-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

PFAS – Rougher Waters Ahead?

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

Did you Know? A Brief Reflection on La Niña and El Niño

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance

Publication

Pedestrian Fatalities Are on the Rise. How Do We Fix That? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

When Actuaries Meet Claims Managers – Data-Driven Disability Claims Review

Publication

Chronic Pain and the Role of Insurers – A Multifactorial Perspective on Causes, Therapies and Prognosis

Publication

Fasting – A Tradition Across Civilizations

Publication

Alzheimer’s Disease Overview – Detection and New Treatments

Publication

Simplicity, Interpretability, and Effective Variable Selection with LASSO Regression Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Defective Medical Devices – How New European Legislation is Shaping German Liability Laws

July 25, 2019

Martin Peiffer

Region: Europe

English

Deutsch

The influence of European law on national liability law in Germany is often overlooked, or at least underestimated. Liability for medical devices is a good example of this. In recent years, European legislation in the form of directives, regulations, and judgements from the European Court of Justice (ECJ) has fundamentally altered the rules on liability for medical devices in Germany.

Medical devices have been the source of numerous scandals over the past decade. Almost no other field has received as much media attention. From breast implants filled with industrial silicone1 to degrading metal-on-metal hip implants and pelvic mesh implants that erode, substandard medical devices have hit the headlines time and time again. The recall of over 150,000 malfunctioning pacemakers in 2012 is yet another case in point.2,3

Following the constant criticism levelled at the conformity assessment procedure for the use of medical devices regulated by the Medical Device Directive (MDD),4 the EU has taken steps to revise the procedure, re-launching it as the Medical Device Regulation (MDR)5 in 2017. The Regulation will finally come into effect on 26 May 2020.

Although little attention was paid to it at first, in late 2018 the Regulation became the focus of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), an entity that has reported extensively on defective medical devices in the past.6 Their reports led to an enquiry in the German Bundestag.7

The changes and controversy provide good reason to review the situation: what is the current conformity assessment procedure for medical devices (under the MDD)? What influence do European legislative and judicial measures have on German medical device liability law? What changes will the new MDR bring? And, will it be capable of incorporating future developments in medical equipment?

It’s worth noting that, while the focus of this article is Europe, defective medical devices are far from being a solely European issue. To put the scale into perspective, in the U.S., 32 million medical devices are in use, meaning 1 in 10 Americans are currently fitted with one. The United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) clearance process has many similarities to its European counterpart and is also under scrutiny.

The current conformity assessment procedure (under the MDD)

Pursuant to Article 17 (1) MDD, all medical devices must bear the CE mark of conformity when placed on the market.8 This marking aims to ensure, and communicate, that the device doesn’t pose a risk to the health of a patient.9 In order to obtain a CE mark, especially in the case of implants10, a conformity assessment in accordance with Article 11 MDD is required followed by a declaration of conformity, pursuant to Annex II of the MDD11.

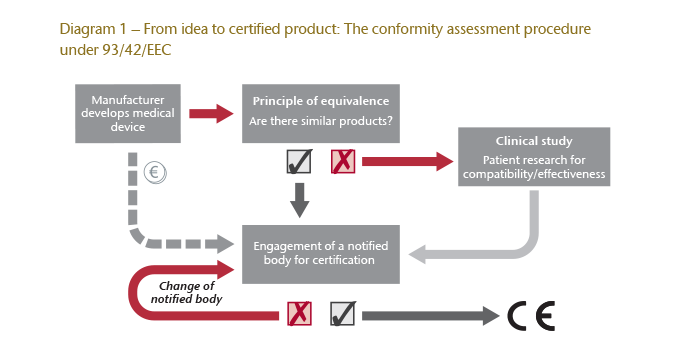

The procedure is carried out by what are known as “notified bodies”, in accordance with Article 16 MDD.12 The manufacturer must conduct a clinical evaluation defined by Annex X of the MDD, to prove that their medical device poses no health risk. To do this, the manufacturer either carries out a clinical study or proves that there is already a similar certified product on the market.13 This principle of equivalence, which deems a scientific appraisal enough to prove comparability, is a key part of the criticism directed at the existing regulations. In simple terms, it means that the conformity assessment will only be based on the information provided by the appraisal.

