-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Secondary Peril Events Are Becoming “Primary.” How Should the Insurance Industry Respond?

Publication

PFAS – Rougher Waters Ahead?

Publication

Risky Left Turns – What About a Roundabout?

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

Focus Groups and Shadow Juries – Telling a Persuasive Story for Trial -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Cardiovascular Disease Deaths in Young Adults – A Tie to Substance Use?

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Ups and Downs of the U.S. Group Term Life Market U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

New Life & Health Technologies – A Double-edged Sword? -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Have Psychiatrists Learnt To Think Yet? DSM-5 and Medicalising of Everyday Life

January 08, 2014

Dr. Chris Ball

English

Nearly 100 years ago Karl Jaspers, a German psychiatrist and philosopher, published his influential work “Allgemeine Psychopathologie” (General Psychopathology, Jaspers, 1913, translated 1997).2 It stimulated a debate about the evaluation and classification of psychiatric disorders. Frustrated by the positions taken by his contemporaries, he asked when psychiatrists would “learn to think”. The controversy that surrounded the development of the latest edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), shows Jasper’s question remains relevant today.3

Kendler et al. (2012) posed a related question asking, “What kinds of things are psychiatric disorders?”4 They concluded there is no consensus as to the best answer. Psychiatry is not alone in having problems defining diagnoses. Ask, for example, how fat is obese, what level of Tropinin confirms a heart attack or if CKD (chronic kidney disease) stage 3 is a diagnosis? Yet psychiatry is singled out as having the greatest difficulty in this area often because biological markers used to define physical diseases are not so apparent.

The changes to the diagnostic criteria in DSM-5 offer a number of challenges. Some people will receive help they need sooner while others risk being labelled as having a mental health problem with all the attendant problems this may bring. The squabbling amongst psychiatric professionals over DSM-5 revisions seems parochial until the effect of mental health problems on the insurance industry in general, and on disability insurance in particular, is explored.

“An ideal [diagnostic] schema would have to satisfy the following requirements: It must be such that any given case would have only one place within it and every case should have a place. The whole plan must have a compelling objectivity so that different observers can classify cases in the same way.

Such a schema would only be possible if every mode of psychic disorder could be classified alongside others as a disease of an exclusive nature and so give substance to the idea of a disease entity. As this is not the case our ideal formulation has to be modified as follows:

Simple broad basic outlines must emerge clearly.

Subdivisions must be made according to their essential importance for the total concept.

Items which seem to be of the same order must appear on the same level of meaning (as to the meaning of the facts, of the concepts used and the method of investigation). Heterogeneous elements must be seen in clear contrast.

There should be no obscuring of what is still unknown. Contradictions should come clearly to light. It is preferable to have a decisiveness which provokes discontent than satisfaction with a pseudo-knowledge won by approximations and a purely logical arrangement.”

Karl Jaspers (General Psychopathology, 1913, translated 1997, page 605)

Such a schema would only be possible if every mode of psychic disorder could be classified alongside others as a disease of an exclusive nature and so give substance to the idea of a disease entity. As this is not the case our ideal formulation has to be modified as follows:

Simple broad basic outlines must emerge clearly.

Subdivisions must be made according to their essential importance for the total concept.

Items which seem to be of the same order must appear on the same level of meaning (as to the meaning of the facts, of the concepts used and the method of investigation). Heterogeneous elements must be seen in clear contrast.

There should be no obscuring of what is still unknown. Contradictions should come clearly to light. It is preferable to have a decisiveness which provokes discontent than satisfaction with a pseudo-knowledge won by approximations and a purely logical arrangement.”

Karl Jaspers (General Psychopathology, 1913, translated 1997, page 605)

Changing diagnostic criteria

Early in the development of DSM-5, a letter to the American Psychiatric Association jokingly proposed a new diagnostic entity, “the human condition”, that would include “being fidgety” and “showing off”. This diagnosis would, the author claimed, “facilitate insurance reimbursement, dispose of the bothersome problem of comorbidity, and encourage the quest for a drug to cure the disorder of being human” (Chodroff, 2005).5 On a more serious note, the British Psychological Society added that the general public is “negatively affected by the continued and continuous medicalisation of their natural and normal responses to their experiences; responses which undoubtedly have distressing consequences which demand helping responses, but which do not reflect illnesses so much as normal individual variation” (BPS, 2011).6

In response to similar concerns, DSM-5 authors offered cogent reasons for changing the criteria or introducing new disorders citing enhanced biological knowledge and the more subtle clinical data. The latter helps identify differences between disorders in terms of how symptoms cluster and behave over time. Any diagnosis that causes distress or suffering is a focus of clinical concern but it must also have practical utility for the clinician. The more cynical have even questioned the role of the pharmaceutical industry in driving the diagnostic margins to develop markets.

Absence trends

Improving European sickness absence trends suggest that, by and large, insurers could relax concerns that mental health will be a significant cause of disability claims in the future. Despite the economic impact of financial recession, sickness absence levels have been going down. Perhaps people with mental health problems are less likely to be employed when work is scarce or reluctant to admit to problems and so soldier on.

