-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves?

Publication

Pedestrian Fatalities Are on the Rise. How Do We Fix That? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

The Effects of Heatwaves – A Look at Heat-related Mortality in Europe and South Korea

Publication

The Key Elements of Critical Illness Definitions for Mental Health Disorders

Publication

An Overview of Mitral Regurgitation Heart Valve Disorder – and Underwriting Considerations

Publication

Body Mass Index as a Predictor of Cardiovascular Health Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Challenges in Managing Health Insurance in Asia

July 27, 2017

Irene Ng

Region: Asia

English

Across many Asian markets, health insurance is a popular and highly sought-after product, from the perspective of end consumers as well as insurance providers. An increasing demand for healthcare across Asia stems fundamentally from the steady population growth, escalating medical costs and growth in wealth across Asia, all of which increases the per capita consumption of healthcare services. Health insurance is often regarded as a “door opener” for sales agents, providing an opportunity to make a convincing sale and then to market other higher commission products.

One main reason private health insurance has a strong demand in Asia is due largely to the limited state-funded health insurance support in many Asian countries, or the quality of such state-funded health care is poor, thereby increasing the demand for privately funded/owned health insurance.

Despite the strong demand, this is not a product recommended for all insurance providers' portfolios. Health insurance is easy to sell but exceedingly difficult to manage. Before an insurance company jumps onto the bandwagon to launch a health insurance product, it should be aware of a number of considerations and challenges and consider how it would or could manage the multifaceted risk.

A four-way game

When considering the “players” in a life insurance product, we often see three main parties involved, namely the insurance company, sales agents and the consumer (insured). In a health insurance offering, a fourth party joins this game – the healthcare providers (i. e. hospitals, doctors, surgeons). The insured’s motivation in purchasing a health insurance policy is to have an affordable coverage that pays for comprehensive medical treatment when required. The sales agent wants to earn his commission, whilst the healthcare provider, although with primary objective of treating patients, is also focused on maximising its profits. The insurance company, whilst profit-centric, is essentially interested in providing a viable and sustainable product to the policyholders. Since the interests of each of these parties in the “healthcare game” are not aligned, their opposing forces render the management of a sustainable, affordable and profitable health insurance product a great challenge.

Nevertheless, it is in the interest of all these parties that the levers work in sync; a fall out of one part will render the entire ecosystem unviable. From the insurance provider’s perspective, depending on the type and scope of the health insurance plans it is providing, one of the greatest challenges in maintaining the cost of the healthcare premium lies in its ability to negotiate and control the charges levied by the healthcare providers on its policyholders. Without strong negotiating power, the insurer would very quickly experience rising cost of claims beyond the expected healthcare inflation.

Healthcare inflation

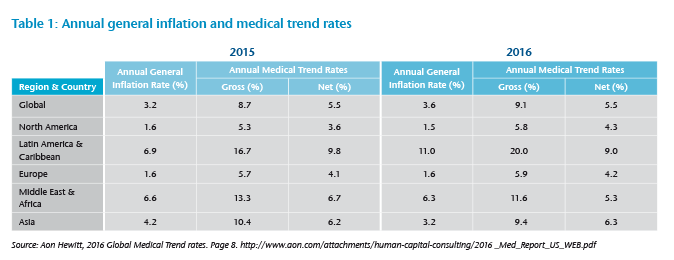

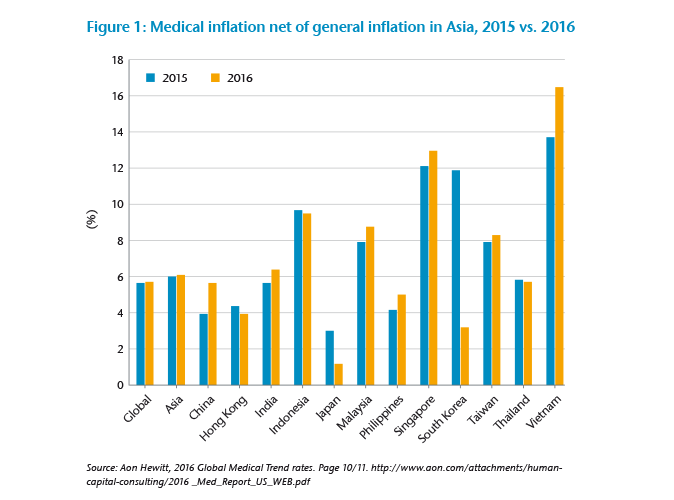

Globally, healthcare inflation typically outstrips local general inflation, often by many folds. Using historical data on medical inflation does not often provide confidence on the future inflation rate. According to a study by Aon Hewitt and reported in the “2016 Global Medical Trend Rates” report, the average global medical inflation rate increased from 8.75% in 2015 to 9.1% in 2016. Asia consistently out-performs the global average at 10.4% in 2015 and 9.4% in 2016. (See Table 1 and Figure 1.)

