-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers?

Publication

Cat Bonds – A Threat to Traditional Reinsurance?

Publication

Decision-Making in the Age of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Publication

Buildings Made of Wood – A Challenge For Insurers?

Publication

The CrowdStrike Incident – A Wake-Up Call for Insurers?

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

When Actuaries Meet Claims Managers – Data-Driven Disability Claims Review

Publication

Chronic Pain and the Role of Insurers – A Multifactorial Perspective on Causes, Therapies and Prognosis

Publication

Fasting – A Tradition Across Civilizations

Publication

Alzheimer’s Disease Overview – Detection and New Treatments

Publication

Simplicity, Interpretability, and Effective Variable Selection with LASSO Regression Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Underwriting Wildfire – Creating Your Hazard Map

September 09, 2019

Marc Dahling,

Gerry Hopkins (retired)

Region: North America

English

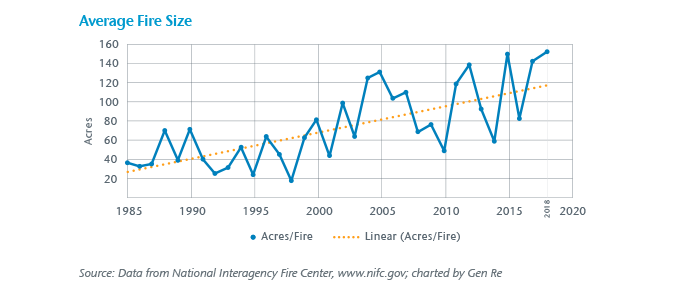

Over the last five years, we’ve seen a tremendous increase in losses from wildfire activity. That activity has been heavily concentrated in California, which accounts for seven out of the 10 largest wildfires in terms of structures impacted. That activity has also elevated wildfire, formerly considered a minor or secondary peril for insurers and reinsurers, to a primary catastrophe peril at the level of hurricane, earthquake, flood, and tornado.

Growing and Spreading Risk

A major factor in the increase in structural losses due to wildfire can be attributed to the rapid increase in structures built in the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) – defined as “a set of conditions and interactions within the built and natural environments that increase communities’ vulnerability to wildfire.”1 Unfortunately, the statistics on WUI growth are not considered a completely reliable and up-to-date record. The last formal study was released by the USDA in 2015 but it relied on 2010s “as of” data.

The normal fluctuations of climatic conditions, potentially exacerbated by climate change, have had many unexpected and unique regional impacts that contribute to increased wildfire exposure. Also, the persistent infestation of bark beetles, that appear to be leaving dead trees behind in an increasing rate, provides more fuel for wildfires. These overlapping stressors are often mentioned as causes contributing to the perceived increase in wildfire frequency and severity.

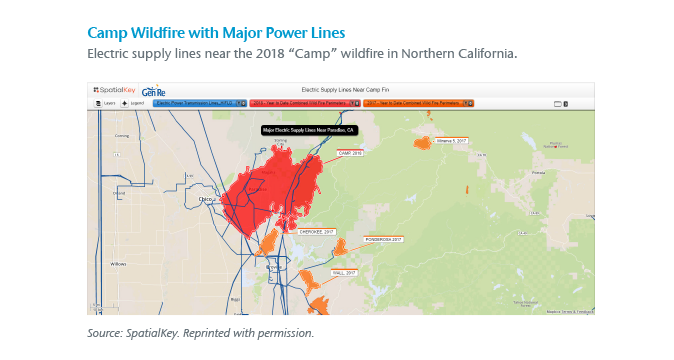

Another factor receiving a lot of attention is the impact of power utility operations and related infrastructure maintenance practices. The human element (e.g., poor forest management around power lines) has been noted as causing and amplifying initial ignition, intensity, and duration of recent wildfire events. The problem is not new. Over the last decade, legal judgments and successful insurance subrogation have obtained recoveries from utilities for wildfire damages.

