced; fortunately, for us at least, their conclusions were leaked online in 2014.1

The initial focus of the task force had been to develop a new product to resolve the issue of their flagging digital business, but on digging into the detail the ambit changed to something much broader: “…helping The Times adjust to this moment of promise and peril, we concluded, would have greater journalistic and financial impact than virtually any product idea we might have suggested.”2

Much has been written about the report and the glimpse it offers into a large organisation seeking to respond to new competitors that threaten it because of their better use of new technologies.3 The conclusions it draws make interesting reading even to such news industry outsiders as life and health insurers.

The Innovator’s Dilemma

The authors of The New York Times report reference “The Innovator’s Dilemma”, written by Clayton Christensen, which develops a concept called “disruptive innovation.”4 More recently, Christensen summarized disruption as a process whereby a smaller company with fewer resources is able to successfully challenge established incumbent businesses.5 The company entering the market can be successful because the incumbent is busy improving its products and services only for its existing customer base.

Typically, an incumbent business works to service only those customers that provide its main source of revenue and profit. This leaves unserved segments of the market – gaps that a new and more nimble entrant can focus on servicing, usually with an offer of a cheaper, if inferior, product or service not yet targeted to this segment.

As time goes by, the new entrant may improve its quality while keeping costs low. It begins to threaten the incumbent’s business by luring away customers with a “good enough” offering that is cheaper or more convenient. This is when “disruption” occurs.

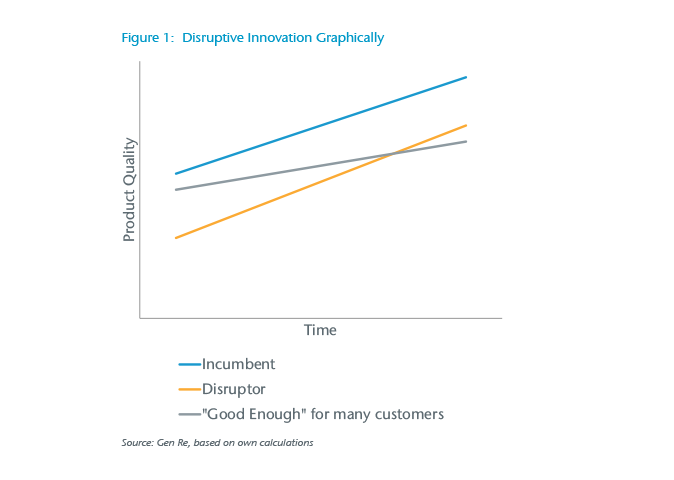

Represented graphically, it might look like Figure 1. The disrupter starts with an inferior product appealing to segments of the market overlooked by the incumbent. As the inferior product becomes “good enough” for many customers to use it, the incumbent provider faces losing significant market share to the disruptor.

An example of disruption is what happened with film cameras, which for many years were the top product for taking quality photographs. As the first digital cameras became available, they only produced inferior pictures to photo film ones. As technology improved, digital cameras could eventually produce images that were “good enough”. While not of the outright quality of top-end film cameras, for most consumers the convenience of the digital format far outweighed the benefits of using photo film.

The story does not end there, of course; digital cameras are now built into most smartphones. While consumers may have doubted the necessity, the image quality soon became “good enough” for many to abandon even their digital cameras; the disruptor became the disrupted. Although customers remain for digital and photo film cameras, they exist in smaller numbers and in niche use cases. This mass of disruption was not without corporate victims; Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2012 after failing to respond adequately to competitors.

In its report, The New York Times task force cited the example of BuzzFeed using social media distribution as a potential disruptor to its own news business. BuzzFeed is a global network for news and entertainment made up of articles and videos available on mobile devices. While the BuzzFeed offering – its news content – may lack the journalistic quality of The New York Times, it provides content to a market segment underserved by the newspaper online. BuzzFeed has continued to improve its offering to the point that it has proved “good enough” to attract 6 billion monthly views; in the process certainly luring The New York Times’ customers.

We can also differentiate between “low-end” and “new market” disruptors. Low-end disruptors, like BuzzFeed, enter the low-quality, low-price end of a market and grow from there. In contrast, new market disruptors grow by attracting customers who have not previously used a particular product or service. An example of new market disruptor might be a budget airline that gets people flying who would not have considered it before, perhaps due to cost. This type of disruptor starts out by expanding the market rather than by luring customers from incumbents.

An important determinant of whether new entrants will be disruptive is the pace of their technological development. They are more likely to prove disruptive if they are able to improve their product rapidly without incurring the same cost base as the incumbents.

Battle for the customer interface

Tom Goodwin of TechCrunch, a news group that follows start-up companies, describes a new breed of company that is emerging: “Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate. Something interesting is happening.”6

Goodwin says that while much of the world’s economy was built on large organisations with extensive supply chains and complex distribution channels to the customer, the fastest-growing companies in recent times are instead “interface owners.” New breed companies like this operate through a thin layer (interface) that sits in front of the supply chain. They extract value from relationships with customers, not by altering the product or service so much, but by changing the interface.

Where new interface owners emerge, a commodity market for suppliers of the actual products develops in parallel. The vehicle owners and drivers of Uber, the apartment owners on Airbnb, and all the content that gets produced by people and organisations (including traditional media like The New York Times) that gets shared via such social media as Facebook are all part of this market.