The cost of medical inflation has to be built into the pricing of a health insurance product. Actuaries consider the number of years of medical inflation to be priced into the premium rates, and this can be a challenging task, as many factors can influence this inflation figure and often make prediction difficult.

Unfortunately, one contributing factor in escalating medical inflation is also fueled by richer, more comprehensive health insurance coverage available in a market, which drives up healthcare utilization. Competition pushes insurers to extend coverage scope such as increasing annual and lifetime limits, sometimes to the extent of removing such limits completely; removal of inner limits (i. e. provide “as charged” coverage, reimburse up to the cost of medical treatment regardless how much doctors or hospital charge), removing co-sharing elements, such as deductible and co-insurance, etc. Experiences have shown that such “limitless” products encourage over-utilisation and over-charging, senseless usage and prescription of medical services, causing a “buffet syndrome” of medical utilisation, leading to worsening experience of such portfolios. A study of the average hospital bill size – a comparison between a portfolio with a deductible and coinsurance feature and a portfolio that pays almost 100% of cost of admission – shows that the medical bill size of the latter group is 20%-25% costlier than the former.1

The intricacy of medical insurance product pricing is one of the factors making a medical portfolio “difficult to manage”. The remaining sections discuss some other trends seen in medical portfolios in Asia and possible measures insurers could consider putting in place to better manage loss ratio and increasing premium charges.

Utilisation trend

Not surprising to see in medical portfolios, we often see higher utilization rate of medical services and facilities as compared to that in the general population. These include longer average length of stay in hospital, frequency of medical consultation/admission, frequency of investigation and number of investigations per diagnosis. The average length of stay is perhaps less of an issue in countries with insufficient supply of hospital beds to meet demands, such as in Singapore, but more of a noticeable issue in countries with greater supply of hospital beds, and disproportionately so in larger cities where the proportion of insured population is also higher.

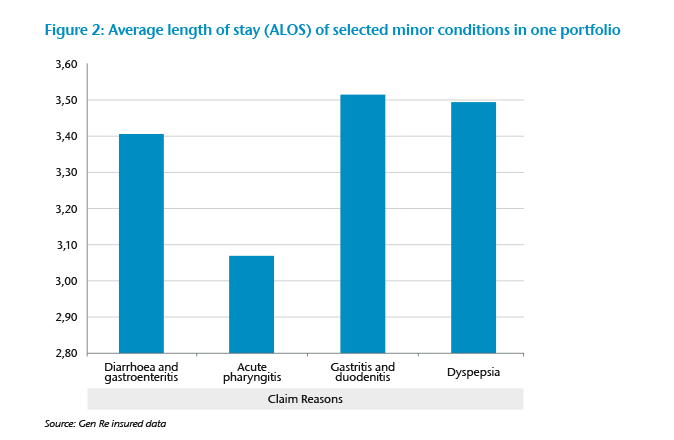

In one health portfolio in Asia, we see that the incidence of admission due to minor acute conditions is much higher than the general population. This is not surprising, as individuals with health insurance would want to maximize the coverage and opt for inpatient rather than outpatient treatment, especially if the insurance provides only inpatient coverage. It is rather shocking to see in one portfolio the maximum number of days of admission for diarrhea and gastroenteritis, both of which are minor conditions which one would even question the need for hospitalization, reached 31 days, and for dyspepsia 18 days. (See Figure 2.)

It is also often experienced that an insured patient utilizes more of the hospital facilities (e. g. investigations, tests, scan, etc.) as compared to an uninsured patient for the same diagnosis. Doctors are often guilty of causing this as they would recommend all tests available, whether necessary or recommended for the medical condition, since the costs will be largely borne by insurance companies. Most patients would not be able to decide whether all these tests and investigations are necessary and would go along with any recommendations from the doctors, always with full confidence that if the doctor recommends it, it must be necessary.

