-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

Gen Re’s valuable insights and risk transfer solutions help clients improve their business results. With tailor-made reinsurance programs, clients can achieve their life & health risk management objectives.

UnderwritingTraining & Education

Publication

The Key Elements of Critical Illness Definitions for Mental Health Disorders

Publication

What Are We to Make of Cannabis Use in The Insured Population? Business School

Business School

Publication

Knife or Needle: Will the New Weight Loss Medication Replace Bariatric Surgery?

Publication

Weight Loss Medication of the Future – Will We Soon Live in a Society Without Obesity? Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

All in a Day’s Work – The Hidden Risks in Occupational and Recreational Pursuits

October 02, 2018

Sven Tarnowski

English

Concussions from collisions and twisted ankles, whether the result of one’s own fault or that of a third party, are well-known risks of many pastimes. While the risk of most of those activities are already “priced” in the standard rates of Life and Health insurance products, other activities will receive a percent or per mille loading, based on either their impact on the expected extra mortality or the extra morbidity. By comparison, Income Protection products have a slight twist on the structure compared to life and health products, mostly with regard to claims assessment and claims management; the latter mix Disability risks together with economic risks.

Difference in views

Insurance is, by its nature, a risky business. Thus, it is important for insurance companies to manage their risks properly. The role of underwriting is to control some of the risk at the beginning of the process whereas rigorous claims management ensures that only valid claims get paid at the other end of the process. Both processes are essentially assessing the same risk factors, namely medical, occupational and financial aspects. However, underwriters and claims assessors think differently about biometrical risks and place different values and weights on certain criteria.

One of those differences is how they view and assess risks. Underwriters have by default an ex ante view on pooled risks while claims assessors have an ex-post view on risks that have materialized. While the underwriter compares the imminent risk in standard insurance rates with an individual’s personal risk, the claims assessor has to find the fine line between accepting valid claims and minimizing unnecessary expenses (i. e. the risk of long-lasting annuity claims as well as the detection of fraudulent or uncovered claims). Where underwriting departments have the option to load or exclude above-average risks, claims assessors only see the claims incurred from those underwritten risks. However, the claims assessors are not necessarily aware of the vast number of risks that did not result in claims, despite being underwritten with the same risk factors and thus having the same predisposition of becoming a claim. This naturally leads to the assessors’ exaggerated consciousness of risks although those risks might not appear often in the whole population.

On the other hand, availability bias is important in the daily work of claims specialists. It helps them draw on past claims experience to remember relevant details that might increase the severity and duration of a claim. The different perspective of claims assessors makes them a valuable source of information for both underwriting and research departments, especially when considering adjustments to standard rates and the appropriateness of loadings or exclusions. One area where this is clearly observed is in the approach to hazardous pastimes or occupations.

Availability bias

Availability bias is a human cognitive bias that causes us to overestimate probabilities of events associated with memorable or dramatic occurrences. A cognitive bias is a pattern of deviation in judgment that occurs in particular situations. A cognitive bias can also be explained as a flaw in judgment which is caused by memory, social attribution, and statistical errors.

Standard rates in insurance

A hazardous pastime or occupation can be defined as an activity, undertaken for pleasure or as part of one’s occupation, which is considered to be high risk to one’s health and safety. Typically, the standard rates of an insurance cover incorporate the average number of injuries and deaths, as well as the ordinary accident risks (e. g. car accidents). However, consideration is also given to occupational risk and common pastimes – risks such as sports or travel to foreign countries. Those pastimes can be distinguished in two dimensions:

- The number of people that participate in the pastime (possible frequency of risks)

- The number and nature of possible accidents that can happen during such pastimes or activities (possible severity of risks)

It is clear that if more people start to participate in a sport or activity, the overall number of accidents in this sport or activity should also start to rise. If, for example, a large number of people in the insured population are doing a specific sport or pastime activity and the severity of associated injuries is low, there will not be any loading to the standard insurance rates since the risk is already priced in the population’s overall mortality rate.

A good example is soccer, in which a large number of people participate in the sport and the number of serious injuries is low, so the price (loading) doesn’t increase the price even if one is competing in amateur matches. Other sports that are carried out by fewer people incur a different price that includes a risk premium. For example, people participating in mountain bike races might get an exclusion or a loading on their risk premium appropriate to the calculated extra risk. The same applies for pastimes or occupations that imply an above-average accident risk where the number of injuries is, by nature of the sport or occupation, extremely high.

Distinguishing between products

When considering the potential risk inherent to a particular pastime, it is also important to differentiate between insurance products. Some pastimes are associated with a high mortality rate, but the risk of disability is lower; while others do not significantly increase mortality but are known to have a high incidence of disabling accidents.