In the Netherlands, for example, rates have fallen to around 4 % from a high of 10 % during the 1980s (Klein Hesselink, 2011).7 Figures from the UK reveal that despite there being more people in work currently than in 1993 (25.3 million vs. 29.2 million), fewer days are lost to sickness (178 million vs. 131 million days or 2.8 % hours lost vs. 1.8 %). The proportion of days lost due to mental health problems is relatively small. Stress, depression and anxiety account for 13.3 million days. Serious mental health problems contribute 0.7 million (Office for National Statistics, 2012).8

Other sources suggest that any optimism may be unfounded. In Austria, for example, total days of all-cause absenteeism decreased by 13 % between 1993 and 2002 while days lost to mental health problems increased by 56 % (McDaid et al., 2008).9 A recent headline in a British newspaper proclaimed that “a million jobless get handouts for mental health” suggesting a huge rise in the numbers receiving disability benefit from the state.10 The implication is those with mental health problems are not valid recipients of state aid.

The effect of recession on mental health is most obvious in suicide rates. Stuckler et al. (2009) suggest for every 1 % rise in unemployment there is an increase of 0.79 % in the suicide rate.11 More recently his group has suggested that, on the basis of the trends since the 2008 global financial crisis, about 5000 additional suicides will be seen across the world in 2009 (once official figures are published) with increases greater in men and in particular men of working age.12

Insurers’ own figures are also of concern. Legal & General, in the UK, report mental health is the largest single cause of Income Protection (IP) claims in their group business. The assertion being that increasing pressures in the work place, changes in regulation and trying to deliver more for less “are taking their toll”. Their concern prompted the addition of a “stress toolkit” to their group product aimed at helping managers recognise how individuals approach stress and understand the best way to support their employees. Aviva reported that moderate depression (28 %) followed by anxiety (15 %) and stress (12 %) were the most common mental health causes of IP claims across their portfolio in 2011.13

In the same year, the Council for Disability Awareness, a non-profit organisation that aims to educate the American public about the risk and consequences of an income-interrupting illness or injury, reported that mental disorders contributed 9.1 % of new long-term disability claims. Looking broadly at state disability claims14 across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, 30 % to 50 % of all new claims are for mental health problems – usually “common mental disorders” – with 70 % being in young adults (OECD, 2011).15

Increased prevalence

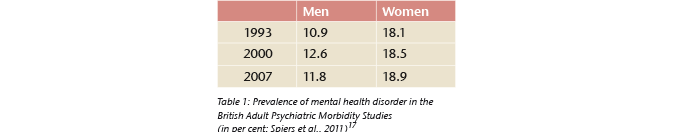

Evidence of increasing prevalence of mental health disorders is hard to come by as data to demonstrate change in prevalence over time. For example, in a U.S. study comparing years 1991-1992 with 2001-2002, the prevalence of major depression among adults was seen to increase from 3.33 % to 7.06 % (Comptom et al., 2006).16 The study used the same methodology at both time points suggesting a significant increase. However, it cannot be assumed that this rate of growth has continued to the present day. By contrast the British Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Surveys show no significant changes in the prevalence of mental disorders between 1993 and 2007 (see Table 1).

The OECD has raised concern over the numbers of young people given state disability benefits for mental health problems and the difficulty of later engaging them in meaningful work. It concluded that the prevalence of mental health disorders is not increasing but there are complex processes that serve to give that appearance.18

Increased recognition

It has been something of a truism that primary care doctors are poor at recognising mental health problems in their patients (e. g. Mitchel et al., 2009).19 Studies show enormous variations in individual practice but given the brief time most doctors get with their patients much of this criticism seems somewhat unjust. Screening for depression using defined questionnaires is recommended practice in North America, but not in the UK for example, but there are concerns about its effectiveness. Thombs et al. (2011) suggest as many as seven hundred people would need to be screened for just one to benefit clinically.20 Although this evidence could be read in a more positive light, the point is well made.

Increased treatment

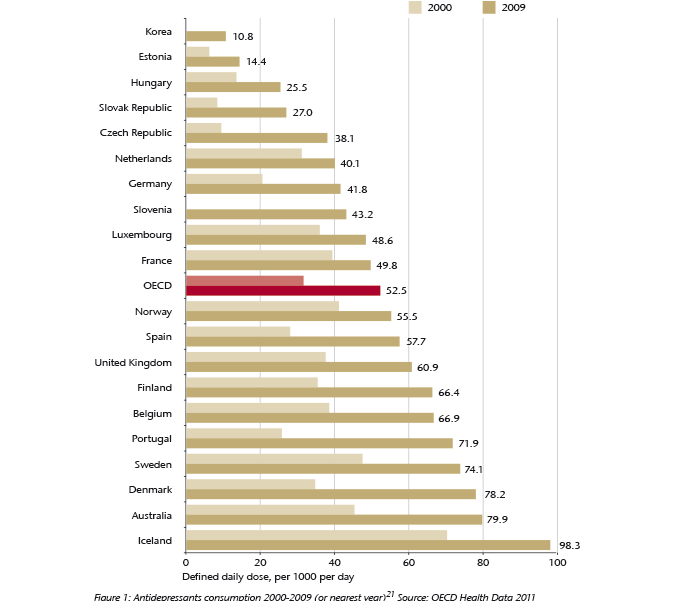

A consistent phenomenon in this context is the increasing rate of antidepressant prescribing over the ten years to 2009. On average there has been a 60 % increase according to OECD data (see Figure 1).