Take the example of Uber. It supplies a taxi service essentially like any other (you pay to be driven from A to B) but the ease of interaction and its interface is where the value lies. To assess the interface worth, consider that after seven years of operation Uber is already valued higher than General Motors, Ford or Honda.7

Christensen commented that he found Uber is not disrupting taxi business. Its customers are provided a higher quality service than most established taxi business and targeted existing users of taxis. This is not the traditional disruption as he defines it. However, when we consider Uber as being a disruptor of car ownership, the model seems to fit a lot better. This may also explain why Uber’s valuation is being compared to the likes of General Motors and Ford.

Either way, while it’s a company that may not strictly fit Christensen’s definition of disruptive innovation, its success is hard to ignore.

Disrupting insurance?

The New York Times faced a similar battle over the interface. Its problem was, to an extent, one of distribution. It needed to pump out its news in a way that customers would place value on it. The high quality of the product itself was no longer enough to achieve this. It is easy to see similarities with traditional insurance companies: large organisations (typically) using well-established models and processes of business face challenges adapting to new and rapid changes to the consumer, technology and business environments.

Life and health insurers are yet to feel much pressure from disruptors because many are still developing models and approaches or are catering to the low-end and to the never-insured parts of the market. But these companies have started, and solutions are being developed. They have the advantage of being without legacy processes, and are thus likely to improve much faster than insurers, albeit from a lower base.

Many disruptors focus on distribution – particularly the interface, or interaction, with the customer and trying to make it easier for people to buy insurance. Developments in the UK market highlight this. Much of the business of life insurance is now conducted through online aggregators and broker portals providing quick and easy price comparisons and these, to an extent, have replaced insurance brands and commoditised insurance companies’ products.

Technologies

Technology is integral to disruption – driving it, as Christensen sees it – and is central to the development of customer interfaces (for smarter distribution). There are large trends here that are likely to create disruption in insurance for years to come.

Probably the first technology trend in insurance to consider is the use of data analytics to better understand customers.8 It is credible that analysing data effectively is the key to delivering consumers a better experience, especially in sales and in the underwriting process. To some extent all the technologies and behaviours described below take data analytics as their base line.

Mobile technology is an important shift in both behaviour and technology, with smartphones and tablets now used more than ever. Devices generate and store invaluable and unique information about customers, and integrating insurance products with them will be increasingly important. In some markets this is the only way to reach people cheaply and effectively, which means there is huge potential in Mobile First platforms targeted at the developing world.

Wearables, an extension of mobile technology, are a potential driver of disruption in life insurance.9 Wearable technology will allow life insurers access to better information, particularly about the health and lifestyle habits of applicants and policyholders.

Wearables and mobile technology lend themselves to the fast-developing concept of wellness management. Discovery’s Vitality insurance program, which promotes the concept backed by data from wearables, is the vanguard of a trend other providers are starting to follow.10 Wellness management extends from general fitness into disease or “condition-specific” observation; for example, a person with diabetes using an application on a device to monitor blood sugar.

Behavioural science is another “technology” that is being used to improve the user interface to make sure consumer and insurers get what they want using influence and incentive techniques.11

The Internet of Things (IoT) allows devices to connect, send and receive data. As a parallel to health monitoring using wristbands, telematics boxes are already prevalent to monitor driver behaviour in motor insurance, while the IoT-connected home also presents opportunities for insurers.12

The potential of mobile money is already opening financial services to those with no access to formal banking; in some African countries, for example, the M-Pesa service has a stronghold. New forms of money transfer, payment and financial technology present opportunity; Vodafone, for example, has 25 million mobile money platform users.13 This flexible development represents an opportunity for insurers, especially in developing markets. Other Fintech developments extend to payments, remittances, peer-to-peer lending, financial advice, budgeting apps, Bitcoin and blockchain technology, which holds the promise of distributed ledger technology in financial services.14

Peer-to-peer approach, being explored in lending, is also garnering interest in insurance. There are some start-ups focussing on peer-to-peer insurance where smaller groups share some risk, which is also how insurance started.15 There is also distribution of insurance in a peer-to-peer manner.16

Chat (and message bots) is also starting to emerge as a new way to think about distributing insurance.17 Consider the prevalence of services such as WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger; why can’t we just chat to our insurer and get financial advice? It is often difficult to convince people to install an app and go through some effort to get it set up. Chat is a much more immediate and natural way to interact with customers.

The above, combined with a renewed focus on artificial intelligence, is leading to the focus on robo-advisors. This could be delivered by an app, on the Internet or as mentioned, via chat interfaces. This shows promise in the lower income markets where paid advice models are too expensive to be successful.

Where to next?

The New York Times responded to being faced with large numbers of competitors by taking on new technology and distribution approaches. How did they fare? Firstly, contrary to some beliefs, they seem to have implemented the points of the report, and online traffic is up.18 This is a hopeful development in the face of disruption and indicates that incumbents are able to respond.

Christensen says that “universally effective responses to disruptive threats remain elusive”.19 He goes on to say that their current thinking is that incumbents may need to establish separate divisions to tackle or exploit a new disruptive business model.

Much of The New York Times’ problems stemmed from having a culture supporting print and having to protect the existing revenue sources. This occurred to such an extent that the digital-only subscription was more expensive than a print and digital subscription. They seem to have tackled this problem from within.

As insurers, we also have cultures based on existing channels and distribution that produce much of our revenue, resulting in our missing opportunities elsewhere. That is probably why some insurers are establishing separate units and new brands for new business models.

What is certain is that insurers will be facing significant disruptive business models in the near future. There will be existing insurance companies that do not respond quickly enough, but there will also be those that end up paving the way for new ways of doing insurance business.

One positive outcome of all this jostling is that the customer is bound to get an ever improving experience of insurance and, in the end, is that not the best outcome?