-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers?

Publication

Cat Bonds – A Threat to Traditional Reinsurance?

Publication

Decision-Making in the Age of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Publication

Buildings Made of Wood – A Challenge For Insurers?

Publication

The CrowdStrike Incident – A Wake-Up Call for Insurers?

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

When Actuaries Meet Claims Managers – Data-Driven Disability Claims Review

Publication

Chronic Pain and the Role of Insurers – A Multifactorial Perspective on Causes, Therapies and Prognosis

Publication

Fasting – A Tradition Across Civilizations

Publication

Alzheimer’s Disease Overview – Detection and New Treatments

Publication

Simplicity, Interpretability, and Effective Variable Selection with LASSO Regression Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

The Court of Milan Tables – Bodily Injury Compensation in Italy

July 25, 2018

Lorenzo Vismara

Region: Italy

English

Italiano

When I began my career as a Casualty claims handler almost 20 years ago, my main tool at work was a compendium of more than 120 pages, containing 20 different tables detailing compensation amounts applied by various courts in Italy. These tables often led to widely different results when assessing compensation for the same injuries. This situation was due to the lack of standardisation and regulation in this area of insurance, as well as the general development of the legal system, which was still far away from finding a unique solution for compensable items and ways to quantify the compensation due.

In the late 1970s the view began to prevail that bodily injuries should be compensated not only by taking into account the financial loss, but that all losses incurred should be compensated irrespective of the repercussions on an individual’s ability to earn an income. From this fundamental turning point, the legal system took various steps to find a solution that would allow for compensation solely based on a person’s “overall health” as guaranteed by the Constitution. Such claims could be made by any citizen regardless of the individual’s income or profession.

By the mid 1990s, the method deemed most efficient was a tabular system with calculations based on the degree of permanent disability suffered by the victim, as assessed by a forensic doctor. Given a default value assigned to each point of disability, the amount to be compensated was obtained by multiplying the number of disability points by the value of each single point. This method, simple though it may seem, was absolutely revolutionary when compared to the purely “equitable” methods used in the 1980s and early 1990s, when judges based their decisions on the amount of compensation on their own precedent cases or their subjective assessment of the facts of the case. Various adjustments were needed before arriving at the tabular methods in use today. The best known of these approaches are the Milan tables, the first edition of which was released in 1995. These tables immediately received a remarkable response and positive feedback by the claims handling community. The tabular approach made it possible to predict the amount of compensation to some extent. This had a considerable effect in reducing litigation while establishing a certain level of equality at the same time, or at least a better treatment than before when the “purely equitable” criteria were applied. However, regional differences and inconsistencies, caused by the use of tables with different values, were still possible.

The Court of Milan tables were drafted by the newly created Milan Court Monitoring Centre, a body established in 1993 consisting of magistrates, forensic doctors, law scholars and lawyers representing both insurance companies and accident victims. The Centre proposed that the value of the single permanent disability point should be determined by a progressive factor based on the severity of the permanent disability and a regressive factor based on the age of the injured person. The value of the initial point of disability should be determined by precedents decided by the Court of Milan. In the first edition published in 1995, 13 age groups were identified, with the value of each point of disability gradually decreasing by up to 60% from the youngest to oldest groups. The basic concept is still the same today, although the current tables have a different value for each year of age: Considering the potential future life of each victim, an individual who suffers an injury at a young age will have to endure the consequences of a disability in day-to-day life for a longer period than someone injured at an older age.

When compiling the tables, the Milan Court Monitoring Centre took into consideration the general development of the legal system. Applying the scheme described above, a calculation method was developed for the compensation of what was then known as biological damages (i.e. damage to the person’s “good health”, which was recognised by the Constitutional Court of the Italian Republic in the 1980s). Also, in accordance with Article 2059 of the Italian Civil Code, provisions were made for the possibility of adding 25% to 50% of the amount for the biological damage as compensation for what was then commonly known as moral damages. This assessment of moral damages as a percentage of biological damages was also applied when quantifying the amount payable to the descendants of a victim. The descendants’ compensation was based on the compensation for moral damages that would have been payable to the victim, if he or she had suffered an injury corresponding to 100% of a permanent disability.

