-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

Gen Re’s valuable insights and risk transfer solutions help clients improve their business results. With tailor-made reinsurance programs, clients can achieve their life & health risk management objectives.

UnderwritingTraining & Education

Publication

The Key Elements of Critical Illness Definitions for Mental Health Disorders

Publication

What Are We to Make of Cannabis Use in The Insured Population? Business School

Business School

Publication

Knife or Needle: Will the New Weight Loss Medication Replace Bariatric Surgery?

Publication

Weight Loss Medication of the Future – Will We Soon Live in a Society Without Obesity? Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Underwriting of Common Mental Health Disorders: Return-to-Work Strategies and the Role of Self-Efficacy

October 09, 2020

Dr. Chris Ball

English

There is a perception that mental health disorders are challenging to underwrite or will lead to potentially long-duration and complex claims. Reinforcing a cautious approach is the evidence that between 19% and 37% of employees with a sickness absence due to a Common Mental Disorder (CMD) will have a recurrent episode within two years of returning to work.1 Applicants for Disability Income (DI) cover are usually only asked brief medical questions. For some individuals, the wording makes it difficult to disclose their mental health problems effectively. This may put some off from trying to obtain DI cover for fear they will be unreasonably excluded from making mental health claims in future. It seems particularly unfair that a single disclosure of one mental health problem results in a blanket exclusion of potential claims for all others; e.g. an exclusion arising as a result of work-related problems invalidating a claim as a consequence of PTSD following a road traffic accident 5–10 years later. This paper explores what the return-to-work (RTW) literature tells us about people who make a robust return and are therefore likely to be low risk in the future, and those who require strategies to mitigate future risk.

Return-to-work strategies

Nigatu et al. reviewed the effectiveness of interventions for enhancing RTW for individuals with common mental illnesses. They concluded that the available interventions did little to improve RTW rates compared to control groups, but did reduce the time to RTW by an average of 13 days.2 While this improvement may not be clinically important, it may have economic implications. From a scientific point of view many of the studies were less than rigorous, but a more nuanced discussion of the results does suggest some pointers towards good practice.

Those who responded well to interventions had more senior therapists and integrated care, and the certification of fitness to work did not lie with the treating professionals. Finnes et al. broadly agreed with these conclusions. Reviewing psychological interventions alone, these authors could identify only small (if statistically significant) effects upon sickness absence compared to “management as usual”.3

Readiness to return to work – Self-efficacy

Most studies reviewed did not take into consideration a subject’s readiness to RTW. Readiness consists up of a combination of factors, such as quality of life, quality of work, work functioning and self-efficacy (SE). SE was defined in this context as the person’s belief in his or her ability to succeed in a specific behaviour.4

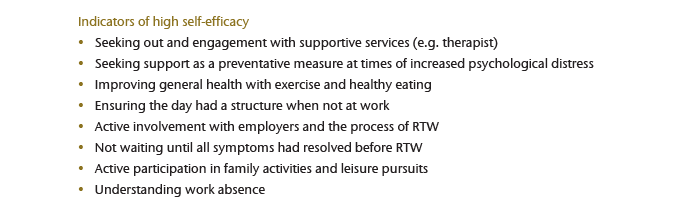

SE is demonstrated by a willingness to take steps to change one’s situation and expend energy in achieving this goal. The point was well made in a small study of work-focussed Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT), that identified workers with high levels of self-efficacy returning to work significantly faster than those who did not display this quality.5 Generally CBT without an overt work focus – probably the most frequently offered structured intervention through state and insurance sponsored health schemes – does little to improve time to return to work.6

While the response of elements of the work-place (feedback, structure, flexibility etc.) are all important in making a successful return to work, changes the individual makes also matter; e.g. more effective returns to work were achieved by taking better care of themselves by exercising or eating more healthily, establishing clear boundaries between work and leisure, and filling the leisure time in a constructive manner. For those who worked from home, making sure the day was structured, and dividing tasks and setting goals, were vital in maintaining productivity. Those who were able to ask for feedback and help found their RTW less difficult as confidence grew. Seeking support from outside work also appeared to be positive.7 The role of these personal factors has been linked to successful return to work after treatment, with those who expected to do well achieving a RTW at six-month follow up.8

