-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers?

Publication

Cat Bonds – A Threat to Traditional Reinsurance?

Publication

Decision-Making in the Age of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Publication

Buildings Made of Wood – A Challenge For Insurers?

Publication

The CrowdStrike Incident – A Wake-Up Call for Insurers?

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

When Actuaries Meet Claims Managers – Data-Driven Disability Claims Review

Publication

Chronic Pain and the Role of Insurers – A Multifactorial Perspective on Causes, Therapies and Prognosis

Publication

Fasting – A Tradition Across Civilizations

Publication

Alzheimer’s Disease Overview – Detection and New Treatments

Publication

Simplicity, Interpretability, and Effective Variable Selection with LASSO Regression Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Biometric Information Privacy – Statutes, Claims and Litigation

April 17, 2023

Glenn Frankel

Region: North America

English

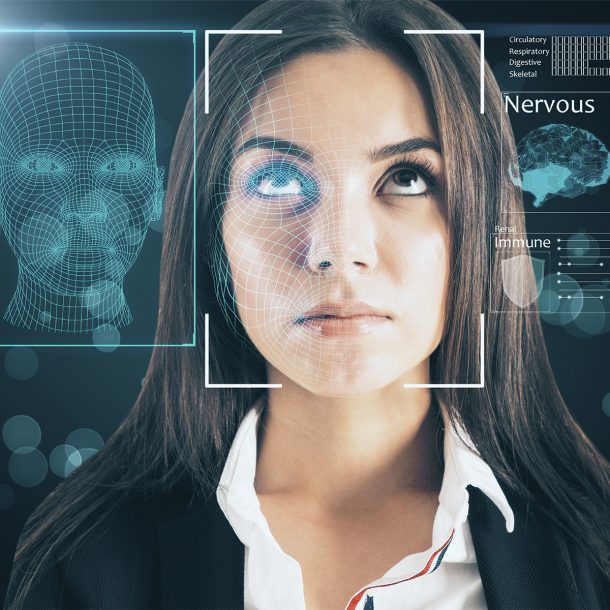

What Are Biometrics?

Biometric information is defined as the “measurement and statistical analysis of an individual’s physical and behavioral characteristics.”1 Stated another way, it is any of the measurable attributes and traits that make each of us unique. Physical biometric information may include fingerprints, DNA, faceprints, handprints, retina scans, ear features, and even odor; behavioral examples are gestures, voice patterns, typing rhythm, and walking gait.

Today, there are three main areas that utilize biometrics:

- Identification/Security Access – As opposed to swiping an ID card or using a key, biometric information can be used to access a facility, building, floor or room, and also to open smartphones, computers, and portable storage devices. Fingerprints are typically utilized, but high-security facilities may incorporate retinal or iris scanners, or other more sophisticated means.

- Time Management – For hourly employees, biometric information can be used instead of traditional clocking in and out, reducing the incidents of “buddy punching.”

- Tech/Apps – Biometric information usage is exploding in the technology sector. Examples include social media platforms (e.g., Snapchat, Instagram, Facebook), retail applications (e.g., virtual try‑on technology), and even insurance apps (e.g., using a picture of a face taken on a mobile device to receive a life insurance quote).

Benefits from biometric information usage include improved accuracy and security, fraud reduction, and improved customer experience. However, potential concerns include ever-increasing costs for technology, storage and protection, and growing privacy fears (e.g., identity theft or unauthorized disclosure or use). Unlike a password, if an individual’s biometric information is compromised it cannot be changed, so any potential damage can be more permanent and lasting.

A recent study determined that 40% of Americans use facial biometrics daily, and that number jumps to 75% for Gen Zers and Millenials.2 Overall, over 75% of Americans have had their biometric information collected (many without knowing or realizing it).3 Further, 27% of U.S. businesses utilized biometric authentication technology in 2019, and that number jumped to 79% in 2022.4 Lastly, businesses around the world spent an estimated $11.6 billion on digital verification tools in 2022; that figure is expected to exceed $20 billion by 2027.5

Legislation

At the end of 2022, 10 states had existing biometric information privacy legislation.6 Generally, the purpose of such laws is to protect the privacy of biometric information by regulating how businesses collect, use, and store such data. Of those 10, three states (Illinois, Texas, and Washington) have specific biometric privacy laws; the others have provisions built into general privacy statutes.7 Further, many additional states had proposed biometric privacy bills pending last year, so there is a lot of activity in this space. Of note, there is presently no federal law/regulation that specifically governs biometric information privacy.

Illinois – Biometric Information Privacy Act

Illinois’ Biometric Information Privacy Act, frequently referred to as “BIPA,” was passed in 2008 and was the first specific biometric privacy law in the United States.8 It regulates the collection/usage of a list of specific “Biometric Identifiers,” which includes “retina or iris scan, fingerprint, voiceprint, or scan of hand or face geometry.”9 The requirements apply to all private businesses; there are no minimum size or revenue requirements.10 BIPA’s key provisions require that companies that collect/possess biometric information:

- Notice – Provide written notice to those whose information will be collected.

- Consent – Obtain prior written consent.

