-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves?

Publication

Pedestrian Fatalities Are on the Rise. How Do We Fix That? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

The Effects of Heatwaves – A Look at Heat-related Mortality in Europe and South Korea

Publication

The Key Elements of Critical Illness Definitions for Mental Health Disorders

Publication

An Overview of Mitral Regurgitation Heart Valve Disorder – and Underwriting Considerations

Publication

Body Mass Index as a Predictor of Cardiovascular Health Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

The Role of Resilience and Self-Efficacy in Mental Health Claims Management

July 29, 2021

Mary Enslin

English

Français

For many years, there has been speculation about the emergence of an “epidemic” of mental health disorders (MHDs). COVID‑19 has intensified this speculation further, with many comments in the press and on social media predicting that MHDs represent a “hidden third wave” of the coronavirus pandemic.

Gen Re has previously investigated whether there is evidence to support this supposed epidemic of MHDs and found that any increase in the prevalence of common MHDs is modest and likely due to population changes, such as ageing populations and growth. Nevertheless, despite unprecedented levels of awareness, support and advice relating to self-care and prevention, MHDs remain a significant (top three) cause of Disability claims.

Furthermore, studies have noted very little correlation between the severity of the reported symptoms and the functional outcomes and prognosis (e.g. returning to work).1,2 In fact, they found that a focus on symptoms instead of resources can reinforce illness identity and non‑work identity in patients, which in turn can have a negative effect on the return-to-work process.3

Claims professionals should avoid focusing on symptoms alone and consider a more holistic approach to the assessment of MHD claims. This article explores the Bio-Psycho-Social model as an alternative to the traditional symptoms-focused approach to claims, as well as looking at the role of resilience and self-efficacy in claims management and return to work.

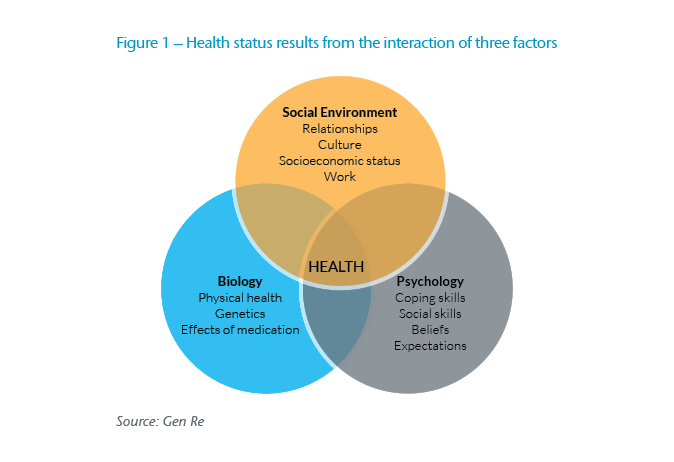

The Bio-Psycho-Social (BPS) model

The Bio-Psycho-Social (BPS) model presents a holistic means of understanding the precipitating and perpetuating factors that may contribute to an individual’s health. The model proposes that an individual’s health and well-being are not determined solely by their biological characteristics. Rather, as shown in Figure 1, health status results from the interaction between biological (physical health, genetics, medication effects), psychological (coping skills, social skills, beliefs and expectations, mental health) and socio-environmental factors (relationships, culture, socioeconomic status, work).4

The BPS model can be a useful tool for claim examiners wishing to deepen their understanding of the various medical and non-medical factors contributing to a workplace absence. For example, an individual may receive excellent medical care and engage well with prescribed treatment, but if there is serious, unresolved conflict in the workplace, it may present a significant barrier to recovery and return to work.

Despite our understanding that claims resulting from MHDs are complex and multi-factorial, in many instances, the evidence-gathering stage of claims assessment may lean towards the biological (or medical) aspects of the claim. Think about the content and design of claims forms: Is there one standard form for all claims or are forms customized, depending on whether the claim is due to a medical condition or MHD? Does the claims form or evidence gathering process focus on symptoms and treatment, or does it include exploration of the psychological and socio-environmental factors mentioned above?

