-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves?

Publication

Pedestrian Fatalities Are on the Rise. How Do We Fix That? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

The Effects of Heatwaves – A Look at Heat-related Mortality in Europe and South Korea

Publication

The Key Elements of Critical Illness Definitions for Mental Health Disorders

Publication

An Overview of Mitral Regurgitation Heart Valve Disorder – and Underwriting Considerations

Publication

Body Mass Index as a Predictor of Cardiovascular Health Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Petrochemical Risks – Why Insurers Must Handle Them with Care

Insuring petrochemical risks presents insurers with a special set of challenges. This article focuses on the downstream sector of petrochemical production and explores what sets these risks apart from “normal” industrial risks.

The chemical industry is the fifth-largest manufacturing sector in the world, directly contributing around USD 1 trillion to global GDP annually and employing 15 million people.1

Petrochemicals are predominantly used to make products that other industries process to manufacture everything from vehicles to flat-screen TVs, packaging, insulation, sun cream, and clothing. As such, the chemical industry is closely linked to almost every other major manufacturing sector.

In the past, large petrochemical facilities have had a history of incurring substantial fire and explosion losses. This is perhaps unsurprising when one considers the complex production processes, drastic reaction conditions, and flammable substances involved, coupled with extremely high-value concentrations.

Interestingly, while losses from material damage can be huge, subsequent losses from business interruption (BI) are on average even bigger. This is especially the case for units which manufacture intermediate products for other production facilities.

Current market conditions

The petrochemicals sector has been a difficult place for insurers for many years. However, the market has shown some signs of recovery in the last few months, with moderate rate increases.

Nevertheless, it remains a tricky market in which to operate. Despite significant losses and poor results, surplus capacity continues to put pressure on prices and prevent rates from recovering. Though we’ve seen some markets withdraw capacity, it has (at least partially) been replaced by new capital.

In 2018, theoretically available downstream market insurance capacities were estimated to be around USD 4 billion in North America, and almost USD 7 billion in International markets.2 However, in reality, this capacity is not always available for individual risks.

In recent years, losses for the downstream sector have almost always exceeded premium income. According to one source, in 2017, global expenses for downstream losses in excess of USD 1 million amounted to over USD 5.5 billion.3 Despite the enormity of these losses, premiums are stagnating at a low level: in 2017 (a year of record losses), the global premium was estimated to be around USD 2.2 billion. While other sources report more optimistic premiums, the figures make it clear that it remains very difficult for insurers to earn money in this segment.

The core question is, how can insurers operate profitably in this highly volatile segment over the medium and long-term?

The downstream sector

In the petrochemical industry, the term “downstream” refers to all stages of production after the crude oil has been transported to the refinery. “Downstream” typically starts in the refinery and encompasses the creation of petrochemical and intermediate products. As mentioned earlier, the different processing units are highly interconnected. One “bottleneck-unit” shutting down can quickly lead to production stalling in others, resulting in significant interdependency or contingency business interruption (CBI) losses.

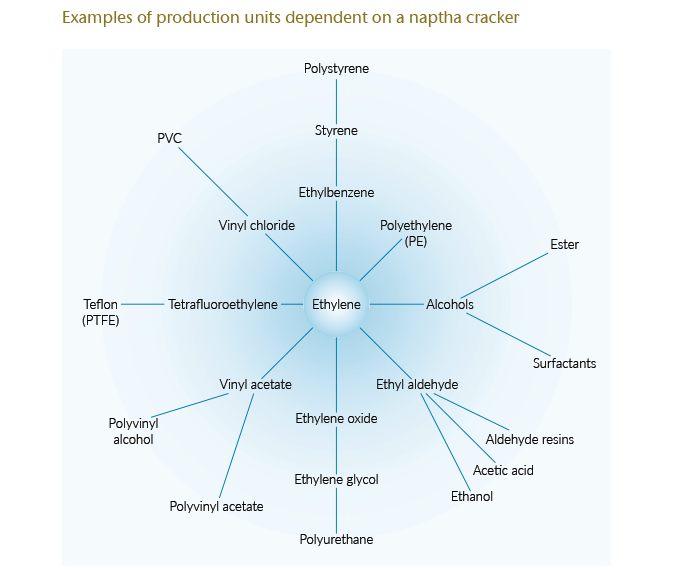

The naptha cracker

The naptha cracker is a good example of such a critical unit. The cracker represents the heart of most large chemical sites and is the start of numerous value chains. In a naphtha cracker, the naphtha distilled from crude oil is broken down (cracked), i.e., the long-chain hydrocarbons are converted into important basic materials such as ethylene and propylene.