This approach in the Milan tables was modified in 2004, when new tables were introduced that set out compensation ranges with defined minimum and maximum amounts payable to certain beneficiaries as compensation for the loss of their relatives – a system to some extent similar to what we have today. The range indicated by the tables was intended to make it easier to take into account the specific circumstances of each case with particular emphasis on the surviving relatives, whether or not these parties were living in the same household as the victim, and the quality and intensity of the emotional relationship with the deceased.

As already mentioned, in the 1990s other courts issued tables that deviated from each other in terms of structure, compensation amounts and calculation methods. The best known ones were issued in Rome, Florence, Triveneto, Turin and Lecce.

However, the Court of Milan tables have always had a considerable number of followers, given both the importance of the court and the speed at which the local monitoring centre – when adapting its own tables – incorporated guidelines issued by the Supreme Court of Cassation. The 2004 and, even more clearly, the 2009 edition of the Milan tables were both drawn up after a historical gridlock of the legal system (rulings in 2003 by the Court of Cassation, No. 8827–8828 and No. 233 by the Constitutional Court as well as rulings delivered by the United Sections on behalf of Court of Cassation Nos. 26972/3/4/5 on 11 November 2008) and reflected the new principles derived from these judgements. As a result, they had an enormous impact on other courts, which abandoned their own tables in favour of those drafted in Milan.

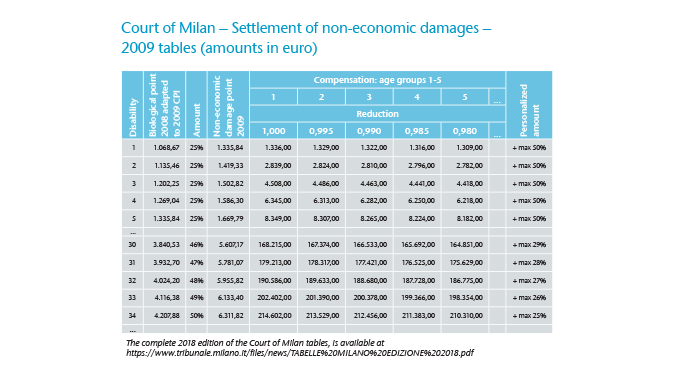

2009 changes to Court of Milan tables

The 2009 edition, in particular, introduced some highly innovative changes driven by the San Martino rulings referred to above (Nos. 26972/3/4/5 of 2008), where the Court of Cassation clearly established a division of the compensation into economic and non-economic damages. According to the ruling, the second category covers compensation types, such as biological, moral and existential damages that have a descriptive value only. Reacting rapidly to this case law, which not only provided clarity in confirming the principle but also originated from an authoritative source, the Court of Milan Monitoring Centre issued new tables in June 2009 that introduced the concept of non-economic damages.

These tables combine the two recognized compensable types of damages: the first being “biological” (defined as “permanent injury to the physical and mental integrity of the individual, subject to confirmation by a forensic doctor”, referring to anatomical, functional and interpersonal aspects of a general and specific nature), and the second being “moral” (defined as non-economic damages resulting from those same biological injury/injuries, described in terms of pain and subjective suffering). A scale for the extent of these damages was established according to the relative severity of the injury that led to a particular level of disability. Thus, for slight injuries (a range of 1% to 9% of permanent disability), an initial amount of 25% of former “moral damages” is added to the former “biological damages” with progressive increases from 26% to 50% for more serious to severe injuries (from 10% to 34% of permanent disability) and a fixed increase of 50% for severe to maximal disabilities (from 35% to 100% of permanent disability).

The new tables of 2009, the structure of which is still applied today, consist of a list of average monetary values for standard injuries, i.e. they occur frequently (with respect to anatomical and functional aspects as well as relationships and subjective suffering). These guidelines were issued by the Court of Cassation and based on a need for specific evaluations of individual cases and loss incidents that call for the ascertainment of full and personalised compensation. They also provide for the possibility of customising compensation further by using a percentage increase of the average values. Such personalisation is to be used in cases involving peculiarities that can be evidenced and tested (even presumptively) by the injured party. The Court of Milan Monitoring Centre mentions examples of personalisation, such as an injury to the amateur pianist’s finger or a specific hardship caused by the nature of the injury. Increases due to personalisation are provided for up to 50% for minor injuries (up to 9% of permanent disability), then progressively from 49% to 25% for injuries ranging from 10% to 34% of permanent disability, with a fixed limit of 25% of personalisation for injuries up to 100% (For these last cases of severe injuries, we can also consider that the 2009 tables added, at the beginning, a fixed 50% of the former “moral damages”).