Pulling these personal factors together within the concept of SE led to identifying SE as a key factor in enhancing work ability and RTW.9,10 SE has been criticised as merely reflective of the person’s symptoms and it has been shown that SE improves as symptoms improve. However, later work has also demonstrated that SE has a prognostic value over and above the influence of psychological symptoms.11

Defining self-efficacy

The original concept of SE was defined by Bandura as the belief in one’s abilities to complete a task.12

Bandura argued that expectations of personal efficacy determine whether someone will start new coping behaviours and how hard the individual will work to keep working on the behaviours when faced by obstacles or bad experiences. SE can be developed by engaging with activities that feel threatening but are actually quite safe, so that the person experiences mastery and has fewer defensive responses. Expectations grow from these achievements and learning from the behaviour of others. Persuasion may play a part in the process, as may physiological states, such as feeling stimulated.

To measure SE, the General Self-Efficacy Scale was developed and used extensively to explore this concept in several fields.13 Since then, a plethora of scales for specific situations have been developed, including the specific Return-to-Work – Self-Efficacy questionnaire that has been shown to be associated with RTW even after long periods of sick leave.14

The RTW-SE Scale contains 11 items that are categorised on a six-point scale. A mean score of the 11 items is used to complete the scale score.

There is scope at underwriting for identifying those with high SE scores who are likely to respond well after any relapse of a common mental disorder and who are likely to avoid a prolonged absence from work. However, for the many insurers formally measuring this trait, this identification might prove difficult. But it may be possible to form a view from an application process that explores responses to previous episodes of sickness absence looking for indicators of high SE.

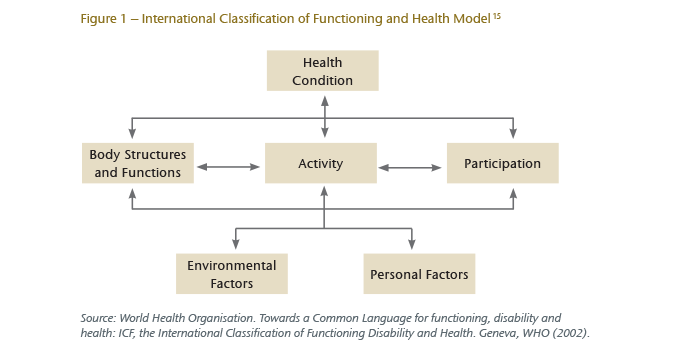

The WHO has developed a model that relates health, functioning and disability, and it understands that medical factors are not the only issue in the functioning of an individual. Return-to-work is not only determined by recovery of symptoms (as is usually assumed) but also determined by personal and environmental conditions.

Beyond broad categories of occupation, many job-related factors cannot be considered in the underwriting process, particularly as people change their jobs with greater frequency these days. A myriad of factors – such as how good a supervisor is at supporting the person back into work, co-worker support, the physical environment – are likely to change over time and be different in different work settings. To some extent, a disconnect also exists between the expressed symptomatology and returning to work, which means that interventions solely related to symptoms have been shown to have little impact on sickness absence.16

The call for a biopsychosocial approach to underwriting, taking into account not only the medical but also the social and psychological circumstances of an individual, has become increasingly explicit.17 Exploring the manner in which individuals have responded to previous bouts of sickness-related absence, in a systematic way and with a clear conceptual basis, represents one potential approach towards underwriters being able to take into account more factors – medical, social and psychological. Any research that explores this possibility must include a robust set of questions and not merely have face validity for the insurer. SE represents one such possibility because the understanding of SE scores on returning to work have been well documented over a considerable time period.