The reaction conditions inside the naphtha cracker are extreme. The cracking reaction occurs at high pressure and at temperatures in excess of 800 degrees Celsius. A large cracking plant, including product preparation facilities, can cover tens of thousands of square metres, process around 2,000,000 tonnes of naphtha per year, and be worth several hundred million euros.

Ethylene and propylene are gaseous and highly flammable. Both can form an explosive mixture in the air even at relatively low concentrations. They represent two of the most important molecules in the chemical industry and are important intermediate products for making plastics, paints, solvents, pesticides, vitamins, and many more items.

At large, integrated petrochemical plants, problems with the cracker can have significant knock-on effects with relatively minor failures capable of causing significant BI losses. If the buyers are external customers, potential CBI losses can run into hundreds of millions of euros in some cases. It is therefore vital that insurers understand these interdependencies. Even though CBI losses are often subject to a limit, one unit shutting down can affect multiple customers and suppliers.

Vapour cloud explosions

The term ‘vapour cloud explosion’ (VCE) is of crucial significance to insurers operating in this sector as the event is often considered to be the maximum loss scenario (VCE EML), by which policy limits are defined.

A vapour cloud explosion is the most dangerous, destructive loss event in the petrochemical industry. In principle, all processes involving flammable gases or liquids being heated above their atmospheric-pressure boiling point are potentially at risk of a vapour cloud explosion.

If a leak occurs, flammable gases or vapours can escape into the ambient atmosphere and form explosive mixtures. Even liquids with a high vapour pressure such as gasoline can form an explosive gas cloud if some of the substance is released, e.g., if a tank is overfilled. If an explosive cloud comes into contact with an ignition source, a devastating explosion occurs.

A vapour cloud explosion in a naphtha cracking plant can inflict hundreds of millions of euros worth of property damage alone. If the cracking plant, the heart of the site, remains non-operational for months, other facilities which depend on its products are also unable to operate. As mentioned, BI losses can quickly eclipse those from physical damage in such cases.

One only needs to recall the explosion at the Buncefield oil depot in December 2005 to appreciate how destructive VCEs can be. The blast, which measured 2.4 on the Richter scale, happened when 250,000 litres of petrol leaked from one of the tanks, resulting in a huge vapour cloud which then ignited. It led to what the media described as the worst fire in peacetime Europe, injuring 43 people and destroying multiple homes and businesses in the surrounding area.4

There are various models for calculating the estimated maximum loss caused by a vapour cloud explosion. For all, the outcome depends to some degree on the input parameters. In other words, results can vary even when the same program is used. A lower probability event ultimately causing a larger loss can’t be ruled out.

As the estimated maximum loss caused by a vapour cloud explosion is often used as a guideline for structuring insurance cover and defining limits, insurers must proceed with caution. In worst-case scenarios, mistakes in the estimate can lead to gaps in cover.

A challenge for insurers

To assess the complex risks involved in petrochemical production insurers need comprehensive risk information that can only be prepared by experienced, specially trained experts. Larger international insurance programs often cover numerous locations around the globe, including those with increased exposure to natural hazards.

Underwriters in this segment require a good degree of technical understanding to distil the flood of information and make underwriting and premium decisions based on careful analysis and evaluation of all the facts. It goes without saying that strict guidelines are needed when underwriting petrochemical risks. Important points to consider include:

- Careful calculation of the value of both property and business interruption cover

- Careful accumulation and capacity control

- Clear definition of sub-limits

- Natural hazard exposures and their pricing

- Qualified assessment of the maximum foreseeable loss of a vapour cloud explosion

- Consideration of potential interdependency and contingency business interruption losses

While the high average losses are important to consider, attention must also be paid to the high volatility, especially as a result of large interdependency and CBI losses. Such losses can be particularly hard to assess and are often not factored into VCE loss estimates. Finding reliable figures is a habitual challenge.

Given the complexities, conditions and potential losses involved, insuring petrochemical risks is unlikely to become less challenging anytime soon. In the interim, a clear strategy, disciplined underwriting (based on strict guidelines), careful risk accumulation management, experienced underwriters and risk engineers - and an excellent reinsurance partner – remain key prerequisites for success in this sector.

Our specialist team can help you meet the challenges involved when insuring petrochemical risks. Contact your Gen Re representative or reach out to me directly for details.

Endnotes