Diagram 1 illustrates the stages of the current procedure.

Another criticism of the existing (MDD) procedure is that notified bodies are paid by the device manufacturer, thereby providing them with an economic interest in certifying the product in favour of their customer. Additionally, if a notified body doesn’t issue a certification, manufacturers can turn to another body as often as necessary until certification is achieved.

It’s worth pointing out that under the MDD the responsibilities of the notified bodies do not make them regulatory agencies. Rather, their relationship to the manufacturer is exclusively private and they merely act as a partner or attendant in the certification process. The national regulatory authorities are responsible for preventing manufacturers from deliberately circumventing the statutory regulations.14

A CE mark has intrinsically come to represent that a product has been ‘put through its paces’. However, the reality is that many products with the marking have not actually been tested thoroughly, even in the case of sensitive medical devices.

It was the case of the industrial silicone-filled breast implants mentioned above (with over 400,000 potential claimants worldwide) that finally led to the system being questioned. Although a declaration of conformity was issued in line with the rules, countless lawsuits from injured parties were filed against the notifying body, largely because the manufacturer responsible for the crime had insufficient liability cover.15

The effects of European legislation on medical device liability in Germany

Generally speaking, in Germany liability for medical devices is based on the principles of product liability in Section 823 of the German Civil Code (BGB) as well as the German Product Liability Act (ProdHaftG).16

Whereas product liability represents strict liability, tort liability on the part of the manufacturer generally requires the opposing party to be culpable. The difference in the manufacturer’s liability introduced by the litigation is the switch in the burden of proof. Since an injured party typically has little insight into the manufacturing of a product, presenting and supporting a claim is usually very difficult. Therefore, the defending party must instead prove that it was not culpable, i.e. that it did not breach a duty of care.

The manufacturer is subject to a duty of care because the entity that manufactures and markets a product is creating a source of danger. Additionally, the manufacturer must prove that none of its associates have breached a duty of care per Section 31 BGB. However, it is up to the injured party to prove that the product is defective.17 In this context, the definition of a defect in the German Product Liability Act is identical to the definition of a defect in connection with the manufacturer’s liability.18

Influence of directives and regulations

The influence of European legal standards on the design of the German Product Liability Act cannot be underestimated. The Act implements the regulations of the Product Liability Directive19. Additionally, the Medical Device Regulation20 (described in more detail below) creates independent legal grounds for a claim. Article 10 (16) of the MDR states:

“Natural or legal persons may claim compensation for damage caused by a defective device in accordance with applicable Union and national law.”

There was no such regulation in the Medical Device Directive.21

The European regulation has also enlarged the group of targets for claims for damages in this legal field. Besides the ‘usual’ potentially liable parties under the German Product Liability Act, namely the manufacturer/supplier and the importer, the notified body can also now potentially be held liable under the narrow criteria described.22 In the future, it will even be possible to sue the authorised representative of the manufacturer.23

Influence of the case law of the European Court of Justice

Due to the significant influence of European regulations and directives, the preliminary ruling of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in the case of the silicone implants is not unique. Another example is the well-known case involving a health insurance fund that demanded a pacemaker manufacturer cover both the costs of fitting the original devices and the costs of the operations required to replace them, after the manufacturer disclosed that they could fail without warning.24

Even in this case, the German Federal Court of Justice initially suspended the proceedings and took the matter to the ECJ so the definition of defects in Article 6 of the Product Liability Directive25 could be clarified regarding medical devices.26 According to that provision, a product is defective “when it does not provide the safety which a person is entitled to expect, taking all circumstances into account”.

The question in this specific case was whether a medical device that has been implanted into a human body is already defective if products from the same product group are at a noticeably higher risk of failure, even though no defect has been detected in the implanted device. And, if the costs of the surgery to remove the original device and implant a new pacemaker represent damages from a personal injury?