Many of these factors are abstract and it can be difficult to know the right questions to ask. As a starting point, therefore, consider exploring the possible role of resilience and self-efficacy in the claim.

Defining resilience and self-efficacy

Resilience and self-efficacy have become buzz words in mental health. Although they are related and interdependent concepts, they also have subtle differences. Resilience is the ability to recover readily from adversity. The term comes from the Latin word resilire, which means “to spring back”.5

An individual’s level of resilience fluctuates over time and is influenced by a number of factors, including genetics, personality, childhood experiences, personal history, environment, and others. The most important of these appears to be childhood experiences.6 Thus, while understanding resilience can help predict a claimant’s prognosis, there may be little that another can do to influence it.

Psychologist Albert Bandura defined self-efficacy as people's beliefs in their capabilities to exercise control over their own functioning and over events that affect their lives.7 One's sense of self-efficacy provides the foundation for motivation, well-being, and personal accomplishment.

Individuals with high levels of perceived self-efficacy trust their own abilities in the face of adversity, tend to conceptualize problems as challenges rather than as threats or uncontrollable situations, experience less negative emotional arousal in demanding tasks, think in self-enhancing ways, motivate themselves, and show perseverance when confronted with difficult situations. In contrast, people with low perceived self-efficacy tend to experience self-doubt and anxiety when they encounter environmental demands. They perceive demanding tasks to be threatening, avoid difficult situations, tend to cope less functionally with stressors, and are more likely to think in self-debilitating ways.8

When looking specifically at the impact on mental health, studies found increased levels of self-efficacy, combined with problem-oriented coping strategies and an internal locus of control, improve mental health. Conversely, decreased self-efficacy, emotion-oriented coping strategies and an external locus of control lead to decreased mental health.9,10

Individuals using positive emotions to find meaning in negative circumstances are more resilient. These individuals have more effective coping mechanisms and can bounce back from negative events effectively, whereas others cannot bounce back from such events. To put this in an impairment context, workers with high self-efficacy are more likely to return to work following absence,11 and typically return to work significantly faster than those with less self-efficacy.13

Even when a MHD is not the primary cause of claim, an individual’s resilience and self-efficacy play a role in their recovery and attitude towards returning to work. In fact, studies show that self-efficacy is a robust predictor of various health outcomes and behaviours, including physical activity, healthy eating, smoking cessation, alcohol abstinence, and health behaviour change among cancer and cardiac patients.14 Some studies even found that when self-efficacy was measured pre-surgery, it could predict the recovery of cardiac patients over a half-year period.15

Thus, we can see self-efficacy's importance in predicting of resilience, general health status, mental health status, and return to work. Unlike resilience, which is often described as a personality trait, self-efficacy is a skill that can be measured and learnt. Furthermore, studies have shown that improving self-efficacy can reduce levels of depression and other MHDs.16

There is therefore great potential to incorporate understanding and utilization of self-efficacy and the BPS model when managing claims. Gen Re has already examined some potential applications in underwriting, and below we explore their application in the claims process.

Measuring self-efficacy

There are various tools and scales that have been developed to measure self-efficacy. Below we describe three scales that are useful for evaluating self-efficacy in general and also in the return to work context specifically.

The General Self-Efficacy (GSE) Scale was developed to predict an individual’s ability to cope with daily stress and the period following experiencing various kinds of stressful life events. It consists of 10 items with responses on a four-point scale, resulting in a score range of 10 to 40. The results reflect an individual's current perceived self-efficacy and the scale can be reapplied over time to assess changes in quality of life. Higher scores indicate higher perceived general self-efficacy; lower scores indicate lower perceived general self‑efficacy. Perceived self-efficacy is related to subsequent behavior and, therefore, is relevant for clinical practice and behavior change.17

Researchers also developed a specific Return-to-Work Self-Efficacy Scale (RTW‑SE) for workers with MHDs, which proves to be a robust predictor of full return to work post-treatment.18 It asks individuals to respond to 11 statements about their jobs, imagining returning to work full time tomorrow (in their present emotional state/state of mind). Questions included in the scale are similar to those in the General Self efficacy scale with a greater focus on work aspects. For example, “I will be able to set my personal boundaries at work”, “I will be able to cope with work pressure”, and “I can motivate myself to perform my job. Responses vary from “totally disagree” to ‘‘totally agree’’ on a six‑point scale. Higher scores are associated with a higher likelihood of returning to work and vice versa.