A final and rather important novelty of the 2009 tables, at least for the insurance market, concerns the compensation ranges for fatal injuries. Along with the addition of grandparents as a category of beneficiaries for the death of a grandchild, the minimum and maximum values were raised by around 40%. For example, in the 2008 tables, the median value of compensation payable to parents for the death of a child amounted to EUR 159,564, while the same average reached EUR 225,000 in the 2009 tables.

Impact of the 2009 tables

The 2009 Court of Milan tables had an important impact. Their prompt adaptation after the San Martino rulings caused many other courts to adopt them. Moreover, the Court of Cassation took the historic decision to indicate that the Milan tables were the most compliant with its own ruling No. 12408 of 11 June 2011. Given their widespread use across Italy (by this time, the Milan tables had been adopted by more than 60 trial courts, i.e. about 70% - 80% of the Italian courts), they were deemed to provide for a fair and equal treatment when assessing compensation. This “licence” conferred by the Court of Cassation for a single national table, which has since been confirmed by the same court on several occasions, highlights the importance of this tool. Given the failure of the Italian Government to compile a table for damages between 10% and 100% of permanent disability, the Milan tables are currently used in all compensation claims in every sector or business – except for liability claims after a road traffic accident and medical malpractice claims involving injuries between 1% and 10%, where a table is applied that was designed in compliance with Article 139 of the Italian Insurance Code and is updated annually. According to this table injuries between 1% and 10% are settled at amounts significantly lower than those obtained using the Court of Milan tables.

Over the last few years, the government made several attempts to issue the table referred to in Article 138 of the Italian Insurance Code for permanent disabilities between 10% and 100%. Several drafts were discussed, but none of these led to a final approval. Recently, the 2017 Competition Law (No. 124/2017) provided for issuing such a table, explaining that it must be exhaustive with respect to non-economic damages and should provide further regulations that suggest a certain overlap with the Milan tables. For this reason, as many argue, the Article 138 table might amount to a legal ratification of the current Court of Milan tables. To date, however, nothing has been approved and the Milan tables are still an indispensable tool for insurers when paying, for example, more than EUR 4.6 billion for fatal injuries and permanent disabilities of more than 9% of permanent disability in motor third-party liability, which represents 42% of all the amounts compensated in 2016.

2018 edition and adjustments needed

It is quite evident that the popularity of the Milan tables indicates both an acceptance of the limits on payments and the likelihood they will not be replaced.

On the other hand, the 2018 edition of the tables, at least for bodily injuries, clearly reflects the need to maintain current assumptions, mechanisms and values that were identified by the Court of Cassation at the level of “national parameters”. The only change it made to point values was an adjustment (1.2%) as a result of the increase in the consumer price index reported by the Italian National Institute of Statistics. Clearly, some adjustments regarding the correct application of the tables may be needed; for example, certain values can and perhaps should be raised in cases of intentional injury, as mentioned in the introduction to the 2018 edition. This edition also speculates that in practice it is always possible to go below the standardised minimum values if the facts of a specific case justify such a decision. With respect to damages due to loss of family relationship in particular, the judge is entitled to award compensation – even to individuals other than those listed in the tables, provided that evidence is put forward of an intense emotional bond and real upheaval in the life of the surviving relative following the death of a relative (and the same also applies to the case of serious injury to health). It is also stressed, however, that there is no guaranteed minimum to be paid in any case: the judge must carry out an assessment on a case-by-case basis, and the party is subject to the burden of proofing the non-economic damage suffered.