From an insurer’s perspective, Income Protection Disability products are unique. Unlike lump sum benefits (death, disability, critical illness) where the total payment is known, an Income Protection claim may result in an unknown number of monthly payments. Typically, the premium that has to be paid for such a product is dependent on the occupational class of the insured. This is, in general, a good approximation for the biometric risk as blue-collar workers have a higher risk of the bodily injury (at their workplace) than white-collar workers. However, it has some problems representing the pastimes risk that is discussed above.

Access to pastimes

In a more general way, one could ask if risky pastimes are really making that much of a difference to overall Disability claims experience. The raw numbers show that only a small fraction of employees have an Income Protection policy, and this fraction includes both the high and the low sums insured; thus, overall it might not be too much of a concern for an insurance company as a whole.

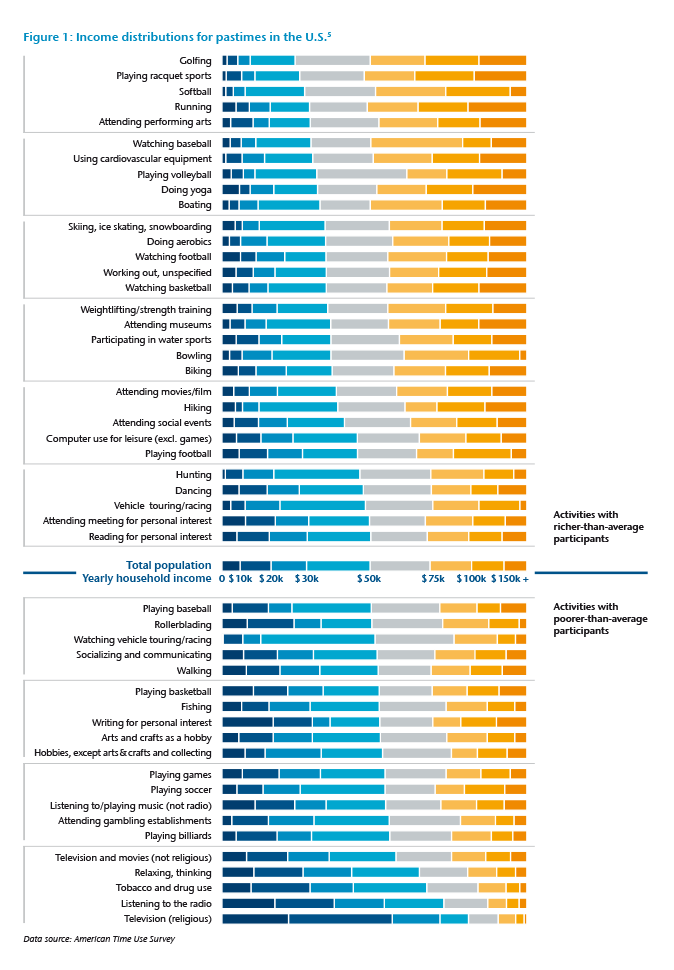

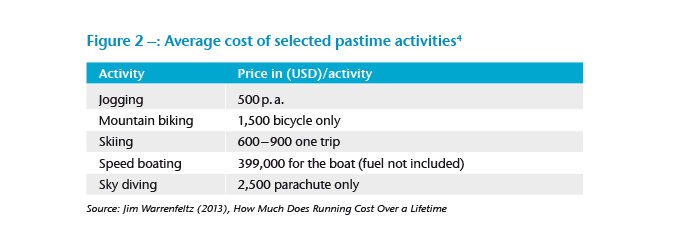

The level of participation in sport and physical recreation differs a lot between the different income groups. According to an Australian/New Zealand study, high income households are more than 50% more likely to participate in sport and physical recreation than low income households.1 Figure 1 shows the distribution of pastimes between the different income classes in the U. S. It shows that different pastime activities differ hugely between the income classes. It also shows higher income classes prefer activities that need expensive equipment or a lot of it (e. g. golfing, racquet sports or biking). People offer different explanations for this. If asked, the second most common reason for not participating in a sports activity is that the activity is “too costly/can’t afford”.2,3 If we break this down even further, we can develop some hypotheses. Figure 2 shows the different costs of selected recreational pursuits. It can easily be seen that for an average household, many sports – independent from the loading – are not affordable.

Comparing people’s participation in the first three pastimes (jogging, mountain biking, skiing) in Figure 2 shows most of the time they will get the same or at least a similar underwriting result. Thus, those pastimes are far from being hazardous, especially when compared with very risky pursuits, such as speed boating or sky diving. The crux is that the activities that can cause severe enough accidents to prevent people from being able to fulfill their occupational duties are most often the ones that are only attainable for insureds who have a higher income. At the underwriting stage, however, as long as the insureds are not competing in any races or increasing their risk in other ways, most pursuits are considered to deserve the same standard rates. This not only holds for annuity payments in Income Protection products but also for Lump Sum Disability Products.