Cost of claim

The average cost of claim is an important determining factor in the cost of the health product. This can differ depending whether the product covers only treatment in specific types of hospitals (e. g. government hospitals vs. private hospitals) and to what extent can an insurer control the charges levied by service providers. In countries with no strict (governmental) control – on charges by hospitals and specialist and doctor consultations, surgeon fees, cost of surgical procedure, or at least a publicized benchmark charges for surgical procedure – we often see that the cost per admission can rise significantly amongst the insured population and the differential can be significant between private and public hospitals. This is seen in Singapore where the average cost of treatment in private hospitals was approximately twice that in public hospitals (without government subsidies) in an industry study on the cost of admission between 2012 and 2014.2

A more significant differential is seen in other Asian markets, especially where there is significant government subsidy for treatment in public hospitals. Holders of private health insurance cover would tend to prefer treatment in private hospitals due to the shorter waiting time and better care, thereby pushing the cost of claim upwards. There is also experience showing that doctors inflate the charges when a patient has comprehensive health insurance, reflecting the mentality that insurance companies will pay for such costs, thereby not hurting their patients financially.

Anti-selection

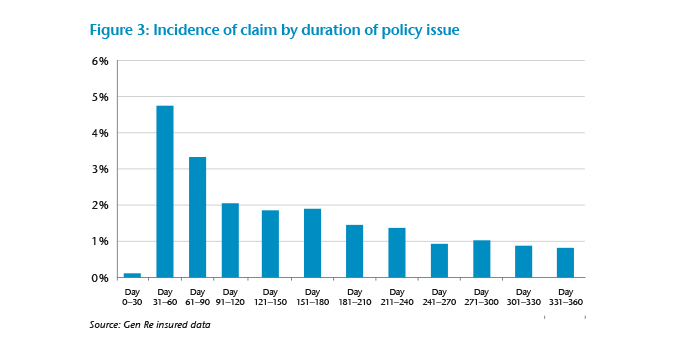

As with any form of insurance, anti-selection is an issue of foremost concern to insurers. This is more apparent for health insurers, as the impact of anti-selection is seen more acutely in health portfolios. Typically in Asia, a health insurance product has a 30- to 90-day waiting period, whereby admission during this period will only be covered if due to accidental causes. It is not uncommon to see that the incidence of claim peaks right after the waiting period before stabilizing to a normal level. This is seen very clearly in one portfolio studied by Gen Re (see Figure 3) where the incidence of claim peaks right after the 30-day waiting period at 4.7% at days 31-60, as compared to less than 1% at 1 year post policy issue. This shows obvious anti-selection, where the insured either has the intention of attaining a hospital consultation prior to policy issue, or waiting out the waiting period before getting treatment so as to be covered under the policy.

Control measures

The challenges to a health insurance portfolio are complex, multifaceted and differing in different markets. The same product could work well in one market but cause significantly high loss ratio in another. Multiple factors can influence the experience of a health portfolio, and not all control measures are equally effective in all markets. Below are some suggested measures that insurers could consider to better manage their health portfolios.

- Structuring their products to encourage better self-management and utilisation of health services

- Establishing inner limits to control unreasonable charges and over-prescription of tests and investigations

- Imposing deductible and/or co-insurance to encourage self-management of hospital services utilization

- Having agreed treatment charges with network hospitals, and encourage insureds to seek treatment in network hospitals

- Setting a longer waiting period for specific minor conditions that can often pre-date policy issue (e. g. sinusitis, hemorrhoids, piles, etc.) but need no urgent treatment

Atop the above specific measures, health insurers need to have a strong claims monitoring mechanism in order to keep abreast of portfolio experience. Early detection of any fraud or abuse is foremost in helping to ensure that illegitimate claims are arrested early. In order to achieve this, data analysis of past experience would help highlight areas where abuse could occur and enable claims assessors to devote more time and resources to investigate suspicious claims. As the volume of health claims are often high on a daily basis, relying only on the human eye and individual claims assessment to detect abuse or fraud is ineffective. However, employing data analytics to study factors contributing to high loss ratio would enable insurers to manage health claims more effectively and efficiently.

Health insurance is a valuable product to consumers and provides much needed protection in times of need for medical care. It is in the interest of all parties in this ecosystem, with the government included, to ensure that health insurance remains affordable and sustainable to all. Careful management of this product is needed and requires strong commitment from the insurers to achieve this.

Endnotes

- Managing the Cost of Health Insurance in Singapore, 13 October 2016, prepared by the Health Insurance Task Force (“HITF”), Singapore.

- Ibid.