Notwithstanding the aforementioned adjustments needed, the Court of Milan Monitoring Centre made a strong and clear effort to maintain the tables as a tool in development, always considering the possibility of key changes in case law – a dynamic that has contributed to the success of the Milan tables over the years. In the report on the 2018 edition of the tables, reference is made to the monitoring centre’s attempts to collaborate with observers from other courts in order to solve or at least systematically address other issues of interest to the trial courts as well as the legal system as a whole – even if these issues cover other areas than the two main ones that the tables have historically addressed.

In this context, the 2018 edition also addresses compensation for premature death – i.e. when a person suffers from a certain disability as a result of an injury and dies due to an independent event before compensation is paid for the original injury – and for damages that are considered catastrophic where death did not immediately follow an injury, but occurred after a significant amount of time.

For both of these circumstances, which are deemed to be compensation events according to our courts and case law, even if the methods and calculations involved are sometimes very different, the Court of Milan Monitoring Centre has adopted a commendable pragmatic approach. The Court aims to draw perimeters of certainty around standard circumstances, thus attempting a synthesis by drafting two separate tables that should make it possible to manage most events that fall under the case categories outlined above.

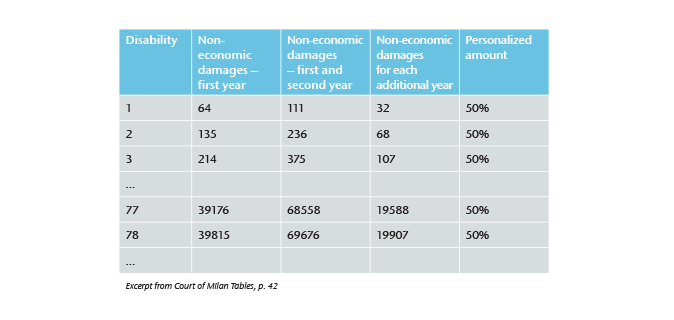

With respect to the loss in the case of premature death, and considering that our legal system provides for compensation with a view to evaluation of the damages and reintegration of the injured individual rather than punishing an injured tortfeasor, the new table provides for a reduction of the standardised compensation in such cases. According to the logic of the monitoring centre, if the table values differ for the same injury due to the age and varying life expectancy of the injured person, it follows that if a victim dies before settlement of the biological damages, the probability assessment related to the life expectancy of the injured person must be replaced by the actual damages caused.

Based on this logic, and in an attempt to standardise the approach to this topic, the Court of Milan developed a calculation method for the 2018 edition whose starting point is a list of values that represent an average annual compensation in relation to the percentage of the permanent disability, regardless of age. For these cases, a table was designed that covers percentage of permanent disability, compensation in the first year, compensation in the second year, compensation in each additional year and a potential personalised percentage increase.

As mentioned, this structure was a new development compared to previous editions of the Milan tables. This is in line with the overall tabular method, which provides for the possibility of adjusting the compensation to the particular circumstances of an individual case, by including an option to increase the compensation by up to 50% to accommodate the individual details of the case. Such details might cover the age of the injured person, which is otherwise taken into consideration only to provide an average value and not to assess individual cases.

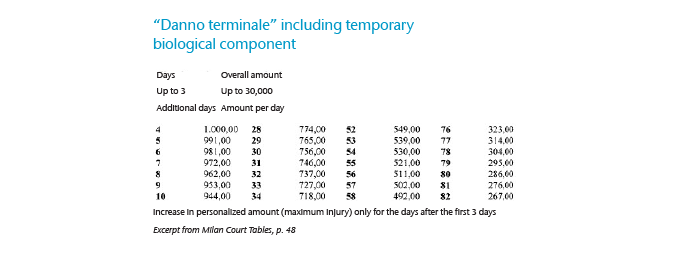

With respect to “danno terminale”1, the Monitoring Centre was correct to identify compensation anarchy in the legal system. Therefore, the first step was an attempt to codify the terminology used to describe phenomena that were often the same. It therefore stated that individuals falling into the all-inclusive category of terminal biological damages would be compensated for all biological damages as well as any suffering linked to the perception of imminent death (including terminal biological damage, conscious agony and terminal moral damage).

