-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves?

Publication

Pedestrian Fatalities Are on the Rise. How Do We Fix That? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

The Effects of Heatwaves – A Look at Heat-related Mortality in Europe and South Korea

Publication

The Key Elements of Critical Illness Definitions for Mental Health Disorders

Publication

An Overview of Mitral Regurgitation Heart Valve Disorder – and Underwriting Considerations

Publication

Body Mass Index as a Predictor of Cardiovascular Health Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Suicide – Right To Die, Wrong To Claim?

April 03, 2014

Ross Campbell

English

The concept of suicide has never been a simple one to define. The term encapsulates a wide variety of individual circumstances and moral and religious perspectives, in addition to potentially problematic legal definitions. The insurance industry has been engaged largely through claims with the latter issue, but the rise of two phenomena prompts a re-examination of the industry’s response when someone takes his or her life; one is the rise in assisted suicide; the other is the recent worsening of suicide trends in much of the world – a phenomenon brought about by the worldwide economic crisis.

The relationship between assisted suicide and the law is not a new one. In ancient Greece, those who wished to die by their own hand received official permission – and poison – from authorities only after successfully petitioning magistrates in the senate.

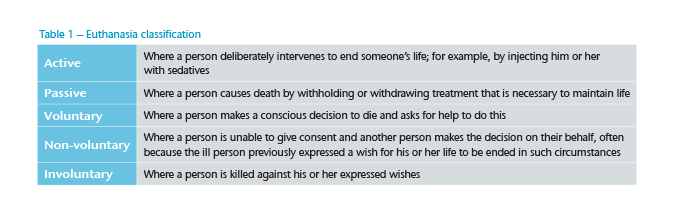

Throughout history, the subject of suicide has sparked debate on legal, ethical, cultural and religious grounds. Euthanasia is a wide term that describes the intentional ending of a person’s life, yet it too has shades of meaning and differing legal definitions depending on context.

Legislation covering assisted suicide and euthanasia varies. In some regions, notably the Middle East, it is prohibited in all forms. In Benelux countries as well as some US states, legal code allows (active) physician-assisted suicide (PAS).2 In Switzerland, where (passive) non-physician-assisted suicide (NPAS) has been legal for over 60 years, any mentally competent person has the right to obtain a lethal substance – which must be taken without external assistance – to end his or her life.

This article considers the role of NPAS within suicide death, and the complex issues that this grey area raises for claims managers.

Assisted death – A moral maze?

If a television documentary depicts an animal dying of thirst on a drought-ravaged savannah, some ask if human help could not have saved the creature. Of course, while difficult to watch, our intervention would work against the natural order of things. Conversely, we operate on a moral obligation to relieve the suffering and respect the dignity of our fellow human beings.

Modern medicine provides effective treatment for conditions that were previously fatal, allowing lives to be prolonged. An unexpected, sometimes unwelcome, outcome is that life is sustained in individuals with physical and mental incapacities that cannot be fixed – people whose irreversible degenerating condition causes them unquenchable pain, discomfort and indignity. While the work of doctors postpones death for many, some hopeless patients desire only a merciful exit from a life they feel has been destroyed by illness and is therefore beyond repair.

Suicide statistics are an indicator of mental health norms, yet some choose suicide for reasons unrelated to any psychiatric condition. For those locked within the terminal stages of a severely disabling disease and suffering a compromised quality of life, assisted suicide is a rational option to avoid prolonged suffering.

The case for assisted suicide appeals powerfully to notions of compassion and self-determination, yet the choice to end a life involves complex moral decisions. A wish to commit suicide by medical means, perhaps on receiving a devastating diagnosis, may be clear when the person voluntarily, and independently, decides to overdose with the intention of dying from it. The wish is much less clear when assistance has been required to complete the task – when the person, while mentally competent, was physically unable to carry out that final wish in a dignified manner without help from others.

There is a tension between a moral right to freely choose self-destruction and the possible end-point for a society that actively supports this behaviour in persons who lack the physical or mental capacity to carry it through without assistance. Van der Maas discussed this tension, asking if accepting a request for assisted suicide from a terminally ill yet mentally competent patient represented a first step toward an unintended and undesirable increase in the number of less careful end-of-life decisions and to gradual social acceptance of suicide that could be assisted for morally unacceptable reasons.3

A poll of UK doctors found the majority opposed official introduction of both active voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Setting aside religious objections, their concerns were the impact these introductions might have on effective palliative care, how adequate safeguards would be introduced, and the growth of a non-medical “facilitating profession”.4 The latter concern hints at the fee-based services provided by private clinics, and it is assisted suicide at such facilities that create uncertainty for claims managers.

Assisted death – The facts

The UK National Health Service defines euthanasia as the act of deliberately ending a person’s life to relieve suffering, and uses the example of a doctor giving a fatal dose of muscle relaxants to a terminal cancer patient in order to end their life (see Table 1).5 The line dividing PAS as euthanasia from the more common and less controversial practice of palliative sedation is often blurred.