Lastly, the Return-to-Work Obstacles and Self-Efficacy Scale (ROSES) was developed to measure the BPS obstacles that impede return to work of people with common mental health or musculoskeletal disorders, and to assess the perceived self-efficacy to overcome these potential obstacles. The scale consists of 46 statements covering 10 dimensions which categorize the statements into themes such as “Fear of relapse”, “Job demands”, “Difficult relationships with co-workers”, and “Loss of motivation to return to work”. The scores within each dimension predict return to work and identify which specific dimensions may need additional intervention and support.19

Potential applications for claims management

Effective claims management should not focus solely on medical aspects (symptoms, treatment). Rather, a strong understanding of BPS aspects is required to identify obstacles and consider the self-efficacy needed to overcome them. A deeper understanding of the role of self-efficacy will greatly assist with this, and there are also specific practical suggestions you can consider incorporating into your claims process, depending on what is permitted in your market.

1. Providing Adequate Support and Interventions

All claims should be evaluated on their own unique set of circumstances. Some may require more intensive support than others. Depending on the cause and specific BPS factors within a claim, some individuals may recover independently at a relatively predictable pace while others may require more frequent interventions before a return to work can be achieved. Awareness of self-efficacy levels may help you identify claims where enhanced self-management support is needed. For example, an individual with low self-efficacy may benefit from more frequent communication and education on how to develop his or her self-efficacy (see 3. below). As a reinsurer, sharing this knowledge with our ceding companies equips them to, in turn, assist their customers.

2. Gathering Evidence

Since each claim is unique, the information required to conduct a proper assessment may differ. How and what information is requested can be as important as assessing what is received. When developing or modifying claims forms, consider including questions to help identify the BPS obstacles that exist and the degree of self-efficacy. If you make use of tele-assessment, you may want to consider using communication techniques like motivational interviewing.20

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing is a collaborative, goal-oriented style of communication with particular attention to the language of change. It is designed to strengthen personal motivation for, and commitment to, a specific goal by eliciting and exploring the person’s own reasons for change within an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion.

The claimant’s specific treatment methods and goals can also have a significant impact on the prognosis. For example, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is generally accepted as a gold-standard, evidence-based mental health treatment approach to alleviate symptoms of anxiety and depression. However, one study found that without an overt work focus, CBT does little to improve time to return to work.21

Another recommendation is to ensure treatment plans and regimens include:

- Adequate details on the treatment goals, objectives and methods.

- Goals aimed at return to work, addressing any BPS obstacles, and identifying opportunities to increase self-efficacy. If they are absent it is appropriate to inquire why.

- Education for the insured on the benefits and importance of proper self-care (see point 3(d) below).

3. Developing Self-Efficacy Skills

There are several resources that provide practical advice on how to improve one’s self-efficacy, and the literature typically identifies four main sources which influence this:22,23

In addition to the above, there are also several self-guided mobile phone and web-based psychotherapeutic interventions that may improve self-efficacy and encourage self‑care.25

Conclusion

Claims caused, influenced, or perpetuated by MHDs can be complex to manage; the topics discussed in this article are just one piece of the puzzle. However, by using the BPS approach to understand all potential barriers to returning to work and encouraging the self-efficacy required to overcome these barriers, claims professionals may play a positive role in supporting the recovery and return to work of claimants. This represents a win-win for both claimants and insurers.

July is International Self-Care Month. Many useful resources can be found on the World Health Organization and International Self-Care Foundation websites respectively.

This article is part of a series looking at different aspects of mental health through an insurance lens. Next month we’ll be taking a deeper dive into strategies for communication and sharing best practices on evidence gathering in mental health claims.