- Disclose – Communicate the purpose and duration of data collection, storage, and use.

- Can’t Sell – Refrain from selling or profiting from the data.

- Written Policy – Have a written retention and destruction policy.

- Private Right of Action – Victims can sue to enforce.

- Attorneys’ Fees – Plaintiff attorneys’ fees are specifically recoverable.

- Statutory Damages – Specifically mandated statutory damages of $1,000 per negligent violation and $5,000 per each intentional/reckless wrongdoing.11

From its passing in 2008 through 2015, BIPA was largely unutilized. In 2015, class action lawsuits started to be filed, and from 2017 through 2022 nearly 2,000 BIPA lawsuits commenced.12

First BIPA Verdict – Rogers v. BNSF

In October 2022, Rogers v. BNSF became the first BIPA class action case to go to trial.13 Venued in federal court in Chicago, the plaintiff class consisted of 45,600 truck drivers who had to utilize their fingerprints to gain access to BNSF’s facility, and alleged that BNSF violated BIPA by failing to obtain prior written consent, provide written notice, and disclose the purpose and duration of the data usage and storage.14 Notably, no actual breach or tangible harm was alleged. A five-day trial ensued, and after an hour’s deliberation, the jury determined that BNSF was liable for 45,600 reckless/intentional violations.15 The Judge calculated damages under BIPA and awarded the plaintiffs $228 million (45,600 drivers x $5,000 penalty = $228,000,000).16 BNSF has stated its intention to appeal.17

On the settlement front, a number of large settlements have been agreed to date:

- Wendy’s – $5.85 million – employee timekeeping18

- Snapchat – $35 million – faceprints19

- Six Flags – $36 million – customer identification for annual passes20

- McDonald’s – $50 million – employee timekeeping21

- TikTok – $92 million – videos capture biometric information22

- Google – $100 million – faceprints23

- Facebook – $615 million – faceprints24

Court Decisions

Some notable rulings from courts interpreting BIPA to date include:

- Rosenbach v. Six Flags (2019) – Held: no actual harm required to recover under BIPA25

- Sosa v. Onfido (2022) – Held: faceprints distinguishable from photographs (excluded under BIPA), and therefore BIPA applicable26

- McDonald v. Symphony Bronzeville Park (2022) – Held: Workers’ Compensation laws do not bar a BIPA recovery27

- Vance v. Amazon and Microsoft (2022) – 2 cases venued in Washington. Held: BIPA not applicable because key activities took place outside of Illinois28

- Barnett v. Apple (2022) – Held: BIPA not applicable because touch and face ID tools were optional and the data was only stored locally on individual phones29

- Tims v. Black Horse Carriers (2023) – Held: five-year (as opposed to one-year) statute of limitations applicable to BIPA claims30

Of particular note, on February 17, 2023, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled in Cothron v. White Castle that each scan/collection of biometric information constitutes a separate violation under BIPA (as opposed to one violation per individual), potentially expanding liability exponentially for BIPA violations.31 Subsequent to the ruling, White Castle declared that its exposure to the 9,000+ employee class may exceed $17,000,000,000.32 Procedural and constitutional challenges, and potential legislative measures, are expected.

Coverage

Things are still developing on the coverage front, but most of the action to date has been under CGL policies. The seminal case at this point is West Bend Mut. Ins. Co. v. Krishna Schaumburg Tan.33 Therein, tanning salon customers’ fingerprints were used for identification purposes, and the tanning salon hired a third-party vendor to process the biometric information. Again, no actual breach to the public at large was alleged. Interpreting the personal injury definition,34 the Illinois Supreme Court interpreted the word “publication” to include communication to a single party, and determined that the hiring and sharing of the biometric information with the vendor constituted publication under the definition and found a duty to defend.35

There have also been some cases interpreting whether certain exclusions (e.g., Employment-Related Practices, Distribution of Materials in Violation of Statutes, Access or Disclosure) exclude coverage for BIPA claims, and the majority of decisions to date have determined the exclusions to not be applicable. Overall, there is still much to play out on the coverage front, including whether coverage is ultimately sought under other coverage types (e.g., Directors & Officers, EPLI, Cyber).

Biometric Information Privacy Exclusions

On March 2, 2023, ISO filed a Data Privacy exclusion, and a revision to its Access- or Disclosure-related exclusion, which includes specific reference to biometrics.36 The proposed effective date is December 1, 2023.37 Gen Re has analyzed biometric privacy exclusion options, including potential insurance policy exclusion language, and has prepared a sample biometric privacy exclusion. Please contact your Gen Re representative for more information.

Next Steps

With a private right of action, customer and employee actions permitted, no actual harm or breach required, mandatory statutory damages, and attorneys’ fees recoverable, BIPA class actions are very attractive and lucrative to plaintiffs’ class action counsel. And while there is still a lot of development to come nationwide on the legislative, liability and coverage fronts, there are things that businesses and insurers should consider now:

Businesses

- Seek legal counsel.

- Track/monitor existing and potential biometric privacy legislation where business is conducted.

- Where applicable, develop written policies that clearly comply with all statutory requirements.