When proposing a unified, standardised approach to this aspect of compensation, the Court of Milan Monitoring Centre began by setting out some markers. It expressly states that the victim’s awareness of the end of life is a necessary prerequisite for compensation for terminal damage, which cannot be said to exist, for example, when the victim is unconscious throughout the period leading up to death. The Monitoring Centre also pointed out that compensation is not automatically due beyond a certain period of time between injury and death. It also established 100 days as the limit, meaning the victim suffers by consciously processing and contemplating imminent death and dies within 100 days. After that period, other compensable items like temporary biological damages apply.

In the light of these considerations, the Court of Milan Monitoring Centre now proposes a reference table, which has already been applied occasionally by some courts in other districts. According to the outcomes of those courts, the upper limit for compensation is EUR 30,000 in cases where the victim is in a state of what might be called conscious survival for the first three days after the injury. For additional days, there is a grid of daily values that decreases until reaching the specified value for temporary biological damage on the 100th day. From the fourth to the 100th day, the value decreases from EUR 1,000 to EUR 98, which corresponds to the daily amount for temporary incapacity. In this case, it is also possible to adapt the daily values within a limit of 50% of the amount, depending on the individual’s circumstances, with the exception of the first three days, which allows judges to occasionally adapt compensation to suit specific cases. According to our calculations, the maximum amount of compensation due in line with the criteria set out in the 2018 Milan tables for this specific damage item can reach approximately EUR 110,000, including the maximum possible personalised sum.

The 2018 edition of the tables released by the Court of Milan also contains two other documents with guidelines that intend to promote consistency in compensation for defamation damages by the press and for reckless litigation pursuant to Article 96, para. 3 of the Italian Code of Civil Procedure.

Both documents were analysed, mainly from a case law perspective and based on a scrutiny of the relevant judgements passed by the Court of Milan and other courts (about 90 on each of these issues). As a result of this analysis, a proposal was made for five levels of compensation for the first type of damages. They are to be applied according to the seriousness of the offence, whereby the most serious cases are compensated for more than EUR 50,000.

For damages from reckless litigation, however, the proposal is to award compensation in relation to the legal expenses paid by the defendant in court with the option of increasing or decreasing this figure by 50% depending on the abuse of legal rights by the unsuccessful party.

Conclusion

The 2018 edition of the Court of Milan tables adds new parameters to four areas: compensation for (1) premature death, (2) “danno terminale”; (3) defamation damage by the press and (4) reckless litigation. Surely these most recent four attempts to provide judges – all judges at the Court of Milan, as well as with judges of other courts – with common approaches to compensation for other forms of damage can only be appreciated by the legal (and insurance) community that deals with these issues. The parameters and references for the predictability and uniformity of compensation are an indispensable prerequisite when it comes to containing litigation with only a few residual circumstances that are not covered by them.

On the other hand, even if the tables relating to bodily and fatal injuries have the seal of approval issued by the Court of Cassation in its ruling No. 12408 of 2011 (and subsequent case law), there have been other proposals regarding parameters for compensation, though they have not been confirmed to date by the higher courts. It remains to be seen what will happen on this front, although it should be clear that the prestige earned by the Court of Milan over the years will lead many courts to adhere to the principles and proposals of the Milan tables – not least because, as we have seen for tables relating to bodily injury, it is in the interest of judicial bodies to decrease the volume and increase the speed of litigation in our courts. This workload represents one of the main problems of our judicial system.

We believe that for the insurance and reinsurance industry, the “tabular method” represents a rational approach towards bodily injury compensation. The current system allows assessment of the potential ultimate cost of a claim in a reliable range where the predicted payments are usually confirmed. Of course it looks quite strange that such a relevant aspect for the insurance industry is not regulated by a specific law but by the tables. In this context, it is important to know that the Court of Milan Monitoring Centre does not have the legal authority to impose the use of its tables on judges or courts (even if our main civil court sustained the tables’ authority). Therefore the intervention of our legislature is expected in order to add more stability and rationality to our compensation system where a few items seem to receive higher compensation than in other European countries, which in turn is reflected in the rates on the primary market.

Endnote

- “Danno terminale” is a type of damage that is awarded as a compensation for the suffering of the victim from the point in time when the injuries occurred and the resulting death.