-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

Engineered Stone – A Real Emergence of Silicosis

Publication

Use of Artificial Intelligence in Fire Protection and Property Insurance – Opportunities and Challenges

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance

Publication

Public Administrations’ Liability – Jurisprudential Evolution, Insurance Implications, and a Comparative Analysis Across Countries

Publication

Risk Management Review 2025

Publication

Who’s Really Behind That Lawsuit? – Claims Handling Challenges From Third-Party Litigation Funding -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

AI Agent Potential – How Orchestration and Contextual Foundations Can Reshape (Re)Insurance Workflows

Publication

Diabetes and Critical Illness Insurance – Bridging the Protection Gap

Publication

Group Medical EOI Underwriting – Snapshot of U.S. Benchmark Survey

Publication

Why HIV Progress Matters

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

The 2019 Rome Court Tables – A “New” Threat in Italian Courts?

December 16, 2020

Lorenzo Vismara

Region: Italy

English

Italiano

With large parts of Italy back in lockdown due to a second wave of COVID‑19, the insurance market is still waiting for potential legal actions to emerge from those seeking compensation for negligent conduct during this exceptional catastrophe.

Such cases will have many difficulties to overcome – mainly regarding the burden of proof and the chain of causation elements – before damages are awarded. In Italy, if these lawsuits are successful, all damages relating to bodily injuries are evaluated using tables issued by the courts. The most widely used are the Milan Court Tables and we described their application in a recent article.1 This article provides an overview of the latest version of the Rome Court Tables and considers potential implications for insurers if their use was to be adopted more widely.

In Italy, compensation tables are the recognised method for predicting the amount of bodily injury compensation that should be awarded to victims. With specific regard to MTPL and, more recently, to medical malpractice losses, the Italian Insurance Code provides that non-economic damages should be awarded based on Art. 138 of the Italian Insurance Code for severe bodily injuries (when the permanent disability is above 9%), and Art. 139 for minor bodily injuries (equal or below 9%).

For minor injuries, a set of standard tables has been issued and approved by the Italian Government for nation-wide use. However, an equivalent set of “approved” tables for severe bodily injuries still does not exist. In the previous article, we discussed how this lack of legislation led local courts to draft their own compensation tables in the early 90s, and the chain of events that led the Italian Supreme Court (Corte di Cassazione) to endorse Milan’s tables “the ones to be adopted in order to have fair and consistent verdicts over all of the Italian territory”, in 2011 (judgment 12408/2011).

The “Milan tables” are now used as standard in almost all of Italy’s courts. Only the courts of Venice and Rome didn’t adopt them following the Supreme Court’s statement. The Court of Rome has especially resisted their use and every year issues an updated version of its own tables which are applied to local proceedings. However, it’s interesting that, in the case of an appeal, the vast majority of these first-round verdicts are subsequently overturned. Toward the end of 2018, Rome issued the first draft of an update to its tables, followed by a new version on 25 June 2019.

Given the importance of the Milan tables, we have been closely monitoring their use since 2011. While their introduction was warmly welcomed for the consistency and predictability they brought to bodily injury cases across Italy, over time the Supreme Court has issued several judgements revealing limitations with the current system.2 This growing sense of dissatisfaction is also supported by some Italian doctrine, which points to some items of compensation, particularly around “moral damages”, being too restrictive and standardized to achieve full and satisfactory compensation for some victims.

The latest version of the Rome tables seems to at least attempt to address many of the frustrations with the current system, giving greater relevance to moral damages and providing scope for judges to customize outcomes based on the particularities of individual cases.

What if Rome’s tables were adopted in place of Milan’s?

Regarding the potential impact that could stem from Rome’s tables being adopted in place of Milan’s, it is quite clear that there could be an increase in the level of compensation awarded for severe bodily injuries, plus an additional risk of a decrease in out-of-court-settlements (given the new-found power placed in the hands of judges and final case evaluations becoming less predictable). Below, we compare various aspects of the Rome tables (June 2019) with those of Milan (2018).

Figure 1 describes a severe injury case (a 41‑year‑old victim, suffering permanent damage equal to 90%) and gives an estimation of the same injuries evaluated with the “minimum” available in each court. For Milan, the value previewed in the tables already includes the former “biological” and “moral” damages with no further customization; while the minimum value for Rome also considers the lowest range of “moral” damage (already included in Milan’s case).

Figure 2 shows an estimation based on what we “could expect” in similar cases. This means, in Milan, in addition to the tabled values, a further customization with an amount equal to 50% of the previewed range, and in Rome, the “moral damage” evaluated in terms of 50% of the previewed range. It’s worth mentioning that the “customization” under the Milan court’s system is compensated in few cases and the Supreme Court clearly limited the option to customize compensation to cases where the injury has a severe and/or particular impact on the life of the victim.

A surprising aspect reflected in both figures 1 and 2 is that the previous edition of Rome’s tables was already “more expensive” than Milan’s. This suggests that the judges entrusted with reshaping the Rome tables changed the “curve” underpinning the table to follow the principles laid out by the Insurance Code (Art. 138), as well as recent jurisprudential evolution.