In the Netherlands, where it has been allowed, under strict conditions regulated by law since 2002, PAS is defined as the administering of lethal drugs by a doctor, on a patient’s explicit request with the intention of ending life. In 2010 reported cases totalled 3,136 or 2.3 per 1000 deaths.

Fewer than half of patient requests have been granted by doctors, which provides some reassurance that widespread abuse, or disproportionate use in vulnerable populations, has not occurred.6 The most common reasons to grant requests included no prospect of improvement, no further treatment options are available, or loss of dignity.

In Belgium, where active euthanasia has been legal for a decade, the share of reported deaths by euthanasia hit 7.9 per 1000 deaths in 2009. The underlying diseases were cancer (44% of cases), neurological degenerative disease (19%), cardiovascular disease (9%) and musculoskeletal disorders (6%). Other concomitant conditions included diabetes, blindness and lung disease. Depression was recorded in just 3% of cases, underlining the need for the subject to be of sound mind.

In contrast to the Belgian figures, the 300 NPAS deaths recorded in Switzerland during the same year represented 4.8 per 1000 deaths.7 NPAS represented 27% of all suicides by Swiss nationals. DIGNITAS, a Swiss-based company, provides members an “accompanied suicide” when they have a terminal illness, and or unendurable incapacitating disability and or unbearable, uncontrollable pain. To go through with the service, a member must be of sound mind and possess a minimum level of physical mobility sufficient to self-administer a fatal dose of Sodium Pentobarbital. The drug may be swallowed, taken through a gastric tube or administered intravenously. To meet legal requirements, the person must be able to undertake this final act without help. The cost of the service is not inconsequential. In addition to membership fees, the company requires payment of £7,500 up front to cover administrative costs, physician fees and funeral expenses – and without any guarantee of suicide occurring.8 DIGNITAS data from 1998 to 2012 reveals almost 1,500 people from more than 30 countries have exercised their right while 6,500 more from 80 countries are active members.9

The bigger picture – Rational suicide and claims

Data suggests that PAS occurs where life expectancy is short, measured in weeks.10 The implication is the impact is low in a death claims context. In contrast, people must decide when the time is right to act because they must have the physical ability to self-administer the fatal dose. In consequence, whilst terminally ill, these people are likely to be shortening their lives significantly.

However, the numbers of PAS and NPAS deaths are small when compared with those who make a rational decision to take their own life without any help. Globally, nearly one million people die from suicide each year.11 Depression is linked with the impact of poverty, debt, social problems, national austerity programmes and unemployment. People with risk factors for suicide because of mental illness are at greater risk of unemployment.12 Over half of people who die by suicide have had depressive symptoms at the time of death.

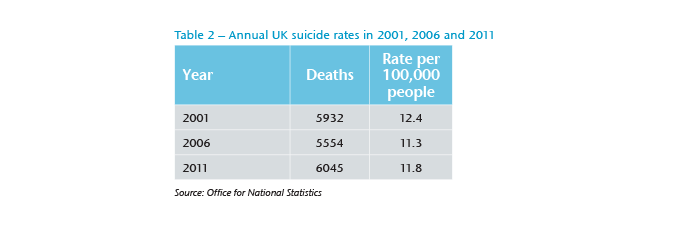

After the 2008 worldwide economic crisis, rates of suicide increased in Europe and America, particularly in men and in countries with higher levels of job loss.13 UK data, released in early 2013, revealed a significant rise in deaths from suicide over recent years following decades of rates trending downward (see Table 2). There is evidence linking the increase to the crisis.14

The trend has prompted a review of the use of suicide exclusion clauses, a common feature of insurance policies but not universally applied in all markets. Typically, the exclusion prevents a claim during the first policy year. The intention is to deter a person buying insurance with the premeditation of killing him or herself as an altruistic act for the financial benefit of the family or business. However, if a person who is healthy at the time of application later develops a psychotic depression that drives him or her to suicide, is this in any way different to dying from an unforeseen heart attack? With no relevant medical history, neither represents a legally capacitous choice to end life and, as both are illnesses in a very biological sense can excluding a mental cause be justified?

Wording an exclusion that can provide meaningful protection against possible anti-selection is also problematic, and perhaps destined to become more so, given the surge in PAS and NPAS. A wording should reflect acts of commission and omission; for example, refusing medication or sustenance to stay alive. Exclusions can be difficult to enforce in any but the most clear-cut circumstances where intent is obvious and agreed by a coroner.

It seems likely that claims will arise in future where suicide was the cause of death. Claims managers must be ready to work through the maze toward a decision that takes account of the individual circumstances of a case. Insurance companies must explore, and clearly articulate their stance, towards different ways and circumstances in which people take their own lives. Merely having a blanket approach to suicide across the board is no longer a defensible position given the complexities of the issue.