Case study – Slipping dentist

A Disability claim was received from an Income Protection policy for approximately USD 17,200 per month. A 63-year-old self-employed dentist slipped on a boat ramp, resulting in a disc prolapse confirmed by an MRI scan. The policy payment was contractually limited to a maximum of one year. The underwriting was done 27 years before the claim; thus, no enforceable non-disclosure came under discussion. As the dentist disclosed scuba diving as a pastime activity at the underwriting stage, a slip on a boat ramp was within the expected accidents at claims stage. The limitations – after the accident – were left-sided sciatica with extension to the leg. The dentist could not sit comfortably and was limited in his bending ability. After the review of the medical documents and ancillary information, we requested an occupational therapist to perform a functional job description and assist the dentist on his return to work. From the neurological symptoms described in the medical reports, the hope was that the dentist might return to work the following month. Two months later, after the conservative treatment failed, the dentist had a discectomy with a partial laminectomy on the prolapsed disc. Although the goal of the rehabilitation program was to be fully pain-free and to restore function so he could resume his the past role in dentistry, two months after the operation, the dentist’s claim remained valid, and eventually the claim was covered for the maximum time of one year.

Income, sports and insurance risk

In addition to having greater access to high risk pastimes, we have seen that high income occupations are mostly considered as being relatively unrisky, but the thresholds of becoming fit for work again following an injury can be quite high. Thus, even a low number of claims can trigger not only higher but also longer payments. While sport is undoubtedly good for your health and can help to relieve stress, it can also be dangerous to one’s health and safety, causing short to medium periods of absence from work.

In cases where the severity of an accident might be the same for two insureds, one individual’s occupation can mean a significant difference in the sum insured and impact of the injury compared to the other insured. This is especially so with highly educated or specialized occupations. In particular people in certain occupations – such as dentists, surgeons, and most of the occupations that require a license (e. g. pilots) – typically have a high sum of Income Protection, and have an associated high cost to their becoming fit to work again. This gets especially expensive when secondary effects – such as psychiatric problems – arise from the long absence from work.

Furthermore, self-employed or business partners, who work more than 60 hours per week, find it difficult or sometimes impossible to make a gradual, phased (graded) return to work. Although those people tend to have a higher intrinsic motivation, we see no faster return to work compared to other occupations. From our experience, this is mostly because those individuals hold knowledge that is crucial to the operating of the business and thus their positions cannot be shared easily between other employees. Additionally, it may not be feasible to work reduced hours in an early stage of recovery, because the work demands constant contact with one’s working environment and colleagues. Or, in the case of the solo self-employed, reduced hours would not be enough to keep up customer relationships. Although there are multiple ways to assist employees (delegation of work, more flexible work times, etc.), it is not always achievable to get an insured back to work, even with a graded approach.

In the above cases, the level of mental or physical demands can be so high that even a small deficit in ability makes it impossible or unsafe for the claimant to return to work. Furthermore, the occupational duties are so unique that a claimant cannot be easily accommodated in any other suitable occupation and a graded return to work is hardly achievable. Take, for example, a dentist or surgeon, who has to be able to stand and sit for long periods in a crouched position working on a patient with sharp equipment. Even a small finger injury may result in a valid claim. Likewise with other licensed professionals, such as pilots, the smallest impairment can make it unsafe for an individual to perform his or her duties. People in such occupations, in contrast to office-based jobs, are hardly able to return to work without being 100% fit. On the other hand, these jobs are known to represent a good occupational risk class. Combining those high-income risks with the possible severity arising from their favored pastime activities, it is clear that claims assessors should consider possible interventions early in the management of such claims. Suitable methods, such as claims triaging, as well as involvement of an occupational therapist, can help to reduce the exposure of such claims.

Summing it up

Although in general white collar and specialized occupations bear a lower occupational risk than other occupations, and specialized employees are normally more intrinsically motivated to return to work after an accident, both groups bear a higher risk in recreational pursuits that should not be underestimated at underwriting or claims stage.

Several reasons account for this increased risk: One is that people with higher income are more likely to participate in recreational sport and pastimes, and as the nature of sports indicates, an accident is more likely. Another point is that with a higher income the participation in high-risk sports rises; many of those sports require expensive equipment or take place in remote locations that are costly to reach. Accidents that trigger a claim on Disability Income insurance tend to be more severe, and it is hard to help the insured get back to work if he or she is not totally fit again. Those factors increase the amount paid by the insurer, so the value of good claims management in the early stage of such accidents should not be underestimated. Thus, the claims management departments must not only carefully monitor such claims but should also intervene earlier in them to minimize the risk of long-term Income Protection claims.