The ECJ answered these questions with the view that the safety requirements that apply to medical devices are of exceptionally high importance and that the directive should be interpreted so that a medical device belonging to a group or series in which a potential defect has been identified can be categorised as defective without having to identify the defect in the product in question.27 The definition of damage in line 1a of Article 9 of the directive is also to be interpreted broadly and encompasses “all that is necessary to eliminate harmful consequences… inter alia, the costs relating to the replacement of the defective product”.

Therefore, with regard to liability for medical devices, even the risk of a defect can be enough to cause product liability. Whether or not the device is actually defective is irrelevant.

However, a judgement by the Federal Court of Justice on 16 December 2008 might represent one possible limit on the obligation to pay damages.28 In the case, a health insurance fund purchased electric adjustable nursing beds which were a fire hazard because the mechanism was not moisture-proof. Although the manufacturer quoted DEM 350 to DEM 400 (approximately EUR 200) for a retrofit kit for each bed, including installation, the health insurance fund demanded that the installation be free of charge.

The Federal Court of Justice ruled that the manufacturer was not obliged to do so unless under certain circumstances, namely when there was a specific danger to the legal interests protected by Section 823 (1) BGB.29 On the other hand, if other – less extensive – measures are sufficient to avert the danger30, the manufacturer is not obliged to provide a non-defective product.31

To put it simply, as long as there is no danger to life without the replacement and non-use alone is enough to avert the danger, the manufacturer is not obliged to provide repairs or subsequent installation under the German Product Liability Act.

The revised Regulation and its consequences

As stated, the Medical Device Regulation aims to improve and reform both an insufficient liability situation and the conformity assessment procedure. But does it?

The new conformity assessment procedure under the MDR

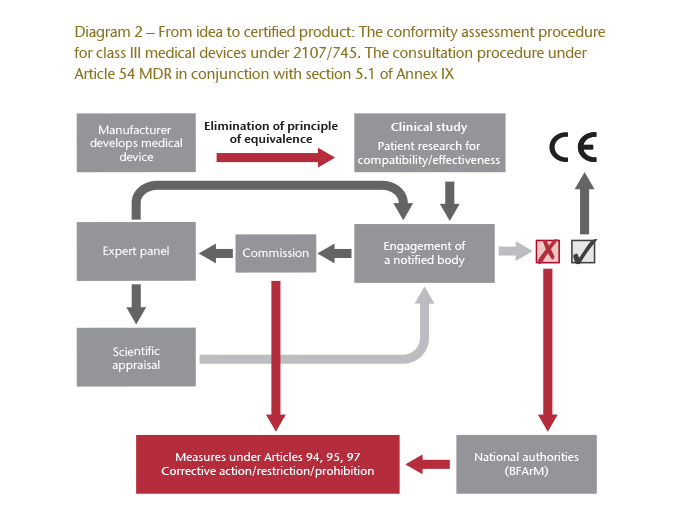

The MDR introduces a new consultation procedure, also referred to as scrutiny (Article 54 ff. MDR). As before, notified bodies will be partners in the certification process, but they are now required to give the clinical study assessment carried out by the manufacturer to the European Commission. The Commission will then consult a panel of experts which will examine the study and the assessment as part of a scientific appraisal. If the outcome of the appraisal is positive, the notified body can issue the declaration of conformity. Otherwise, it is responsible for taking corrective action. A negative assessment can also lead to the restriction, or even prohibition, of licensing instead of corrective action.32

The MDR also contains new regulations for market surveillance with shorter notification periods. The requirements that apply to quality management systems and technical documentation have also been made stricter.

However, what is most significant is that the new consultation procedure virtually eliminates the previously controversial principle of equivalence used in conformity assessment. Now, a manufacturer is almost always required to submit its own clinical study. Equivalence can only be considered if a manufacturer is able to reference comparative raw data from a consenting competitor to prove the similarity of the new device that is in need of a licence. As such, clinical studies will essentially be obligatory for implants and class III devices.

Diagram 2 illustrates the significantly more complex conformity assessment procedure for class III devices under Article 54 ff. MDR in conjunction with section 5.1 of Annex IX to the Medical Device Regulation.