- Identify where collection and/or use of biometric information is occurring as part of business activities.

- Implement appropriate safeguards. For example, limit who can access biometric data, provide proper training, store the information securely, encrypt the data, develop a response plan, run drills, etc.

Insurers

- Seek legal counsel.

- Track/monitor existing and potential biometric privacy legislation where business is written.

- As part of the underwriting process, inquire as to:

- Whether the potential insured collects or utilizes any biometric information?

- Is the potential insured aware of any pending or threatened claims relating to biometric information?

- If so, are they aware of any potentially applicable laws/requirements?

- Do they have proper compliance plans and safeguards in place?

Clearly, biometric information privacy legislation and resulting claim activity warrant close scrutiny by the insurance industry.

* This blog has been prepared for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. It is not intended to serve as a substitute for your own underwriting, claim or legal reviews.

- https://www.techtarget.com/searchsecurity/definition/biometrics

- https://www.biometricupdate.com/202211/gen-z-and-millennials-adoption-of-face-biometrics-reaches-75-percent-report

- https://imageware.io/biometric-trends-and-statistics

- https://www.biometricupdate.com/202209/biometric-authentication-use-in-us-businesses-tripled-over-3-years-to-tackle-cyber-threats#:~:text=Resources-,Biometric%20authentication%20use%20in%20US%20businesses%20tripled,years%20to%20tackle%20cyber%20threats&text=The%20use%20of%20biometric%20authentication,report%20by%20software%20expert%20GetApp

- https://www.biometricupdate.com/202208/digital-identity-verification-spending-to-pass-20b-by-2027-but-security-challenges-remain

- https://www.huschblackwell.com/2023-state-biometric-privacy-law-tracker

- https://www.troutman.com/insights/a-fresh-face-of-privacy-2022-biometric-laws.html#:~:text=Currently%2C%20only%20Illinois%2C%20Texas%2C,a%20private%20right%20of%20action

- Biometric Information Privacy Act, 740 ILCS 14 et seq.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. State or local governmental entities and financial institutions regulated by Federal law are specifically excluded from BIPA’s requirements.

- Ibid.

- https://www.reuters.com/legal/litigation/illinois-top-court-endorses-five-year-window-biometric-privacy-claims-2023-02-02

- https://news.bloomberglaw.com/privacy-and-data-security/first-illinois-biometric-privacy-jury-trial-ends-in-bnsf-loss

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- https://news.bloomberglaw.com/privacy-and-data-security/first-illinois-biometric-privacy-jury-trial-ends-in-bnsf-loss

- https://global.lockton.com/news-insights/rogers-v-bnsf-verdict-signals-companies-about-the-cost-of-violating-illinois

- https://cookcountyrecord.com/stories/607107703-chicago-area-wendy-s-franchisee-to-pay-5-85m-to-end-class-action-over-worker-fingerprint-scans

- https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2022/08/23/snapchat-illinois-class-action-lawsuit-settlement-35-million/7876602001

- https://www.sj-r.com/story/news/courts/2021/06/15/amusement-park-agrees-36-m-settlement-over-alleged-bipa-violations/7700999002

- https://madisonrecord.com/stories/619750163-mcdonald-s-reaches-50-million-preliminary-bipa-settlement-class-members-have-until-feb-9-to-file-claim-or-opt-out

- https://www.nbcchicago.com/news/local/google-facebook-and-more-a-roundup-of-settlements-surrounding-illinois-biometric-privacy-act/2923461

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Rosenbach v. Six Flags Entm't Corp., 2019 IL 123186, 129 N.E.3d 1197, 2019 Ill. LEXIS 7, 432 Ill. Dec. 654

- Sosa v. Onfido, Inc., 600 F. Supp. 3d 859, 2022 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 74672, 2022 WL 1211506

- McDonald v. Symphony Bronzeville Park, LLC, 2022 IL 126511, 193 N.E.3d 1253, 2022 Ill. LEXIS 194, 456 Ill. Dec. 845

- Vance v. Amazon.com, Inc., 2022 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 195303, 2022 WL 12306231 and Vance v. Microsoft Corp., 2022 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 189250, 2022 WL 9983979

- Barnett v. Apple Inc., 2022 IL App (1st) 220187, 2022 Ill. App. LEXIS 556

- Tims v. Black Horse Carriers, Inc., 2023 IL 127801, 2023 Ill. LEXIS 144

- Cothron v. White Castle Sys., 2023 IL 128004, 2023 Ill. LEXIS 146

- https://www.reuters.com/legal/white-castle-could-face-multibillion-dollar-judgment-illinois-privacy-lawsuit-2023-02-17

- West Bend Mut. Ins. Co. v. Krishna Schaumburg Tan, Inc., 2021 IL 125978, 183 N.E.3d 47, 2021 Ill. LEXIS 430, 451 Ill. Dec. 1

- “Personal Injury” was defined as “[o]ral or written publication of material that violates a person’s right of privacy.” Ibid.

- Ibid.

- See ISO Endorsements CG 00 69 12 23 and CG 21 06 12 23.

- Ibid.