It’s also important to note that, for the first time in the Italian compensation system, the 2019 Rome tables have criteria to evaluate “non-economic” damages suffered by relatives in cases of severe bodily injuries (so-called reflex damages). The same approach is used for fatal injury compensation. The tables show several “requirements” to be fulfilled by the victim and the relative (e.g., age, degree of relationship), assigning points for each level. The sum of the calculated points is multiplied by the value of the point (EUR 6,000 for damages suffered by relatives of a seriously injured person).

With specific regard to reflex damages in favor of the relatives, the complex points evaluation set out by the Rome tables actually leads to lower compensation values than those of Milan (which uses the same range of compensation applied in the case of fatality claims). In fact, comparing the tables on reflex damages, we estimate that the application of the Milan tables in such cases could be around 20% more expensive. For example, the reflex damage suffered by the parents of a seriously injured 17‑year‑old girl would, in Rome, reach a total compensation of around EUR 238,000. In Milan, the same case could provide compensation up to EUR 250,000/EUR 300,000, for each parent.

How do the tables compare on fatal injuries?

With regards to the compensation of fatal injuries, the 2019 update of the Rome tables didn’t bring any significant change, apart from an increase in the value of a “point” (in line with CPI inflation) to EUR 9,806. As explained, the system is points-based and looks at various aspects of the victim and his/her heirs (e.g., in the case of a survived parent, 20 points relate to the degree of relationship). Milan’s tables have the advantage that, because they are in constant use, they are seldomly the cause of disputes with plaintiffs, because both parties know which compensation could be granted by a judge in a specific case.

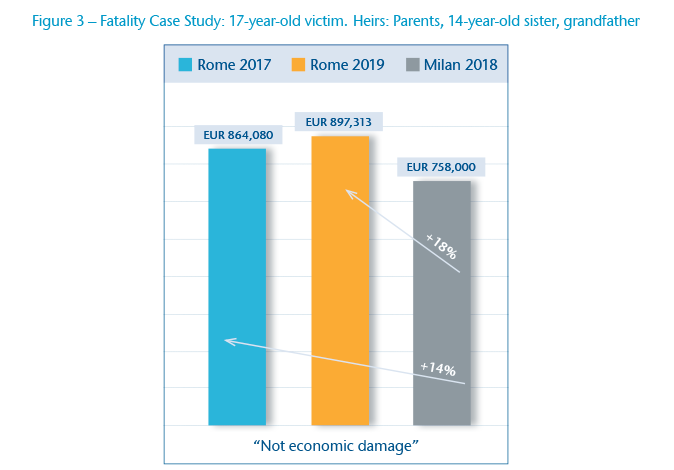

Figure 3 describes a fatal case involving a 17‑year‑old victim with two parents, a sister and a grandfather claiming for compensation. The picture is quite clear. As mentioned before, historically, Rome has been more “generous” than Milan in the case of aggravating circumstances. It’s also important to note that Rome’s points system also mentions cousins, uncles and aunts, who currently have no entitlement under the Milan tables.

As mentioned, Milan’s tables are currently used in the vast majority of Italy’s courts. However, it’s difficult to ignore the doubt being cast by the Supreme Court on whether the current system is up to scratch.

Noting the above scenarios, the institution entrusted with updating the Milan tables has already collected some ideas to change the structure of the system to bring it in line with the latest judicial developments. Many observers believe that after ten years, another relevant verdict from the Corte di Cassazione – like in the 26972/2008 case – could bring some stability back to the system.

What could this mean for insurers?

Despite some points of frustration with the current system, we think it would be quite difficult for the Rome court tables to hold the same role that the Milan court tables have held since 2009. This could only happen if the Supreme Court (in its whole composition) overturns verdict 12408/2011. However, it’s not unthinkable that the Supreme Court could declare the Rome tables to be on an equal footing with Milan’s. This would give judges the freedom to choose the ones that they think best apply in each case.

It goes without saying that there are important implications for insurers, should this happen. The wider application of the Rome tables could significantly increase the costs of claims involving severe bodily injuries and fatalities. On the other hand, the costs involved in compensating victims with less severe injuries (up to around 40% of personal damage), could decrease.

If the Rome tables were to be applied more often and on a national basis, a potential further consequence that shouldn’t be underestimated is a significant increase in the number of cases being brought before the courts. Unlike the Milan tables which have been used repeatedly in the courts for 15 years already, Rome’s are yet to be thoroughly tested through concrete application in litigation cases. The higher levels of uncertainty could make it more difficult for out of court settlements to be reached, with negative implications for all parties involved in this delicate area, not least the victims.

Endnotes

- Lorenzo, The Court of Milan Tables – Bodily Injury Compensation in Italy, https://www.genre.com/knowledge/2018/july/publications/cfpc1807-en.

- Rulings nr. 901/2018 and 7513/2018.