Changes to liability under the Medical Device Regulation

The MDR also specifies and expands the liability scenarios:

Liability of the notified body

The duties of the notified bodies in the certification process are outlined in Annex IX (section 3.4) of the MDR. One new duty, in particular, is performing unannounced audits of the manufacturer at least once every five years including testing a sample of the certified devices at random, regardless of suspicion. In the future, the following criteria must always be examined due to the aforementioned33 standalone grounds for a claim in Article 10 (16) MDR, before the liability of the notified body can be confirmed:

- Are there solid indications that a device does not meet the requirements of the MDR?

- Is there a risk of disproportionate surveillance?

- Would an omitted action be the cause of the damage?

Even if the manufacturer remains responsible for its device and the notified bodies remain mere partners in the conformity assessment procedure, this expansion of duties is prudent because it contractually regulates the distribution of internal liability, at least with regard to indemnification between joint and several debtors.

Liability of the authorised representative

Article 11 of the MDR governs the legal position of the authorised representative34 and his or her liability.35 This is particularly important if the manufacturer does not have a branch in the EU. Without designating an authorised representative, the manufacturer cannot market any medical devices in Europe, pursuant to Article 11 (1) MDR.36 If a manufacturer based outside of the EU infringes its obligations under Article 10 MDR, by designing or manufacturing a defective device, and places a defective device on the market, the authorised representative is liable “on the same basis as, and jointly and severally with, the manufacturer” under Article 11 (5) MDR. Although the authorised representative typically only performs administrative duties, he or she is fully liable for defective devices despite his or her limited legal position. Even terminating his or her mandate does not release the authorised representative from his or her liability (point (h) of Article 11 (3) MDR).

Insurance obligations

Many discussions prior to the announcement of the MDR centred on the introduction of obligatory insurance for the potential targets of lawsuits. However, this is not the case for manufacturers and authorised representatives. The PIP (breast implant) scandal, in particular, has shown the scale that claims for compensation can reach.

Although manufacturers are obliged to provide sufficient financial coverage under subparagraph 2 of Article 10 (16) MDR – an obligation they can satisfy by forming sufficient provisions or having evidence of a liability insurance policy – the Regulation does not contain any similar provisions for authorised representatives.37 Under Chapter 2 (4.3) of Annex XV to the MDR, manufacturers are merely obliged to have evidence of liability insurance cover for damage to participants in the clinical study carried out for the purposes of certification. However, notified bodies are obliged to take out liability insurance under section 1.4 of Annex VII to the MDR.

Evaluation

The conformity assessment procedure under the Medical Device Directive (93/42/EEC) failed to take the growing significance of medical devices into account. Consequently, the new provisions in the Medical Device Regulation (2107/745) are significantly more complex (i.e., the scrutiny mechanism) and encompassing.

The potential liability scenarios have been expanded and made more specific, including the extended obligations of notified bodies and the introduction of liability for authorised representatives. This, of course, also lengthens and increases the cost of the conformity assessment procedure, but consumer protection has no doubt been strengthened as a result.

Overall, both the new Medical Device Regulation and German legislation concerning liability for medical devices are shaped by the fact that the safety requirements for these products are critically important. This is made clear by the broad definition of defects as well as the criterion to define a “danger to life and limb” developed by German case law in connection with liability.

Time will tell if the new regulations are enough to guarantee patient protection. Unanswered questions are already surfacing, such as:

- How does the MDR govern the licensing of 3D-printed medical devices?38

- How are cyber-attacks on medical devices (e.g., those connected to the Internet) to be treated in terms of liability?39

These are just a few of the challenges that the new MDR is already encountering, but have yet to be addressed.

Nevertheless, May 2020 remains the deadline for all existing medical devices to get certified in line with the new MDR rules. But will this even be possible?

The tightening of the laws has prompted the European Commission to inspect all of the test centres (i.e., the notified bodies) currently able to award CE certification. Given that only TÜV Süd in Munich and the BSI Institute in Great Britain have so far been approved, as the German government rather underwhelmingly put it, “bottlenecks cannot – as things stand today – be ruled out.”40