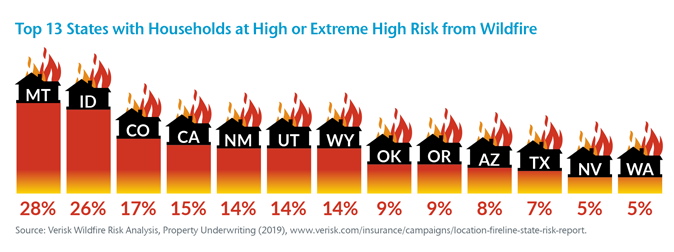

With the recent wildfire losses, California has been the focus of much of the industry’s concern – and rightfully so, given the high number of high-risk households (15% of the total number of households) in that state. However, other Western states have a much higher percentage of households exposed to wildfire at a high or extreme risk level (28% for Montana). To illustrate, see our compilation of the Top 13 states at high risk, as reported by ISO Verisk.2

Tools and Challenges

Until now, the risk evaluation and aggregation tools used for wildfire peril were, for a variety of reasons, relatively unsophisticated compared to more mature underwriting tools and models developed for hurricane and earthquake perils. Third-party modeling firms don’t spend resources developing Cat models unless there is a clear demand and financial support from the insurance industry. However, in response to increased wildfire activity in recent years, the insurance industry and third-party model vendors are now channeling more resources into improving the knowledge and understanding of this peril. The goal is the development of tools for better risk evaluation, projected loss modeling and more accurate aggregation of exposed values.

One current limitation in existing tools is the incomplete historical record of physical wildfires, acres burned, wildfire-related structural losses, and human loss of life. The reason is that there is no comprehensive consolidated dataset of historical fire activity akin to the extensive wind and storm records that can be accessed through NOAA. The most complete and consistent records are based on wildfire activity within federal lands. In contrast, many individual municipalities have their own independent protocols for fire reporting and records. They do not generally overlap and may result in significant gaps between the local and federal fire experience data.

Another weakness identified in our research is the use of traditional geopolitical map aggregation zones (county, town, ZIP code) for exposure management, as compared to wildfire peril behavior which doesn’t follow traditional map boundaries.

Wildfires tend to be rural in nature and have a high percentage of total losses to structures due to the lack of fire protection resources. Whereas other natural catastrophe perils, such as hurricane and earthquake, are predominantly partial loss scenarios spread over more loss locations and a much larger geographic footprint. The high individual loss severity characteristic of conflagration losses contributes to the relatively large dollar losses from wildfire events.

Improving Your Hazard Map

Recognizing the inherent weaknesses of existing sources and tools, we at Gen Re have focused considerable effort on finding other available data sources to evaluate and identify wildfire hazards. Our approach involves multiple tools and data sets.

Building on additional data sources and a licensed Cat model, we integrate our client companies’ risk location data with SpatialKey, a data enrichment and geospatial mapping tool, to help evaluate individual risk, as well as accumulations, across client portfolios.3 This is done via overlaying shapefiles (akin to Venn diagrams) to better identify highly-exposed areas and risk mitigation efforts.

The wildfire peril presents challenges to the insurance industry for individual risk analysis and portfolio management. We have worked with clients using spatial mapping and other tools to help analyze portfolios and to identify areas of peak exposure. If you are interested and want to explore further, please contact your local Gen Re representative today.

Here are some examples of shapefile layers (risk factors) that we have successfully employed with our spatial mapping tool:

- Company location data on a map with high-quality geocoding

- Detailed topographical maps, including slope zones and vegetation types

- Publicly available wildfire historical footprints

- Any publicly and/or privately developed hazard grading maps

- Population density and changes over time

- Maps depicting WUI areas and changes over time

- Drought area maps

- Utility service area/high voltage power line maps

- Bark beetle and other destructive insect damage (actual and expected)

- Wildfire-modeled average annual loss by risk

- Modeled accumulations

... and many more

Endnotes

- https://globalresilience.northeastern.edu/wildfire-a-changing-landscape-a-global-resilience-institute-and-national-fire-protection-association-assessment/

- Verisk Wildfire Risk Analysis, Property Underwriting (2019), https://www.verisk.com/insurance/campaigns/location-fireline-state-risk-report

- www.spatialkey.com