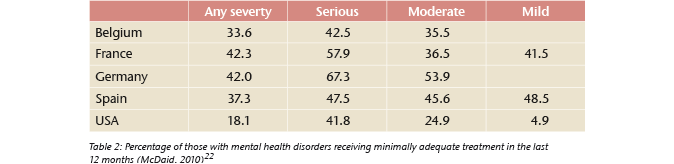

A number of interpretations have been made of these figures. One is that increased recognition has prompted more treatment and that improved side-effect profiles of new generation antidepressants make them easier to use. Another is that more people are being given medication they do not really need. Many prescriptions are short-term, so out of line with clinical guidance, but a significant proportion are for prolonged treatment. Nevertheless, a significant number of people get no treatment or the treatment they get does not meet even minimally adequate standards (see Table 2).

The rise in the number of young people receiving drug treatment for attention deficit disorder (ADHD), autism and bipolar affective disorder is striking and has raised worries about the long-term effects. The reasons for this increase in prescribing have been debated at length. Some argue for a genuine increase in prevalence, others that recognition has improved. Other possibilities are a reduction in the stigma of a mental illness diagnosis or changes in the definition of the illnesses themselves.

Increased openness

Many illnesses have moved from a stage when they could not be openly discussed, or sufferers were discriminated against or even blamed for their problems. For example the taboos surrounding a cancer diagnosis have largely disappeared, yet mental illness still carries negative stereotypes that hinder people from talking openly and seeking help. Doctors are reluctant to tender a diagnosis fearing the problems it may cause for a person; not least when they apply for insurance. There have been campaigns aimed at reducing stigma but their effectiveness is difficult to evaluate and their impact only modest at best (McDaid, 2010).

For those in the workplace, there is a suggestion that more are willing to talk about how they are feeling not only with friends (41 %) but often with their GP (26 %) who presumably can do little about a work problem. Only a small number would talk to their employers (11 %), the people who could probably effect a change, presumably as a result of the impact this will have on their future employment prospects (Aviva, 2012).23 So whilst people appear increasingly to use mental health labels for their psychological distress, they appear happier to engage with a traditional illness model and go to their doctor, rather than to their employers who actually could make a difference to their predicament.

Impact on insurance

Thinking about product design, the problem of defining illnesses is perennial for insurers because diagnostic and technical developments rapidly outstrip any future proofing written into policy wordings. Using these systems for mental health underwriting and claims meant consistency between these processes and clarity for the client. Reducing the threshold for diagnosis has the potential to label many more people’s experience as a “mental illness”. In turn more will be disclosed with the potential that the relatively trivial will be rated by underwriters as if it were a significant risk event. It also could mean that meeting claims criteria is easier.

Thinking about underwriting, despite the high profile of DSM-5 there is no imperative for its immediate introduction to insurance industry practice. ICD-10 will not be updated until 2015 at least and may not follow all the trails taken by DSM-5. There is a challenge at underwriting to collect information from the applicant in a timely and efficient way that throws light on the nature of the mental health problem that has been reported. Revising application form questions or using tele-interviews and rules engines are all possible ways forward. Perhaps too, underwriting manuals need to be much more imaginative to reflect the wide spectrum of single disorders and provide tools to aid the underwriting decision in a much more dynamic way.

Thinking about claims, until psychiatry has a Higgs boson or “eureka” moment and has a biological marker to measure severity, merely having a DSM-5 diagnosis should not be an adequate condition for claim (Craddock, 2013).24 Although ultimately subjective perhaps, lessons learnt from research about the reliable application of rating scales to disorders can be applied to ensure severity criteria are met. While a structured claims management process can significantly reduce concerns, attempts to fence off claims by product design alone should be viewed with some caution given the evolving nature of mental health. This approach may even discriminate against a significant number of the population who have a legitimate claim to the benefits that insurance brings.

Conclusion

For many, the publication of DSM-5 is a “red herring”; a distraction from the central issues of mental illness. As far as any formalised coding system is used, the ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders published by the World Health Organization is the most commonly referenced outside of North America. For most people in primary care no reference is made to either of these monolithic coding systems. However, they are both prominent in the courts and in many insurance settings.

The prevalence of mental health disorders may not be increasing but the cost, duration and proportion of disability claims that arise from these problems is. DSM-5 itself is unlikely to have much direct impact on these in most markets. However, it has sparked a significant debate, beyond the boundaries of psychiatry, which presents a challenge to the traditional mental illness models employed by the insurance industry.

The opportunity to think about the risk management of mental health by underwriting and claims processes and imaginative product design should not be put to one side just because it all looks too difficult and does not behave like a proper illness should. It may be tough to ask the industry to think about these issues when Jasper’s question still appears unanswered.